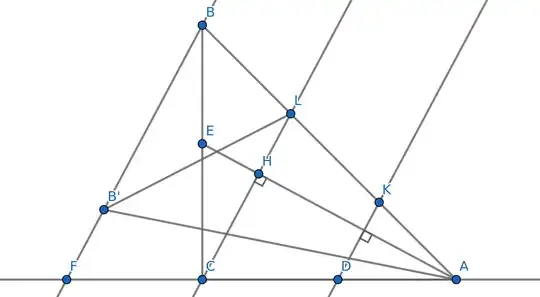

On the sides $CA$ and $CB$ of an isosceles right-angled triangle $ABC$, points $D$ and $E$ are chosen such that $|CD|=|CE|$. The perpendiculars from $D$ and $C$ on $AE$ intersect the hypotenuse $AB$ in $K$ and $L$ respectively. Prove that $|KL|=|LB|$.

Proposed by Victors Linis, University of Ottawa.

Crux Mathematicorum Vol. 1, No. 4, June, 1975

I want a solution via vectors and I'll explain why in the end of the question, tl;dr.

The question consists of:

- the basic things we can do with vectors,

- how did I come to a regular geometric solution,

- regular geometric solution,

- motivation for vectors approach.

To give more explicit context, I'll explain the basic things we can do with vectors to approach real geometry problems.

- We can add or subtract vectors, e.g. $\overrightarrow{AB}+\overrightarrow{BC}=\overrightarrow{AC}$.

- We can scale a vector by a coefficient (say $k$) so if $A,B,C$ lie on the same line and $k=\frac{AC}{AB}$ then $\overrightarrow{AC}=k\overrightarrow{AB}$.

- In particular, 1. and 2. follows that if $X$ is on $AB$, such that $\frac{AX}{XB}=\frac{t}{1-t}$ then $\overrightarrow{OX}$ $=\overrightarrow{OA}+\overrightarrow{AX}$ $= \overrightarrow{OA}+t\,\overrightarrow{AB}$ $= \overrightarrow{OA}+t(\overrightarrow{OB}-\overrightarrow{OA})$$= t\,\overrightarrow{OB}+(1-t)\,\overrightarrow{OA}$.

- If some vectors form a basis, then every vector has unique representation as a linear combination of basis vectors with coefficients called "coordinates" (e.g. $\overrightarrow{i},\,\overrightarrow{j},\,\overrightarrow{k}$ is a classical basis for 3d Cartesian coordinates).

Knowing only 1.-4. some problems like this (not in a way attention drawing) may be solved when a convinient basis is chosen, and even Ceva's_theorem, Menelaus's theorem, Thales' theorem can be proven, almost in an algebraic way. I'd call such "linear vector problems". But we know also - Scalar (dot) product. By definition

$\cos\angle BAC=\frac{\overrightarrow{BA}\cdot\overrightarrow{BC}}{

|\overrightarrow{BA}|\cdot|\overrightarrow{BC}|}$, or, alternatively, $(\overrightarrow{BA}\cdot\overrightarrow{BC})=BA\cdot BC\cdot \cos\angle BAC$. This implies such things like $(\overrightarrow{BA}\cdot \overrightarrow{BA})=(\overrightarrow{BA})^2=|\overrightarrow{BA}|^2=BA^2$ and $(\overrightarrow{BA}\cdot\overrightarrow{BC})=0\Leftrightarrow BA\perp BC$ unless $BA$ or $BC$ equals to zero. All distributive laws holds for addition/subtraction related to scalar or/and dot product.

With 1.-5. such things like cosine rule, Heron's formula, Ptolemy's_theorem can be proven and I believe the problem above can be solved too.) We also know (though it's usage mostly limited by 3d Cartesian space) - Cross product

Having these tools, we can approach problems, where all conditions given and things to be proven/found are: parallelity, perpendicularity, fixed angles, intersection, intersection at a ratio (and maybe some others). But apparently we can't deal with circles, addition/subtraction of angles and many other things. But boiling a geometric problem down to algebra can be useful when no other ways seen. Other approaches are complex numbers or Cartesian coordinates, but vectors are unfairly less popular/known. I'd say, many vectors excercises are constructed just to train using vectors, instead of showing how real geometrical problems may be solved in an algebraic way.

Arriving at regular geometrical solution

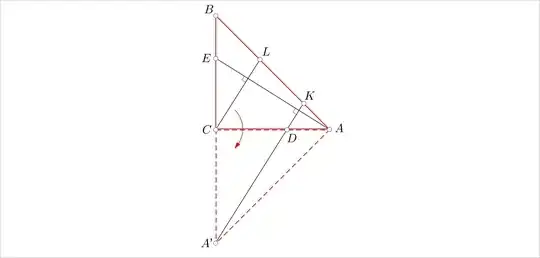

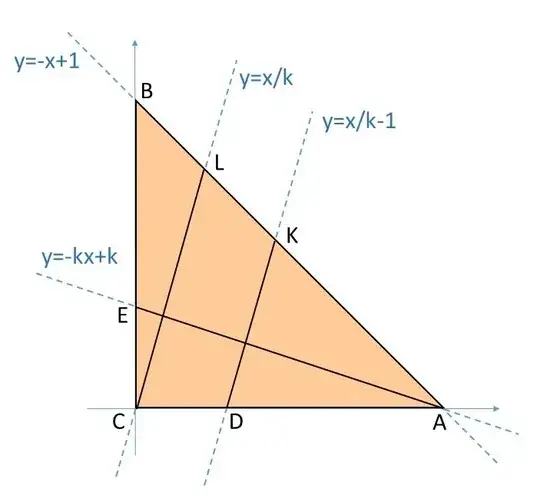

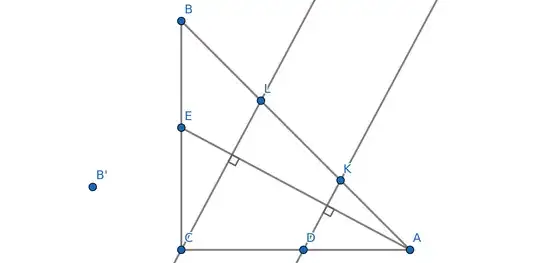

I made the figure above in geogebra and started moving free point $D$ back and forth and see how the things change and I noted that somewhat asymmethrical that we have $3$ points on $AB$ and only two on $AE$, I wanted inverse-image of $B$ to be present to. To construct it, I mirrored $B$ relative to $AE$ into $B'$.

By moving $D$ I noted that $BB'||CL||DK$ (and indeed, they all are perpendicular to $AE$) and that reminded me of Thales' theorem -- if we have say $F=BB'\cap AC$

then it would suffice to show that $DC=CF$ and use Thales' theorem. By "method of gazely staring" I found that $\triangle CFB\sim \triangle HEC$, but it's obvious that $\triangle HEC\sim\triangle CEA$, but $CA=CB$ and thus $CE=CF$, but it's given that $CD=CE$, which completes the proof.

Geometrical solution, refined

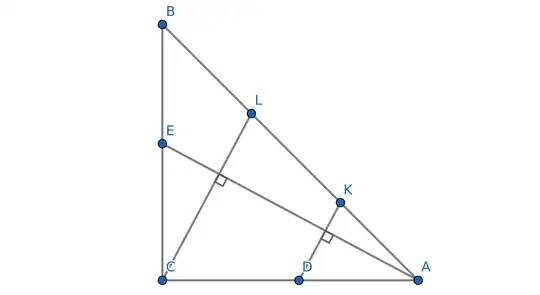

We take $F$ on the line $AC$ such that $BF||CL$.

$\angle FBC=\angle ECH$, where $H=CL\cap EA$.

From right-angled $\triangle ECH$: $\angle ECH=90^\circ -\angle CEH$,

but from right-angled $\triangle ECA$: $\angle CAE=90^\circ -\angle CEH$

thus $\angle FBC=\angle ECH=\angle EAC$

hence $\triangle FBC$ and $\triangle EAC$ are congruent by ASA

that follows $CF=CE$,

but it's given that $CD=CE$ thus $CF=CD$

and using Thales' theorem on lines $AB$, $AC$ intersected by $BF \parallel CL \parallel DK$ we obtain $BL=LK$, QED.

But imagine I were at a contest without being able to use geogebra and move the point $D$ and to want to construct $BB'$, then arriving at this solution with such additional constructions is highly doubtful. While vectors approach is pretty straightforward: algebraically express what's given and what's needed, solve algebraical problem, usually a linear equations system. That's why I want vectors solution. Other algebraical solutions, like Cartesian coordinates, complex coordinates or even something like barycentric coordinates are welcome as well.

Thanks for reading this through out.)