A college math Professor told me that equations for circumference depend on which metric is used. For a plane circle and an equator on a sphere, one gets the same result after integrating the metric, for a particular metric, for both circles. Of course one can’t use a non-flat metric on a plane circle. In addition, whether the metric is straight or curved doesn’t affect the answer, he said, because it is still essentially straight. If one could zoom in that would be apparent (of course one can’t see at the infinitesimal level). He meant a Euclidean metric on the sphere works well enough, as good as the Riemannian netric defined by the inner product of tangent vectors. Hence great circle circumference is essentially still $2 pi R$. Using the Euclidean metric one would integrate it on segments of a circle on 2D charts, then add up the segments to obtain an accurate, entire circumference.

My post addresses the issue from the point of view of trigonometry and from the view of the metric. I reference two stack posts below, neither of which appears unsatisfactory to me in its explanation. I do agree that spherical circumference is less than $2 pi r$.

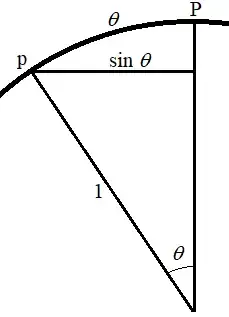

The post Circumference of a circle in hyperbolic space indicates (in answer #2) that a circle in the hyperbolic plane, as well as one on a sphere, has a circumference different from that in the 2D plane. However, it uses arc length ‘l’ of a geodesic circle, from pole to circle’s edge. I don’t know what the arc lying on the surface of the sphere has to do with circumference. The answer in the post uses the equation $s = rϴ$ so $‘l’ = ϴ$ for the unit sphere. Saying $C = 2 pi sin(l)$ where l equals ϴ isn’t really any different from saying $C = 2 x pi x radius$ if $radius = sin(ϴ)$ for a unit sphere. I don’t see how this basic equation differs from the circle in the plane.The post says circumference on the sphere is less than $2 pi ‘l’$ but the radius segment lying in the surface is not relevant to circumference (there’s no comparison to ‘l’ for a plane circle) except for the fact that it equals ϴ if $r = 1$. This post also omits any notion of curvature and just uses trigonometry and the metric $ds^2 = r^2dϴ^2$, a Euclidean one if I’m not mistaken. A main purpose of my post is to establish if this same metric is even valid on a sphere.

The post A casual definition of Hyperbolic Space states the conclusion as a straight fact (below the MC Escher diagram) without using much math, except for the first discussion of tiling for the hyperbolic plane.

Because the two posts above don’t establish the comparison well and do not contain derivations that involve curvature or any reference to a non-flat metric, I rephrased my question below:

The stack post great circle distance derives a metric in terms of x, y and r, based on the squared norm. This can be converted to r, ϴ, psi. What is the equivalent metric in spherical coordinates? Alternatively, what metric does one obtain from using the norm squared with spherical coordinates? Is the result of integrating this spherical coordinate metric for a great circle exactly equal to $2 pi R$ (R = spherical radius) or is it different? Is the metric $ds^2 = r^2dϴ^2$ not valid on a sphere?

Is it true that the intersection of a sphere at the equator with a plane produces a circle that is different from the great circle? I.e.: it lies on a different manifold and the points of the two circles do not coincide exactly. I’m not saying they’re topologically different, I’m saying geometrically. Integer solutions of $R^2 = x^2 + y^2 + z^2$ ($z = 0$) would lie on both circles, as would some other solutions. But one has positive Gaussian curvature and the other has $K = 0$. Would a map from the great circle to the plane circle deform the original circle? Although $z = 0$ in this case, the inclusion of z does contribute to the norm squared metric that differentiates the sphere from a plane circle. If this metric can not even exist for the plane circle, can one say they are not the same circle (not all points coincide)?