I'm a physics student. I'm currently taking a complex analysis course and I'm struggling to understand how the determination of a function is given on its branch cut. Since it is hard for me to even formulate what I don't understand, I will try to lay out my reasoning using an exercise I was given, and asking questions along. I have this integral:

$$ I = \int_0^{+\infty} \frac{dx}{\sqrt[3]{x} (x + 1)} $$

Now I can bind the integral over the real number field to one on the complex field, considering the complex function:

$$f(z) = \frac{1}{\sqrt[3]{z} (z+1)}$$

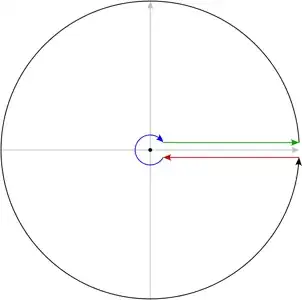

As I've understood, since $\sqrt[3]{z}$ has a branch point in $z_0 = 0$ (and $z_1 = \infty$) it is necessary to place a branch cut on the complex plane. Here it is the first question. Can I place the branch cut wherever I want, as long as it connects the two singular $z_0$ and $z_1$? Up until now, I assumed I can. I choose to place the branch cut on the real axis in $[0, +\infty]$. The integration contour is the following:

I will refer to the whole curve as $\Gamma$, to the black arc as $\phi_R: z = Re^{i\theta}$ and to the blue part as $\gamma_\epsilon: z = \epsilon e^{i\theta}$:

$$ \oint_\Gamma f(z)dz = \int_{\phi_R} f(z)dz + \int_R^\epsilon f(z)dz + \int_{\gamma_\epsilon} f(z)dz + \int_\epsilon^R f(z) dz$$

Now, I can take a limit:

$$ \lim_{\begin{aligned} R &\to +\infty \\ \epsilon &\to 0 \end{aligned}}\oint_\Gamma f(z)dz = \lim_{R \to +\infty} \int_{\phi_R} f(z)dz + \lim_{\epsilon \to 0} + \int_{\gamma_\epsilon} f(z)dz + \lim_{\begin{aligned} R &\to +\infty \\ \epsilon &\to 0 \end{aligned}} \left(\int_R^\epsilon f(z)dz + \int_\epsilon^R f(z)dz \right) $$

$$ \lim_{\begin{aligned} R &\to +\infty \\ \epsilon &\to 0 \end{aligned}}\oint_\Gamma f(z)dz = \int_{+\infty}^0 f(x^+)dx + \int_0^{+\infty} f(x^-)dx = \int_0^{+\infty} (-f(x^+) + f(x^-)) dx = 2 \pi i \sum_{i \: s.t. \: z_i \in \mathring{\Gamma}} \mathrm{Res}[f(z), z_i]$$

where, with $f(x^+)$ and $f(x^-)$ I am referring to the value of the function over and below the cut of the function. It is necessary to determine the form of the function over and under the cut.

Now the core of my question. How do I provide the determination of the function? The thing is that I cannot figure out what comes first and what follows when one has to provide the determination of the function. Now as I understand I need to choose a Riemann sheet to calcuate the integral on. What does it specifically mean to choose on a specific Riemann sheet? Now I thought that the function over and under the branch cut has two different forms, because when crossing the cut one also change Riemann sheet. However sometimes it seems as if, in the example exercises, two forms of the function are given, one over and one under the cut. I've come up with two different procedures to try to give some motivation to example exercises:

reasoning 1) $$ \sqrt[3]{z} = \left( \rho e^{i\left( \theta + 2k \pi \right)} \right)^{\frac{1}{3}} = \sqrt[3]{\rho} e^{i \left( \frac{\theta}{3} + \frac{2}{3} k \pi \right)} = \begin{cases} \sqrt[3]{\rho} e^{i \frac{\theta}{3}} &\longrightarrow \textbf{first form} \\ \sqrt[3]{\rho} e^{i(\frac{\theta}{3} + \frac{2}{3}\pi)} &\longrightarrow \textbf{second form} \\ \sqrt[3]{\rho} e^{i(\frac{\theta}{3} + \frac{4}{3}\pi)} &\longrightarrow \textbf{third form} \end{cases}$$

\begin{align} z = x^+ && 0 < x && \Longrightarrow && &\text{we are over the cut} && \Longrightarrow && \theta = 0 && \Longrightarrow && \begin{cases} \sqrt[3]{x} \\ \sqrt[3]{x} e^{\frac{2}{3}\pi i} \\ \sqrt[3]{x} e^{\frac{4}{3}\pi i}\end{cases} && \xrightarrow{\textbf{I choose the first form}} && \sqrt[3]{z} = \sqrt[3]{x}\\ z = x^- && 0 < x && \Longrightarrow && &\text{we are under the cut} && \Longrightarrow && \theta = 2\pi && \Longrightarrow && \begin{cases} \sqrt[3]{x} e^{\frac{2}{3}\pi i} \\ \sqrt[3]{x} e^{\frac{4}{3}\pi i} \\ \sqrt[3]{x} \end{cases} && \xrightarrow{\textbf{I choose the second form}} && \sqrt[3]{z} = \sqrt[3]{x} e^{\frac{4}{3} \pi i} \end{align}

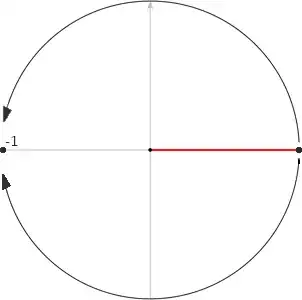

Note the implication arrow, as one of my core doubts is what comes first in the reasoning. Now the question related to this kind of reasoning: is it necessary to take the angle over and under the cut to be out of phase of $2 \pi$ or is it possible to choose both angle to be $0$ or $2\pi$? in fact, if I place a point on the cut, exactly on the cut, I cannot determine wheter I have approached the cut from over or under, therefore the only way of telling is using the phase, nevertheless, this kind of reasoning doesn't satisfy me. as, in other examples, I saw that, in order to determine the value of the function $\sqrt[3]{z}$ outside the cut, for instance in $-1$, one can take a path connecting a point on the cut to $z = -1$. If the path is taken to begin over the cut, then

$$ \theta^{(0)} = 0 \to \theta = \pi \xrightarrow[\text{as it is the one chosen over the cut}]{\text{plug it in into the first form}} \sqrt[3]{z} = \sqrt[3]{\rho} e^{i\frac{\theta}{3}} = \sqrt[3]{1} e^{i0} = 1$$

if the path is taken to begin under the cut, then

$$ \theta^{(0)} = 0 \to \theta = -\pi \xrightarrow[\text{as it is the one chosen under the cut}]{\text{plug it in into the second form}} \sqrt[3]{z} = \sqrt[3]{\rho} e^{i(\frac{\theta}{3} + \frac{2}{3}\pi)} = \sqrt[3]{1} e^{i\frac{\pi}{3}} = e^{i\frac{\pi}{3}}$$

How is it possible to for $\sqrt[3]{z}$ to have different values in $-1$ if it is monodrome everywhere but on the cut? Had have I followed the previous remark the question still holds: adding $2\pi$ to the phase with which one starts over the cut, the value in $-1$ continues to be different:

$$ \theta^{(0)} = 0 \to \theta = 2\pi \xrightarrow[\text{as it is the one chosen under the cut}]{\text{plug it in into the second form}} \sqrt[3]{z} = \sqrt[3]{\rho} e^{i(\frac{\theta}{3} + \frac{2}{3}\pi)} = \sqrt[3]{1} e^{i\frac{4}{3}\pi} = e^{i\frac{4\pi}{3}}$$

reasoning 2)

$$ \sqrt[3]{z} = \left( \rho e^{i\left( \theta + 2k \pi \right)} \right)^{\frac{1}{3}} = \sqrt[3]{\rho} e^{i \left( \frac{\theta}{3} + \frac{2}{3} k \pi \right)} = \begin{cases} \sqrt[3]{\rho} e^{i \frac{\theta}{3}} &\longrightarrow \textbf{first form} \\ \sqrt[3]{\rho} e^{i(\frac{\theta}{3} + \frac{2}{3}\pi)} &\longrightarrow \textbf{second form} \\ \sqrt[3]{\rho} e^{i(\frac{\theta}{3} + \frac{4}{3}\pi)} &\longrightarrow \textbf{third form} \end{cases}$$

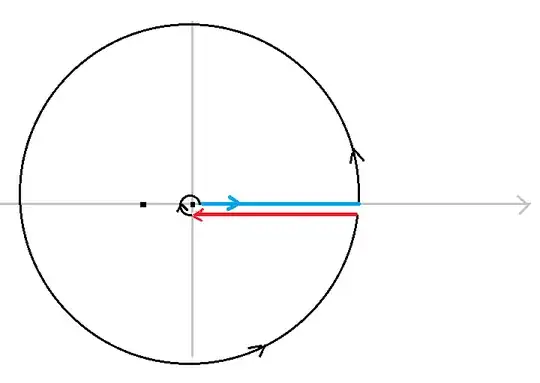

I choose the first form $\sqrt[3]{z} = \sqrt[3]{\rho} e^{i\frac{\theta}{3}} \Longrightarrow$ \begin{align} z &= x^+ && 0 < x && \Longrightarrow && \text{over the cut} && \Longrightarrow && \theta = 0 && \Longrightarrow && \sqrt[3]{z} = \sqrt[3]{\rho} \\ z &= x^+ && 0 < x && \Longrightarrow && \text{under the cut} && \Longrightarrow && \theta = 2\pi && \Longrightarrow && \sqrt[3]{z} = \sqrt[3]{\rho} e^{\frac{2}{3} \pi i} \end{align}

Again, note the implication arrows. In this case the the phase over and under the cut must be out of phase of $2\pi$, I think, otherwise, the function would have the same form over and under the cut, which is not possible. The rest of the exercise is not important to me right now.

Summing up all the questions:

- Can I place the branch cut wherever I want, as long as it connects the two singular points?

- In general, what does it mean to choose a certain Riemann sheet?

- How does the reasoning to provide the function form and determination over and under the cut work?

- do the angles over and under the cut need to be out of phase of a factor of $2 \pi$?

- do I choose two forms of the function or just one?

- Why doesn't the function have the same value outside the cut when calculating it using different paths?

I've been trying to understand this for the most part of the course, but still reached no conclusion. So, thanks a lot in advance for your help!