I believe your confusion stems from not understanding how exponentials, logarithms, and arguments come into play here. In this answer, we'll refresh ourselves with some basics and dive into the main problem after.

PRIMER

The definition of complex exponentiation $z^\alpha$, where $\alpha \in \mathbb{C}$, is

$$

z^\alpha = \exp(\alpha \log z)\,.

$$

In turn, the definition of $\log z$ is a multivalued function defined as

$$

\log z = \ln |z| + i \arg z\,,

$$

where $\arg z$ is the argument of a complex number $z$, defined as the angle between the positive real axis and the line joining the origin. To avoid multivalued functions for $z^\alpha$, we choose an interval for $\arg z$. We may specify some initial angle $\theta_0 \in \mathbb{R}$ and make $\arg z$ live in the interval $(\theta_0, \theta_0 + 2\pi)$.

Knowing these, we have the following equality:

$$

z^\alpha = \exp(\alpha \log z) = \exp(\alpha \ln|z| + i \alpha \arg z) = |z|^\alpha \exp(i \alpha \arg z)\,. \tag{1}

$$

See here for more details.

For example, the following equality holds when $a > 0$ and $\arg(-a) \in (-\pi,\pi]$:

$$

\sqrt{-a} = i \sqrt{a}\,. \tag{2}

$$

The equalities $(1)$ and $(2)$ will be useful later.

EXERCISE

Foreword: In the following proof, I will assume we are dealing with the principal branch of the logarithm. The proof could work for the branch cuts described in the comments above, but I didn't check. Also, I'll assume the contour travels clockwise. Even though these assumptions aren't stated in the original post, I hope this proof will be enough to answer your question.

Define the holomorphic function $f: \mathbb{C} \setminus [1,2] \to \mathbb{C}$ where $\displaystyle f(z) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{z-1}\sqrt{z-2}}$. Here, we further define $\operatorname{Arg}(z-1),\operatorname{Arg}(z-2) \in (-\pi,\pi]$. Let $\mathcal{C}$ be a circle traveling clockwise that contains the branch points $z=1$ and $z=2$. We will prove

$$

2\int_1^2 f(x)dx = \oint_{\mathcal{C}}f(z)dz\,.

$$

PROOF

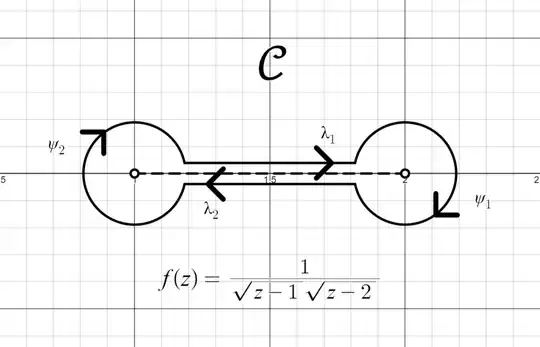

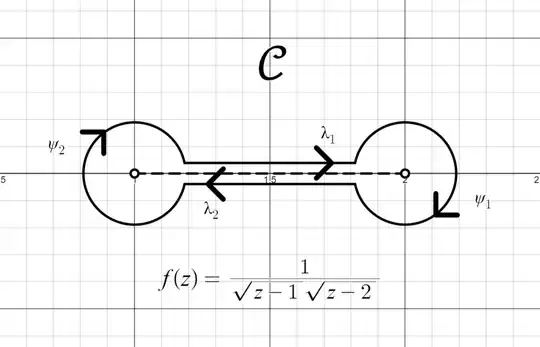

We deform $\mathcal{C}$ using the principle of contour deformation from a circle to the shape of a dumbbell/dogbone/sausage depicted below.

$$

\text{Figure 1: Dumbbell Contour $\mathcal{C}$ Traveling Clockwise}

$$

Let $0 < \delta < r < \frac{1}{2}$ where $\delta$ is the distance between the real axis and either $\lambda_1$ or $\lambda_2$ and $r$ is the radius of $\psi_1$ and $\psi_2$. Let $\epsilon = \sqrt{r^2 - \delta^2}$. Using geometry, we can formally express $\mathcal{C}$ as the union of the four contours:

$$

\begin{align}

\lambda_1 &= \left\{t+i\delta : t \in [1+\epsilon, 2-\epsilon]\right\} \\

\psi_1 &= \left\{2+re^{-it}: t \in \left[-\pi + \arctan\left(\frac{\delta}{\epsilon}\right), \pi + \arctan\left(\frac{\delta}{\epsilon}\right)\right]\right\} \\

\lambda_2 &= \left\{-t-i\delta: t \in [\epsilon-2,-1-\epsilon]\right\} \\

\psi_2 &= \left\{1+re^{-it}: t \in \left[\arctan\left(\frac{\delta}{\epsilon} \right), 2\pi - \arctan\left(\frac{\delta}{\epsilon} \right)\right]\right\}\,.

\end{align}

$$

In a similar example here, I used a similar process to construct a contour using geometry. If you want to verify that these constructions don't have any typos, I put them here in Desmos.

We integrate over the four contours and get

$$

\oint_{\mathcal{C}}f(z)dz = \int_{\lambda_1}f(z)dz + \int_{\psi_1}f(z)dz + \int_{\lambda_2}f(z)dz + \int_{\psi_2}f(z)dz\,. \\

$$

Applying the iterated limits $\displaystyle \lim_{r \to 0^+}\lim_{\delta \to 0^+}$ on both sides of the equality, we get

$$

\lim_{r \to 0^+}\lim_{\delta \to 0^+}\oint_{\mathcal{C}}f(z)dz = \lim_{r \to 0^+}\lim_{\delta \to 0^+}\left(\int_{\lambda_1}f(z)dz + \int_{\psi_1}f(z)dz + \int_{\lambda_2}f(z)dz + \int_{\psi_2}f(z)dz\right)\,.

$$

From the equality with the iterated limits, we call the first integral $I_1$. We will prove

$$

\lim_{r \to 0^+}\lim_{\delta \to 0^+}\int_{\lambda_1}f(z)dz = \int_1^2 f(x)dx\,.

$$

Proof 1. Note that $\operatorname{Arg}(z-1),\operatorname{Arg}(z-2) \in (-\pi,\color{blue}{\pi}]$. We use the parameterization $z = t + i\delta$, for $1+\epsilon \leq t \leq 2-\epsilon$, to get

$$

\begin{align}

I_1 &= \lim_{r \to 0^+}\lim_{\delta \to 0^+}\int_{\lambda_1}f(z)dz \\

&= \lim_{r \to 0^+}\lim_{\delta \to 0^+} \int_{1+\epsilon}^{2-\epsilon} \frac{1}{\sqrt{t+i\delta-1}\sqrt{t+i\delta-2}}dt \\

&= \lim_{r \to 0^+}\lim_{\delta \to 0^+} \int_{1+\epsilon}^{2-\epsilon} \frac{1}{\sqrt{|t+i\delta-1|}\exp\left(\frac{i}{2}\operatorname{Arg}(t+i\delta-1)\right)\sqrt{|t+i\delta-2|}\exp\left(\frac{i}{2}\operatorname{Arg}(t+i\delta-2)\right)}dt\tag{1}\\

&= \lim_{r \to 0^+}\int_{1+\sqrt{r^{2}-0^{2}}}^{2-\sqrt{r^{2}-0^{2}}}\frac{1}{\sqrt{\left|t+i\left(0\right)-1\right|}\exp\left(\frac{i}{2}\cdot\color{green}{0}\right)\sqrt{\left|t+i\left(0\right)-2\right|}\exp\left(\frac{i}{2}\cdot\color{blue}{\pi}\right)}dt \\

&= \int_{1}^{2}\frac{1}{\sqrt{t-1}\sqrt{2-t}i}dt \tag{2}\\

&= \int_{1}^{2}\frac{1}{\sqrt{t-1}\sqrt{t-2}}dt \\

&= \int_1^2 f(x)dx\,. \\

\end{align}

$$

This concludes the first proof. $\square$

From the equality with the iterated limits, we call the second integral $I_2$. We will prove

$$

\lim_{r \to 0^+}\lim_{\delta \to 0^+}\int_{\lambda_2}f(z)dz = \int_1^2 f(x)dx\,.

$$

Proof 2. Note that $\operatorname{Arg}(z-1),\operatorname{Arg}(z-2) \in (\color{red}{-\pi},\pi]$. We use the parameterization $z = -t -i \delta$, for $\epsilon - 2 \leq t \leq -1-\epsilon$, to get

$$

\begin{align}

I_3 &= \lim_{r \to 0^+}\lim_{\delta \to 0^+}\int_{\lambda_2}f(z)dz \\

&= -\lim_{r \to 0^+}\lim_{\delta \to 0^+} \int_{\epsilon-2}^{-1-\epsilon} \frac{1}{\sqrt{-t -i \delta-1}\sqrt{-t -i \delta-2}}dt \\

\overset{-t=x}=& \lim_{r \to 0^+}\lim_{\delta \to 0^+}\int_{2-\epsilon}^{1+\epsilon} \frac{1}{\sqrt{x-i\delta-1}\sqrt{x-i\delta-2}}dx \\

&= \lim_{r \to 0^+}\lim_{\delta \to 0^+}\int_{2-\epsilon}^{1+\epsilon}\frac{1}{\sqrt{|x-i\delta-1|}\exp\left(\frac{i}{2}\operatorname{Arg}(x-i\delta-1)\right)\sqrt{|x-i\delta-2|}\exp\left(\frac{i}{2}\operatorname{Arg}(x-i\delta-2)\right)}\\ \tag{1}

&= \lim_{r \to 0^+}\int_{2-\sqrt{r^{2}-0^{2}}}^{1+\sqrt{r^{2}-0^{2}}}\frac{1}{\sqrt{\left|x-i\left(0\right)-1\right|}\exp\left(\frac{i}{2}\left(\color{green}{0}\right)\right)\sqrt{\left|x-i\left(0\right)-2\right|}\exp\left(\frac{i}{2}\left(\color{red}{-\pi}\right)\right)}dx \\

&= \int_{2}^{1}\frac{1}{\sqrt{x-1}\sqrt{2-x}\left(-i\right)}dx \\

&= \int_{1}^{2}\frac{1}{\sqrt{x-1}\sqrt{x-2}}dx \tag{2}\\

&= \int_{1}^{2}f(x)dx\,. \\

\end{align}

$$

This concludes the second proof. $\square$

The small circular contour integrals are a lot easier to calculate. For the contour on the left, we use the parameterization $z = 1+re^{-it}$, for $\arctan\left(\frac{\delta}{\epsilon}\right) \leq t \leq 2\pi - \arctan\left(\frac{\delta}{\epsilon}\right)$, to get

$$

\lim_{\delta \to 0^+} \int_{\psi_2} f(z)dz = \int_{0}^{2\pi}\frac{-rie^{-it}}{\sqrt{1+re^{-it}-1}\sqrt{1+re^{-it}-2}}dt = -i\sqrt{r}\int_{0}^{2\pi}\frac{e^{-it}}{\sqrt{e^{-it}}\sqrt{re^{-it}-1}}dt \overset{r \to 0^+}\to 0\,.

$$

A similar proof follows for the integral over the right contour:

$$\lim_{\delta \to 0^+} \int_{\psi_1} f(z)dz \overset{r \to 0^+}\to 0\,.$$

Going back to $\mathcal{C}$, we have

$$

\require{cancel} \oint_{\mathcal{C}}f(z)dz = \int_1^2 f(x)dx + \cancelto{0}{\lim_{r \to 0^+}\lim_{\delta \to 0^+} \int_{\psi_1} f(z)dz} + \int_1^2 f(x)dx + \cancelto{0}{\lim_{r \to 0^+}\lim_{\delta \to 0^+}\int_{\psi_2}f(z)dz}\,.

$$

Finally, we conclude

$$

\bbox[15px,border:5px inset #878787]{2\int_1^2 f(x)dx = \oint_{\mathcal{C}}f(z)dz}

$$

and we're finished! $\blacksquare$