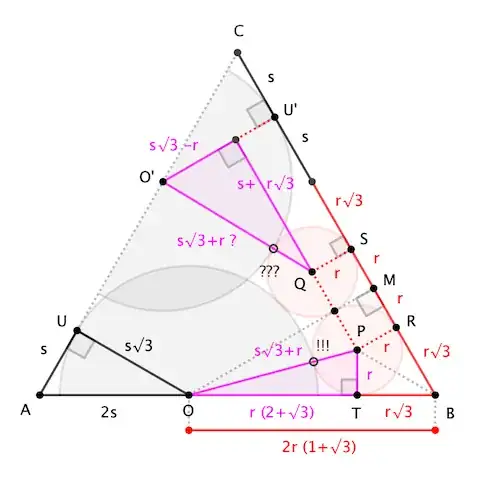

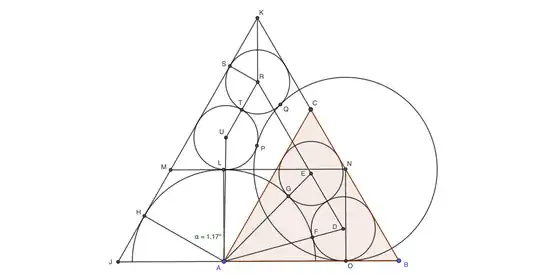

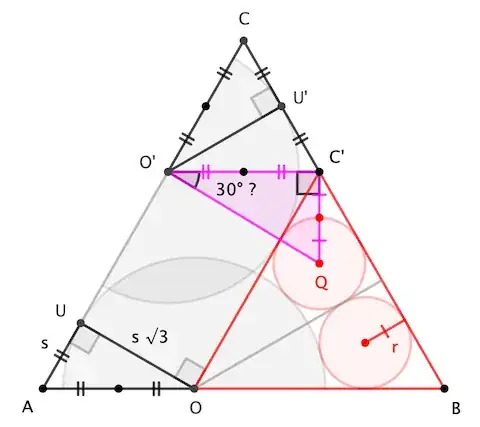

tl;dr: If the green and red circles are the same size, then a rotated copy of the semicircle is tangent to a red circles. The tangencies lead to inconsistent Pythagorean conditions in the (purple) right triangles shown in the figure.

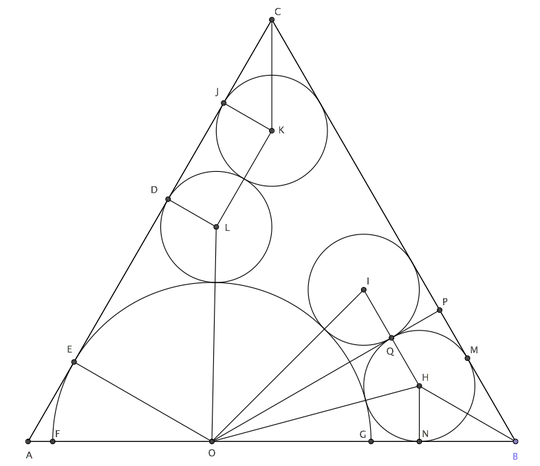

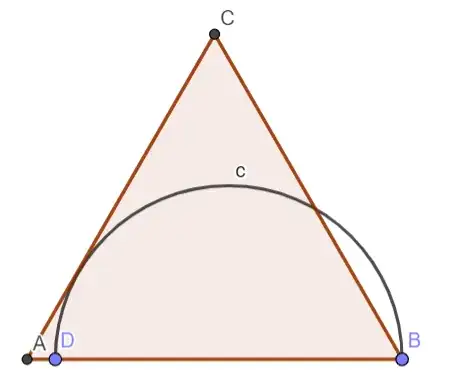

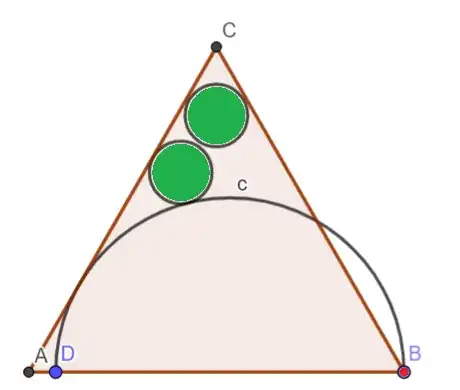

Consider equilateral $\triangle ABC$ with (black) semicircle centered at $O$ on $AB$, and (red) circles centered at $P$ and $Q$. Let the semicircle be tangent to $AC$ at $U$, let $\bigcirc P$ be tangent to $BC$ and $AB$ at $R$ and $T$, and let $\bigcirc Q$ be tangent to $BC$ at $S$.

Also, rotate the semicircle $120^\circ$ about the triangle's center to have center $O'$ on $AC$ and tangent point $U'$ on $BC$. If OP's green circles are congruent to the reds, then this rotated semicircle should be tangent to $\bigcirc Q$. We'll see if that's viable.

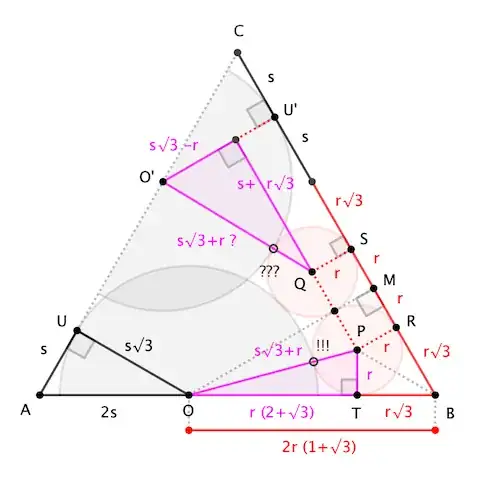

Now, if semicircle $O$ is tangent to the circles, then $O$ lies on the perpendicular bisector of $PQ$; thus, the perpendicular from $O$ meets $BC$ meets midpoint $M$ of $RS$, so that $\bigcirc P$ is the incircle of $\triangle OBM$.

Exploiting $30^\circ$-$60^\circ$-$90^\circ$ triangles ... If the radius of the semicircle is $s\sqrt{3}$, we have $|AU|=|CU'|=s$ and $|AO|=2s$; if the common radius of the circles is $r$, then $|RM|=|SM|=r$, $|BR|=|BT|=r\sqrt{3}$, and $|BO|=2|BM|=2r(1+\sqrt{3})$.

Observe that the semicircle-circle tangency is encoded in right triangle $\triangle OPT$, giving the Pythagorean condition

$$(s\sqrt{3}+r)^2 = r^2 + r^2(2+\sqrt{3})^2 \tag{1}$$

We could explicitly solve this for, say, $s$ in terms of $r$, but we needn't bother. All we need to notice is $s\sqrt{3}$ is definitely not an integer multiple of $r$.

We conclude that the triangle $QO'$ is the hypotenuse of a right triangle with legs $s+r\sqrt{3}$ and $s\sqrt{3}-r$. Hence, if semicircle $O'$ is tangent to $\bigcirc Q$, then $|QO'|=s\sqrt{3}+r$, and

$$\begin{align}

(s\sqrt{3}+r)^2 = (s+r\sqrt{3})^2+(s\sqrt{3}-r)^2 &\quad\to

\quad

(s-r\sqrt{3})^2=0 \\

&\quad\to\quad

|OU| = s\sqrt{3}=3r \tag{2}

\end{align}$$

However, a semicircle-to-circle radius ratio of $3:1$ violates the observation about $(1)$. Consequently, OP's red and green circles are not the same size. $\square$

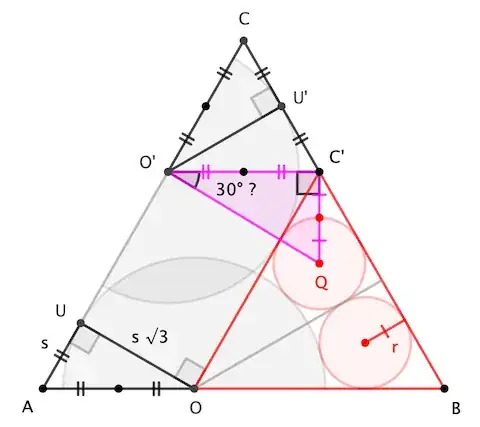

Addendum. Here's a sketch of a slightly more straightforward approach to relation $(2)$.

Let $C'$ complete equilateral $\triangle OBC'$. The tangency of semicircle $O$ with the red circles implies that the distance from $OC'$ to $AC$ is the semicircle's radius; hence, the rotated semicircle $O'$ is automatically tangent to this line.

For semicircle $O'$ to be tangent to red circle $\bigcirc Q$, they'd have to share a point of tangency with $OC'$; thus, $O'Q\perp OC'$, which implies that $\triangle O'QC'$ is $30^\circ$-$60^\circ$-$90^\circ$, giving immediately $s=r\sqrt{3}$ (reconfirming $(2)$).