Let $\mathcal{C}_a$ be the lateral surface of a right circular cone of height $a$ and base radius $1$. Let $\mathcal{C}_a^3$ denote the product $\mathcal{C}_a \times \mathcal{C}_a \times \mathcal{C}_a$, whose points are triples $(A,B,C)$ on that cone. We endow $\mathcal{C}_a$ with its natural surface-area measure. Then $\mathcal{C}_a^3$ inherits the product measure. A random triangle is thus a random point in $\mathcal{C}_a^3$. Define

$$ \mathcal{A}_a = \bigl\{(A,B,C)\in \mathcal{C}_a^3 : \triangle ABC \text{ is acute}\bigr\}. $$

The probability $P_{\text{cone}}(a)$ that a random triangle is acute is

$$ P_{\text{cone}}(a) = \frac{\text{Vol}_{\text{5D}}\bigl(\mathcal{A}_a\bigr)}{\,\text{Vol}_{\text{5D}}\bigl(\mathcal{C}_a^3\bigr)}. $$

Here Vol$_{\text{5D}}$ means 5-dimensional volume in the product space.

Likewise, for the cylinder $\mathcal{Z}_b$ of height $b$ and radius 1, set

$$ \mathcal{A}_b^\prime = \bigl\{(A,B,C)\in \mathcal{Z}_b^3 : \triangle ABC \text{ is acute}\bigr\}, \qquad P_{\text{cyl}}(b) = \frac{\text{Vol}\bigl(\mathcal{A}_b^\prime\bigr)} {\text{Vol}\bigl(\mathcal{Z}_b^3\bigr)}. $$

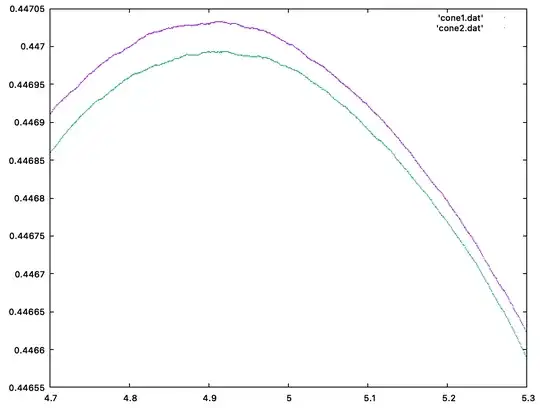

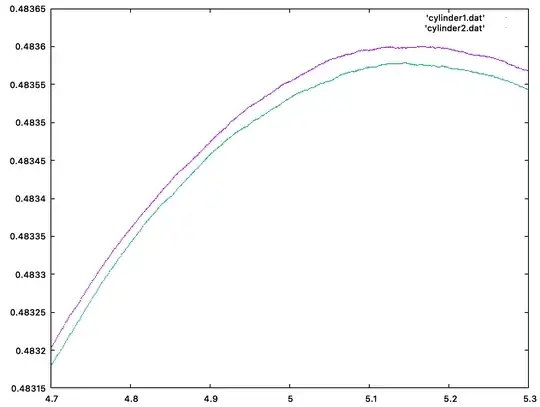

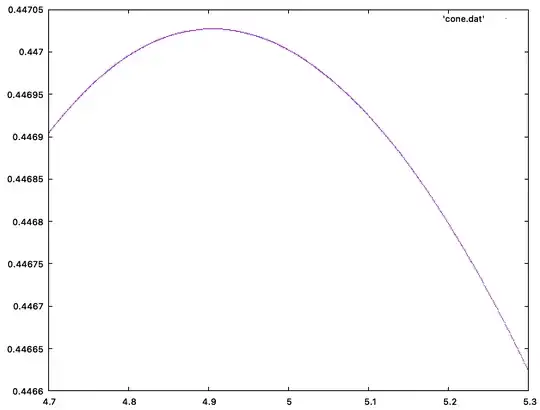

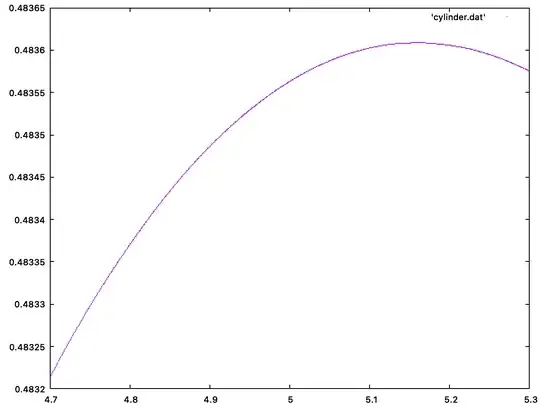

Our goal is to understand where $P_{\text{cone}}(a)$ and $P_{\text{cyl}}(b)$ achieve their maxima and to see whether those maxima coincide (i.e. $a^*=b^*$?) or differ.

Consider a height functional $\Phi\colon \mathcal{C}_a^3 \to \mathbb{R}$ that, loosely speaking, measures the vertical extent of the triple $(A,B,C)$. For instance, define

$$ \Phi(A,B,C) = \bigl[\max\{z(A), z(B), z(C)\}\bigr] - \bigl[\min\{z(A), z(B), z(C)\}\bigr], $$

where $z(P)$ is the $z$-coordinate of point $P$. For each real number $t\in [0,a]$, define

$$ S_a(t) = \{(A,B,C)\in \mathcal{C}_a^3: \Phi(A,B,C) = t\}. $$

Then $\mathcal{C}_a^3$ is naturally stratified by these level sets $S_a(t)$. Consider

$$ S_a^\text{acute}(t) = S_a(t)\,\cap\,\mathcal{A}_a = \{\,(A,B,C) : \Phi(A,B,C)=t, \text{ and } \triangle ABC \text{ is acute}\}. $$

The measure of $S_a^\text{acute}(t)$ as $t$ varies gives us a handle on how the acuteness probability changes with the cone's height $a$.

We do a similar construction for the cylinder $\mathcal{Z}_b$. In that case, height is even more literal, since the shape is just $\theta\in[0,2\pi)\times z\in[0,b]$. We define

$$ \Phi^\prime(A,B,C) = \max\{z(A),z(B),z(C)\} - \min\{z(A),z(B),z(C)\}, $$

and slice $\mathcal{Z}_b^3$ accordingly.

If a triangle $\triangle ABC$ has a large vertical extent (e.g., one vertex is near the top of the shape and others are near the bottom), then it is more likely that one angle is obtuse. Conversely, if the points are all at similar heights, there is less chance of an obtuse angle, because the triple is more horizontal, resembling a small flat subtriangle near a single horizontal cross-section.

These heuristics suggest that as the shape's height parameter $a$ or $b$ grows large, we eventually get a lower acute-triangle probability. As the shape's height becomes very small, the shape degenerates to a thin band or nearly a disk, also decreasing the acute probability. Hence there is a sweet spot in between—i.e., we anticipate a single interior maximum in $a$ or $b$.

As $a\to 0$, the shape collapses into a narrow frustum near the tip. In that limit, the geometry forces many triangles to have the apex angle close to $180^\circ$, thus decreasing the acute probability. We can prove $\lim_{a\to 0} P_{\text{cone}}(a) = 0$. As $a\to \infty$, the shape is tall and random points are often at significantly different heights, boosting the chance that a top–bottom edge becomes the largest side, frequently causing an obtuse angle. We can show $\lim_{a\to \infty} P_{\text{cone}}(a) = 0$ as well.

In between, if you track $P_{\text{cone}}(a)$ as a function of $a$, continuity arguments guarantee a maximum for some finite $a^*$. A deeper argument shows that maximum is unique. Exactly the same reasoning applies to the cylinder with parameter $b$. So there exist unique $a^*$ and $b^*$ that maximize the acute probabilities for cone and cylinder, respectively.

To compare $a^*$ and $\sqrt{5}$ (or $b^*$ and $\sqrt{5}$), we can exploit a two-slice argument. Pick two values $a_1 < \sqrt{5}$ and $a_2 > \sqrt{5}$. Estimate the measure of $\mathcal{A}_{a_1}$ and $\mathcal{A}_{a_2}$ carefully by partitioning $\mathcal{C}_{a_2}^3$ into subregions: those for which the triple $(A,B,C)$ would remain acute if we shrunk $a_2$ to $a_1$, and those for which it would turn obtuse upon decreasing the height. This is a matter of analyzing how each triple's vertical/spatial configuration changes: if all points remain within a vertical band that fits inside height $a_1$, then if it was acute for $a_2$, it should remain acute for $a_1$. In other configurations, it might lose acuteness upon height contraction.

Compare the volumes of these subregions. Bounding their relative measures, we can show that if $\sqrt{5}$ were indeed the maximizer, it would force certain volume inequalities that are violated by direct geometric estimates. We can show something like the measure of triples that are acute at $a_2$ but not at $a_1$ is large enough to shift the peak away from $\sqrt{5}$.

An analogous argument works for the cylinder. We can prove that for the cone, $a^*$ must lie below $\sqrt{5}$, while for the cylinder, $b^*$ must lie above $\sqrt{5}$. Thus $a^*\neq b^*$ and they straddle $\sqrt{5}$.