In a nutshell: is the following the $(\forall)$-introduction rule in Natural Deduction?

$$\frac{\phi[t/x]}{\forall x\phi}\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \begin{matrix}\text{provided the term $t$ does not occur in $\phi$}\\ \text{nor in any undischarged assumption in the proof of $\phi[t/x]$}\end{matrix} $$

I began learning about natural deduction from these notes where the $(\forall)$-introduction rule is written as above except $t$ is a constant, not an arbitrary term. The same happens with $(\exists)$-elimination. Such was one of the reasons I was confused when learning that we are allowed to subsitute general terms when using the rule. From that point on, I have been assuming that the correct $(\forall)$-introduction rule is as written in the notes, but with $t$ standing for an arbitrary term. Realizing I've been assuming this without ever having read the correct rule anywhere explicitly, I thought I should check that my understanding is right.

Edit: I asked the following in a separate post which was closed as a duplicate, so I guess I must ask it here:

The $\forall I$ rule in Val Dalen's Logic and Structure is $\def\f{\varphi}$

$$\frac{\f(x)}{\forall x \f(x)}$$

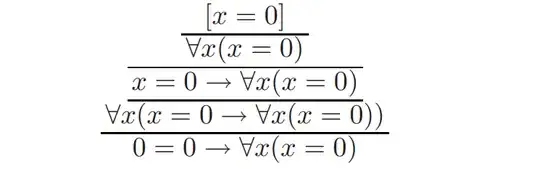

where $x$ does not appear free on any hypothesis on which $\f(x)$ depends. As an explanation for this restruction, the author shows that if the restriction was removed we could argue as follows:

which is obviously incorrect. As he explains, the $\forall$ introduction at the first step was illegal. What confuses me here is that I thought

$$T\vdash \f(x) \ \ \ \ \text{ if and only if } T\vdash \forall x \f(x)$$

for any $\f$ with free $x$. I even thought to have proven it. Therefore, the first step in Van Dalen's erroneous proof would be valid, and so would the erroneous argument as a whole.

What am I missing?