On a circle, choose three uniformly random independent points $A,B,C$.

Inside the circle, choose a uniformly random independent point $D$.

Triangle $ABC$ is called "happy" if it contains $D$.

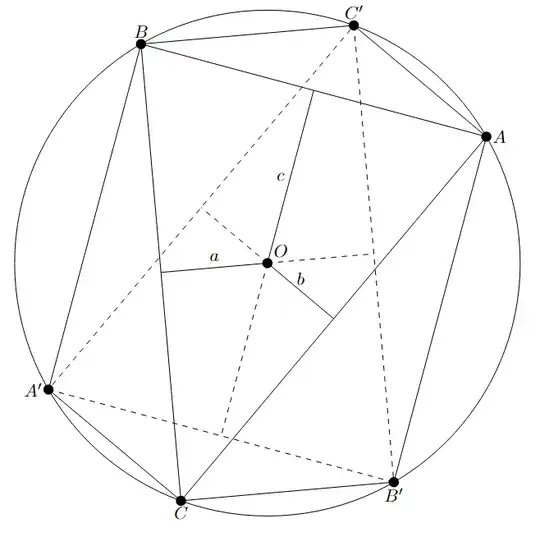

What is the probability that a happy triangle contains the centre of its circumcircle?

Simulations suggest that the probability is $1/2$.

Given the simplicity of this probability, I wonder if there is an intuitive explanation.

Context

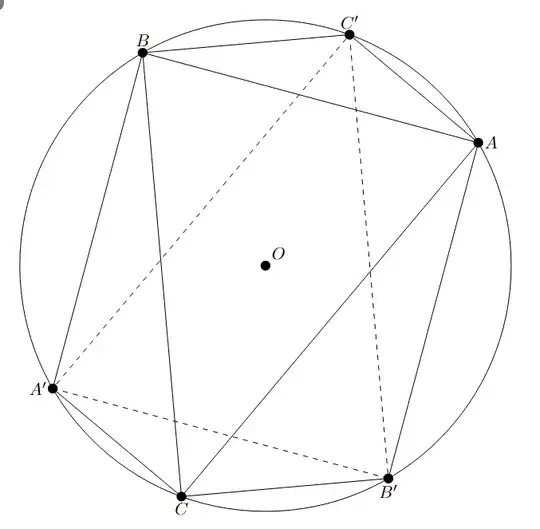

This is a variation of the classic question, "What is the probability that a triangle, whose vertices are three random points on a circle, contains the centre of the circle?" The answer to that question is $1/4$, and there is an intuitive explanation.

My attempt

Assume the circle is a unit circle.

From circle triangle picking, the expected area of $\Delta ABC$ is $\dfrac{3}{2\pi}$.

$$\therefore P(\Delta ABC\text{ contains }D)=\dfrac{\frac{3}{2\pi}}{\text{Area of circle}}=\dfrac{3}{2\pi^2}$$

Call the centre of the circle $O$.

$$P\left(\text{$\Delta ABC$ contains $O$ | $\Delta ABC$ contains $D$}\right)$$

$$=\frac{P(\text{$\Delta ABC$ contains $O$ and $D$})}{P(\text{$\Delta ABC$ contains $D$})}$$

$$=\dfrac{2\pi^2}{3}P\left(\text{$\Delta ABC$ contains $O$ and $D$}\right)$$

I do not know how to calculate $P\left(\text{$\Delta ABC$ contains $O$ and $D$}\right)$.

I used this formula to make my simulations.

Possibly related question: "Probability that a random triangle with vertices on a circle contains an arbitrary point inside said circle"

Add this one to the list?

I might add this question to my list of probability questions that have answer $1/2$ but resist intuitive explanation.

Other elegant properties of happy triangles?

Simulations suggest that, for a happy triangle inscribed in a unit circle:

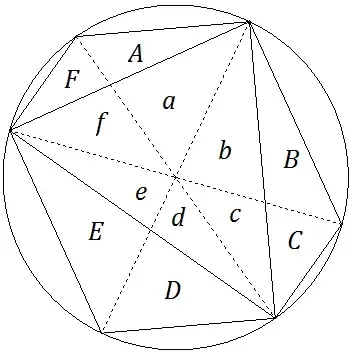

- The expected area is $\pi/4$. (Thus, a happy triangle divides the circle into four regions of equal expected area.)

- The expected shortest side length is $1$.

- The expected product of the three side lengths is $\pi$.

- The probability that it contains (another) random point in the circle is $1/4$.

- If the sides are, in random order, $a,b,c$, then $P(ab<c)=1/3$. (For not-necessarily-happy $\Delta ABC$, this probability is $1/2$).