Suppose random variables $X$ and $Y$ are i.i.d. Normal$(0,1)$. Consider the following events, where $\varepsilon>0, c>0$:

$$\begin{align*} Q&=\{(x,y)\in\Bbb R^2: x>c, y>c\}\\ C&=\{(x,y)\in Q:y<x-\varepsilon\}\\ D&=\{(x,y)\in Q:x-\varepsilon<y<x\}\\ D'&=\{(x,y)\in Q:x<y<x+\varepsilon\}\\ C'&=\{(x,y)\in Q:y>x+\varepsilon\}\\ \end{align*}$$

Note that $Q$ is the "shifted 1st-quadrant" with origin shifted to the point $(c,c)$ on the diagonal line $y=x$.

Now consider the probability that the random point $(X,Y)$ falls in the narrow diagonal strip $D\cup D^\prime$ (with $\varepsilon>0$ arbitrarily small), given that it falls in the remote "shifted 1st-quadrant" $Q$ (with $c>0$ increasingly large). Denoting this probability $p(\varepsilon,c)$, I will (later) derive the following formula:

$$p(\varepsilon,c)=1-2\,{\int_{c+\varepsilon}^\infty\phi(x)\Phi(x-\varepsilon)\,dx-\bar\Phi(c+\varepsilon)\Phi(c) \over \bar\Phi(c)^2}\tag{1}$$

where $\phi$ and $\Phi$ are the standard normal p.d.f. and c.d.f., respectively, and $\bar\Phi=1-\Phi$.

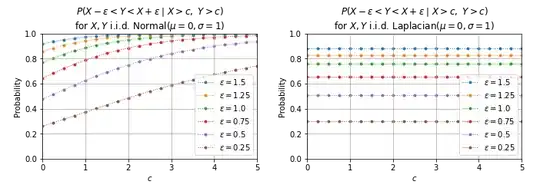

Since I could find no way to simplify the integral in this equation, I evaluated it numerically to obtain the following results -- with corresponding results for i.i.d. Laplacian random variables shown for comparison/contrast:

Question: How can it be proved that (as suggested by the above results) $\lim\limits_{c\to\infty}p(\varepsilon,c)=1$ for all $\varepsilon>0$ (or even for some particular $\varepsilon>0$)?

Actually, my immediate question is whether it's even plausible that no matter how thin the strip $D\cup D^\prime$, the point $(X,Y)$ is practically certain to fall there, given that it falls in a "shifted 1st-quadrant" $Q$ sufficiently far out on the diagonal!?

If this is the correct asymptotic behavior, it seems sufficiently "paradoxical" that surely it (or something similar) would be mentioned in the literature. (?)

NB: I've double-checked the precision of the numerical integration, and I also ran Monte Carlo simulations that confirm (though with fewer cases) the behavior shown in the above plots.

Derivation of Eq.(1)

(This is "spin-off" from my answer to a related question.)

$$\begin{align*} p(\varepsilon,c)& := P(D\cup D^\prime\mid Q)\\ &\overset{1}{=}2\,P(D\mid Q)\\ &\overset{2}{=}2\,\left({1\over2}- P(C\mid Q)\right)\\ &=1-2\,{P(C)\over P(Q)}\\[2ex] &=1-2\,{\int_{c+\varepsilon}^\infty\phi(x) \int_c^{x-\varepsilon}\phi(y)\,dy\, dx \over \bar\Phi(c)^2}\\[2ex] &=1-2\,{\int_{c+\varepsilon}^\infty\phi(x)\left(\Phi(x-\varepsilon)-\Phi(c)\right)\, dx \over \bar\Phi(c)^2}\\[2ex] p(\varepsilon,c)&=1-2\,{\int_{c+\varepsilon}^\infty\phi(x)\Phi(x-\varepsilon)\,dx-\bar\Phi(c+\varepsilon)\Phi(c) \over \bar\Phi(c)^2} \end{align*}$$

where the equalities (1) and (2) are justified because ...

- The joint p.d.f. is symmetric and centered on the origin $O$.

- $P(C\cup D\mid Q)=P(C^\prime\cup D^\prime\mid Q)={1\over2}P(Q\mid Q)={1\over2}$, again because of the symmetry of the joint p.d.f.