People sometimes talk about "projecting onto a sphere" analogously to projection onto a plane, but how is this defined (a formula would be nice)? It's not obvious to me how we should handle points in the interior in the general case, where the centre of projection is allowed to move away from the centre of the sphere. I explain below why this is harder than it sounds. The following, appealingly intuitive, approach is wrong: "imagine a light source at the centre of projection; find the equation of a ray of light to the point $P$ and solve a quadratic equation to find where it intersects the sphere. If there are two intersection points, the image $P'$ is the one on which $P$ casts a shadow."

To recap central projection from a point $C$ (the centre of projection) onto a plane $\Pi$, first note $C$ must not lie in $\Pi$ and has no image. For any other point $P$, the image $P'$ is the point of intersection (if it exists) between the line $CP$ and $\Pi$. If $CP$ is parallel to $\Pi$ then $P$ has no image: the only points without an image lie in a plane through $C$ parallel to $\Pi$. If $P$ has image $P'$ then $P'$ is also the image of every point on $CP$ except $C$ itself. This applies whether $P$ lies between $C$ and $\Pi$, or $C$ lies between $P$ and $\Pi$: in this sense projection is not just "where does $P$ casts a shadow on the plane when illuminated by a point light source at $C$", since if $C$ is in the middle then no shadow can be cast! Nor do mathematicians even seem to care whether $P$ lies on the far side of $\Pi$ from $C$. (Ordering matters in applications like computer graphics; it turns out to matter for projection onto a sphere too.) Take a unit vector $\mathbf{\hat{u}}$ parallel to $CP$, then solve for $t$ such that the point $\mathbf{p} + t \mathbf{\hat{u}}$ satisfies the equation of $\Pi$. The equations will either be inconsistent (so $CP$ is parallel to the plane and $P$ has no image) or have a unique solution $t=t_0$ (so the image has coordinates $\mathbf{p'} = \mathbf{p} + t_0 \mathbf{\hat{u}}$).

Many questions on this site concern "radial" projections onto a sphere, where the centre of projection $C$ is taken to be the centre of the sphere (often a unit sphere, but let's say it has radius $r$): examples here, here, here, and here. If the points we are projecting lie on a plane that does not pass through $C$, then this problem is the inverse of gnomonic projection from the sphere to the plane. The formula for projecting radially onto the sphere is straightforward, particularly in spherical coordinates where we just renormalise the radial distance.

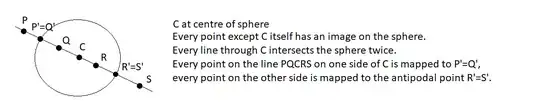

In some respects what we are doing resembles projection onto a plane, e.g. $C$ still does not lie on the surface we are projecting onto. But now $C$ is the only point without an image. With $\mathbf{p'} = \mathbf{p} + t \mathbf{\hat{u}}$, substituting into the equation of the sphere gives $\| \mathbf{p'} - \mathbf{c} \|^2 = r^2$ so this time we obtain a quadratic for $t$. In radial projection, every line $CP$ intersects the sphere at two (antipodal) points so the quadratic always has two roots. I believe the root corresponding $P'$ can be chosen by any of these equivalent rules:

- Pick the root corresponding to the intersection point on the same side of $C$ as $P$.

- Pick the root which is smaller in magnitude (i.e. the intersection point closer to $P$).

- Pick the root which is larger in value, assuming $\hat{u}$ was chosen in the direction $\vec{CP}$, as would be natural from a "shadow-casting" point of view. Move between the two intersection points in the direction $\vec{CP}$, and the point corresponding to the larger root is the one you finish up on. To see this is equivalent to (1), write the coordinates of $C$ as $\mathbf{c} = \mathbf{p} + t_c \mathbf{\hat{u}}$. Clearly $t_c$ is sandwiched between the roots of the quadratic, $t_- < t_c < t_+$. Since $t_c < t_p$ if $\hat{u}$ is in the direction $\vec{CP}$, the root on the same side of $C$ as $P$ is $t_+$.

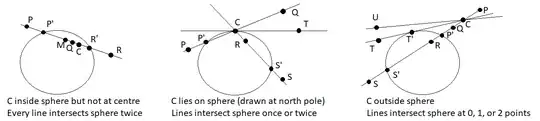

But if I move $C$ to some other point in the interior of the sphere, the first and second rules are no longer equivalent. See the left diagram below. It's still true every line intersects the sphere exactly twice, and there is no problem projecting points outside the sphere onto the sphere (here I believe the 3 formulations remain equivalent). But consider the chord $P'MQCR'$, where $M$ is the midpoint of the chord. Should $Q$ be projected to $P'$ because it lies that side of $C$, or should it be projected to $R'$ because that's closer? If anybody thinks the latter, where do they suggest $M$ should be projected, given it is equidistant from $P'$ and $R'$?

If $C$ lies on the sphere (let's say at the North Pole), then projecting points on the South Pole's tangent plane onto the sphere is the inverse of stereographic projection: this inverse problem attracts many question here. Unlike projecting onto a plane, our centre of projection now lies on the surface onto which we are projecting! If we believe in the idempotence of projections, does this mean $C$ now has an image, namely $C'=C$? Similarly, are we satisfied that every point either in or above the tangent plane to the North Pole is mapped to $C$? Note if $T$ lies in this tangent plane, the line $CT$ meets the sphere only once. But even for lines intersecting the sphere twice, our first formulation of which root to pick no longer make sense: "the intersection point on the same side of $C$ as $P$" is meaningless when $C$ is one of the intersection points, and is no longer equivalent to the third formulation since we no longer have $t_- < t_c < t_+$. Nevertheless, it's clear how we'd want to project points outside the sphere that lie below the tangent plane to the North Pole. Presumably we want every point $R$ in the interior of the sphere to map to the other point where $CR$ intersects the sphere ($S'$ on the diagram), rather than to $C$, even if they lie very close to $C$: this can be achieved by using the third formulation, picking the larger root.

Things get more complicated if the centre of projection is outside the sphere. Now lines may intersect the sphere never, once, or twice. Points like $U$ in the rightmost diagram, which lie outside a certain (double) cone with apex at $C$, have no image. Points like $T$ lying on that cone get projected onto points like $T'$ on the circle in which the sphere and cone touch; our quadratic for $t$ has repeated roots in this case. For points inside the cone, the line intersects the sphere twice so we need to pick which root to select. For points inside the cone but outside the sphere, their image should surely be the nearer of the two intersection points. So picking the root of $t$ with the smaller magnitude still works; both roots are now the same side of $C$ so the first formulation doesn't make sense, and the "larger value of $t$" formulation would project points like $Q$, which lie between the centre of projection and the sphere, over to $S'$ on the wrong (far) side of the sphere! But what about points like $R$ that lie inside the sphere? We saw already the "smaller magnitude" approach is unsatisfactory here — consider the centre of the sphere, for instance, which is equidistant from the two intersection points. Is it conventional to adopt the "largest value" approach, and send points in the interior of the sphere to points like $S'$ on the far side of the sphere, i.e. below the circle where the sphere meets the cone?

Note that in the limit as $C$ moves away to infinity, the cone of points which have an image on the sphere becomes a cylinder, and we are now performing a parallel projection. Even in this case, it's not clear where we should map points in the interior of the sphere: for consistency with the above suggestion, the interior should map to the hemisphere on the far side from an imagined light source at infinity, as if it were casting a shadow on the inner surface of the sphere. This would be unusual, since generally when we perform a parallel projection we don't care about the sign of the direction vector we are projecting parallel to. For us, a reversal of this sign would indicate $C$ had gone to infinity in the opposite direction, so it seems the interior of the sphere should cast its shadow on the opposing hemisphere.

In summary, I'd like to know if there's a neat formula that covers all the above cases, with radial projection as a special case and perhaps recovering parallel projection in the limiting case? Failing that, is projection onto a sphere even well-defined — particularly for points in the interior which cause most of the trouble above? If there is such a definition, does it give us a natural and consistent convention to decide which of the two roots to pick when we use the quadratic equation method to find the intersection points? The best I can come up with is: "if $P$ lies on the sphere then $P' = P$; if $P$ lies outside the sphere, solve the quadratic for $t$ and take the root with lower magnitude; if $P$ lies inside the sphere, take the root with greater value" which seems to behave reasonably like I'd expect, but I don't have any justification for it or any idea if it matches established conventions.