1. SOME CLAIMS

Fix a positive real number $\alpha$ and consider

$$

a_k:=\begin{cases}

1,& \{\alpha k\}<1/2, \\

0,& \{\alpha k\}\geq 1/2.

\end{cases}

$$

(Using $\lbrace x\rbrace= x-\lfloor x\rfloor\in [0,1)$, the fractional part of a real number $x$.)

Then, form the sequence

$$

b_n=\sum_{k=1}^n \,(-1)^k \,\binom {n-1}{k-1}\, a_k,

$$

and also

$$

c_n=2^{1-n}|b_n|.

$$

I will now make several claims. Hopefully they are true, and hopefully the gaps in the proofs can be filled in.

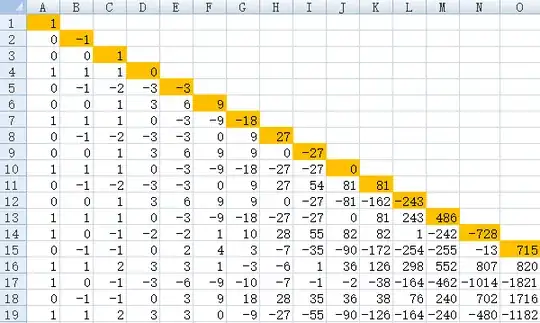

CLAIM 1. When $\alpha=1/\pi$, this gives rise to the sequence in the post, with the first values of $a_k$ being

$$

1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1,

$$

and the first values of $b_n$ being

$$

-1, -1, -1, 0, 3, 9, 18, 27, 27, 0, -81, -243, -486, -728, -715, 105,

2746, 8924, 21537, 45847.

$$

This is easy. We have $\lceil\sin(2k)\rceil=$1 or $0$ precisely if $\{k/\pi\}<1/2$ or $>1/2$, respectively, hence $a_k=\lceil\sin(2k)\rceil$ for $\alpha=1/\pi$. Then use induction (or the formula for powers of the difference operator) to prove the formula for $b_n$.

Define, for $q>r\geq 0$ integers,

$$

f_{n,r,q}=2^{1-n}\sum_{\substack{k=1,\ldots,n\\ k\equiv r\mod q}}^n(-1)^k \binom{n-1}{k-1}.

$$

CLAIM 2. Let $\omega=\exp(2\pi i/q)$. Then

$$

f_{n,r,q}=-\frac 1q\sum_{\ell=0}^{q-1}\frac{(1-\omega^\ell)^{n-1}}{2^{n-1}}\omega^{-\ell (r-1)}.

$$

As a consequence, as $n\to+\infty$,

$$

f_{n,r,q}\to\begin{cases}\frac {(-1)^r}{q},&\mbox{if }q\mbox{ is even},\\ 0,&\mbox{otherwise}.\end{cases}

$$

(See these nice notes, Section 6.)

CLAIM 3. We have $\lim_{n\to+\infty}c_n=0$ unless $\alpha=p/q$ is rational with $p,q$ coprime integers and $q$ equal to twice an odd number, in which case $\lim_{n\to+\infty}c_n=1/q$.

Ideas for a proof:

If $\alpha=p/q$ is rational ($p,q$ coprime integers) then

$$

2^{1-n}b_n=\sum_{\substack{r=0,\dots,q-1 \\ \lbrace rp/q\rbrace<1/2}}f_{n,r,q}

$$

and so, by the previous point, we get

$$

\lim_{n\to+\infty}c_n=\biggl|\lim_{n\to+\infty}2^{1-n}b_n\biggr| = \frac 1q\biggl|\sum_{\substack{r=0,\dots,q-1 \\ \lbrace rp/q\rbrace<1/2}}(-1)^r\biggr|.

$$

It should not be too hard to prove that

$$

\sum_{\substack{r=0,\dots,q-1 \\ \lbrace rp/q\rbrace<1/2}}(-1)^r

=\begin{cases}

\pm1,& \mbox{if }q=2\times\mbox{ odd integer},\\

0,&\mbox{otherwise}.

\end{cases}

$$

If instead $\alpha\not\in\mathbb Q$, we can pick (Dirichlet approximation) a fraction $p/q$ ($p,q$ coprime) such that $|\alpha-p/q|<1/q^2$ with $q$ arbitrarily large. Then $a_k(\alpha)=a_k(p/q)$ for all $k\leq q$ (or, at least, for most of the values, in a way to be made precise!), such that $c_n(\alpha)$ is essentially $c_n(p/q)$

for all $n\leq q$ and one should bound $c_n(p/q)$ in a smart way, using the explicit expression for $f_{n,r,q}$.

I may try to sort out the details in the future.

2. NUMEROLOGY IN THE PLOT AND THE CONTINUED FRACTION EXPANSION OF $\pi$.

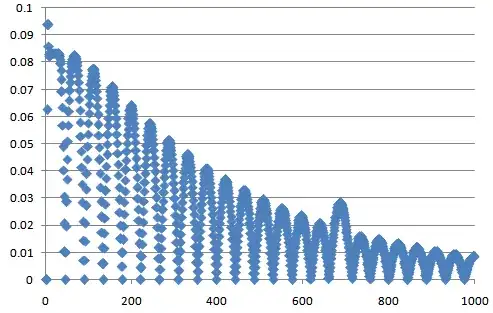

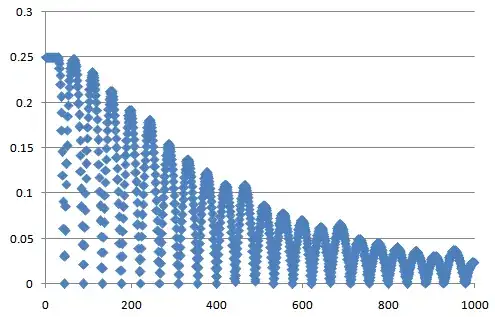

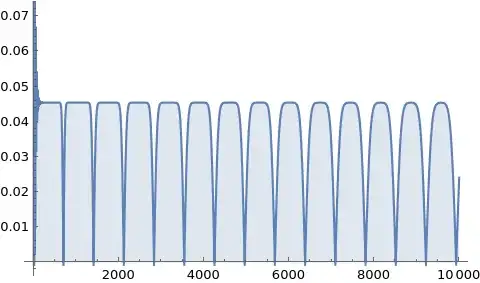

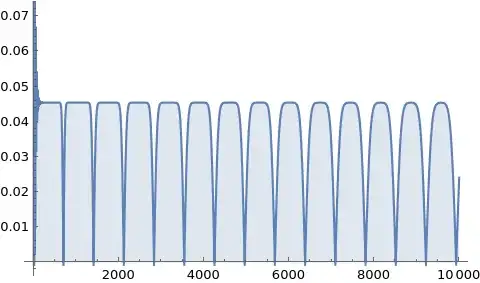

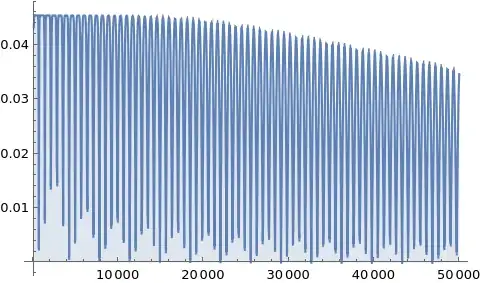

The above facts being established (rather, claimed), let us look at the following plots of $c_n$ for $\alpha=1/\pi$ (i.e., the original quantity of interest in the question, up to a factor of $2$): first for $n=1,\ldots,10000$

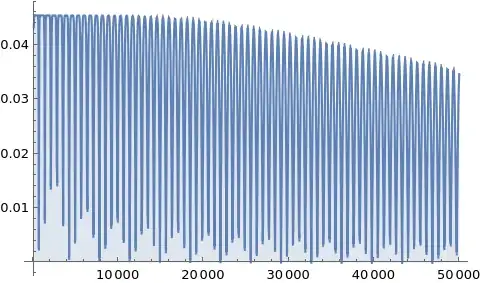

and then for $n=100,\ldots,50000$ (plotting for values multiple of $50$ only)

(The last plot confirms that eventually, in the long run, $c_n\to 0$ for $\alpha=1/\pi$).

It is natural to guess that the following two facts observed in the question might have an interesting explanation in terms of the first few convergents of $\pi$

$$

3,\frac{\color{red}{22}}{7},\frac{333}{106},\frac{\color{red}{355}}{113},\frac{103993}{33102},\ldots

$$

($355/113$ being amazingly good).

The values of $c_n$ at the plateaux are very close to $1/\color{red}{22}$ for the first several plateaux.

The separation between plateaux occurs at values which are very close to even multiples of $\color{red}{355}$.

In fact, an explanation for 1. is that the values of $a_k$ for $\alpha=1/\pi$ and $\alpha=7/22$ coincide for all $k<355$. Since $22$ is twice an odd integer, the graph for $\alpha=7/22$ stabilizes to $1/22$. Since the graph for $\alpha=1/\pi$ must coincide with that for some time, this essentially explains the plateaux and its value $1/22$.

Similarly, the $a_k$'s for $\alpha=1/\pi$ and $113/355$ coincide for all $k<52174$. So, even the larger plot reported above coincides with the one for $113/355$, whence it should not be surprising the all the properties of the plot so far are determined by these first convergents.

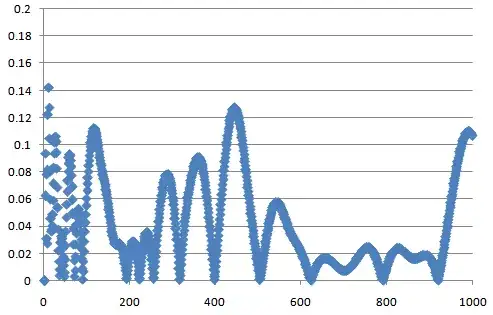

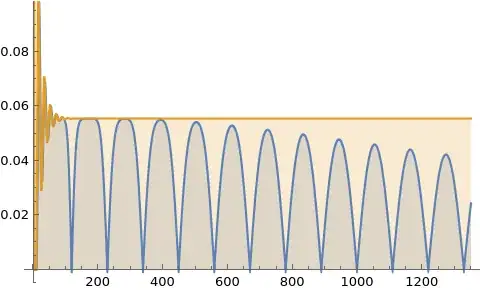

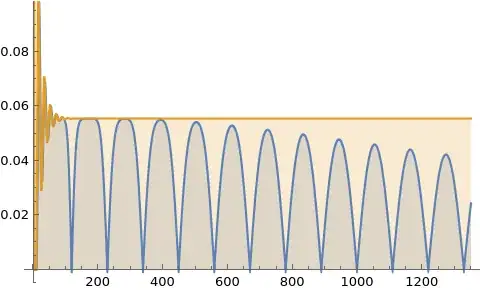

As a similar example we may consider the convergents of $3/55$, which are $\frac 1{18}, \frac 3{55}$. Here are the plots of $c_n$ for these two values: they coincide for a while, then one stabilizes to $\frac 1{18}$ and the other one eventually goes to zero exhibiting a periodicity $2\times 55$. Again, the initial plateaux of the plot for $3/55$ are explained by the first convergent $1/18$.

3. FINAL COMMENTS

In conclusion, comments about the 4 questions in the original post.

Dividing by $2^n$ (rather, by $2^{n-1}$, as it seemed more natural to me) "stabilizes" the sequence $b_n$ probably because $b_n$ is a sum of terms $-a_1,\dots,(-1)^na_n$ (more or less half of which are $\pm 1$s and half $0$s) against binomial coefficients $\binom{n-1}{k-1}$. Therefore,

$$

\sum_{k=1}^n\binom{n-1}{k-1}=2^{n-1}

$$

is the appropriate normalization for such a quantity (which can now be interpreted as an average of terms equal to $\pm 1$ and $0$).

In view of this, plateaux and dips in the plot probably correspond to a different balances of $+1$ and $-1$ in these sums weighted by binomials (constructive or destructive interference of terms of different signs).

The plot eventually goes to zero.