Let $(\Omega, \mathcal{F}, P)$ be a probability triple. The following definitions are from the third chapter of William's Probability with Martingales.

(Definition of a distribution function and law given a random variable)

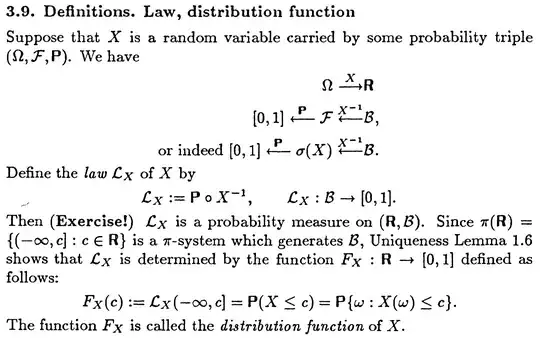

Definition: given a random variable $X$, we define its distribution $F_X:\mathbb{R}\to[0,1]$ and law $\mathcal{L}_X:\mathcal{B}\to[0,1]$ (which is a probability measure) by

\begin{equation}

\label{rel rv d l}

F_X(c) := \mathcal{L}_X(-\infty,c] := P(X\le c) = P\{\omega :X(\omega)\le c\}.

\end{equation}

(Definition of a distribution function in general)

Definition: a distribution function $F$ is a function $\mathbb{R}\to[0,1]$ such that

(a) $F$ is monotonically increasing.

(b) $\lim_{x\to -\infty} F(x) = 0$ and $\lim_{x\to \infty} F(x) = 1$.

(c) $F$ is right-continuous.

The two definitions above gives us the following: a function $F$ is a distribution function if and only if there is some random variable $X$ so that $F=F_X:=c\mapsto P(X\le c)$.

With all this in mind, I wonder how may we define a Law $\mathcal{L}$ in general so as to make the following statement true:

A function $\mathcal{L}$ is a law if and only if there is some random variable $X$ so that $\mathcal{L}=\mathcal{L}_X:=(-\infty,c]\mapsto P(X\le c)$.

Perhaps I should mention that there is a 'trivial' way of answering the question: a law $\mathcal{L}$ is defined as a function $\mathcal{B}\to[0,1]$ such that there exists a distribution $F$ with $F(c) = \mathcal{L}(-\infty,c]$ for any $c\in\mathbb{R}$. However, I'm looking for a definition of a law that does not mention a distribution either.