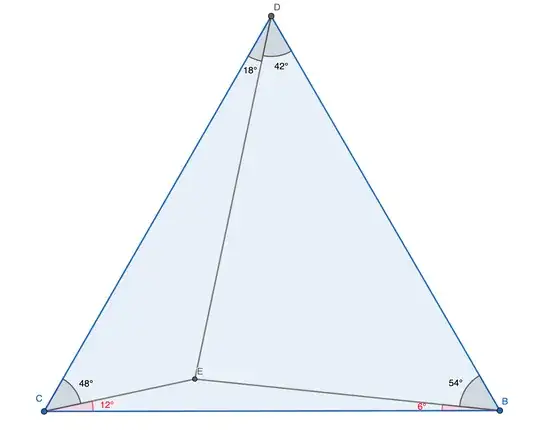

In the equilateral triangle below, $CD, AD$, and $BD$ concur at point $D$. The measures of the angles ($a, b, c, d, e,$ and $f$) are also defined as given in the figure below. Conjecture: There aren't any $a, b, c, d, e,$ and $f$ such that all are different integers without using the combinations of the numbers: $6, 54, 42, 18, 48$, and $12$. (to clarify, all six of these numbers can not be used together, but they can be used together in groups) How can I prove this conjecture mathematically, and what is so special about these six numbers?

My thoughts and work on the problem

I am intentionally omitting the degree signs for convenience.

Using, the Trigonometric Ceva's Theorem, I obtained the following expression:

$$\frac{\sin(a)}{\sin(b)}\cdot\frac{\sin(c)}{\sin(d)}\cdot\frac{\sin(e)}{\sin(f)}= 1$$

which is equivalent to: $$\begin{aligned} \sin(a) \sin(c) \sin(e) = \sin(b) \sin(d) \sin(f) \end{aligned} \label{a}\tag{1}$$

We also know that,

$$a+b=c+d=e+f=60$$

To convert the triple sine product to summations, I used the following "trick". Since, $$\sin(a+c+e)=\sin(b+d+f)$$

and also due to $Eq. (1)$, it is true that: $$\sin(-a+c+e)+\sin(a-c+e)+\sin(a+c-e)$$

$$=\sin(-b+d+f)+\sin(b-d+f)+\sin(b+d-f)$$

Let's substitute $b=60-a, d=60-c$, and $f=60-e$ and let $x=(c+e-a), y=(a+e-c),$ and $z=(a+c-e)$ to simplify things a bit:

$$\sin(x) +\sin(y) +\sin(z)=\sin(60-x)+\sin(60-y) +\sin(60-z)$$

I expanded the $(60-x)$'s using compound angle formulae:

$$\sqrt{3}/2 (\cos(x) + \cos(y) + \cos(z)) - 3/2 (\sin(x) + \sin(y) + \sin(z)) = 0$$

which simplifies to:

$$\sin(30-x) +\sin(30-y) +\sin(30-z)=0$$

but I feel lost in the algebra and don't know what to do next. I want to get to a point where I can easily plug numbers and show that no other numbers satisfy this equation, other than the combinations of the six numbers given at the beginning.

The trigonometric proof of one of the cases may aid to formulate a proof, so I decided to include it as well: For $a=6, b=54, c=42, d=18, e=48, f=12$, $Eq. (1)$ is satisfied, so let's prove it.

Proof. $$ \sin(12°) \sin(18°) \sin(54°)\stackrel{?}{=} \sin(6°)\sin(42°)\sin(48°)$$ Now we use the "trick": $$ \sin(60°)+ \sin(48°)- \sin(24°)\stackrel{?}{=} \sin(84°)+\sin(12°)+\sin(0°)$$ $$\sin(60°)=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \stackrel{?}{=} \sin(12°)+ \sin(24°) - (\sin(48°) -\sin(84°))$$ $$ = 2 \sin(18°) \cos(6°) + 2 \cos(66°) \sin(18°)$$ $$ = 2 \sin(18°) (\cos(6°) + \cos(66°)$$ $$ = 2 \sin(18°) (2\cos(36°)\cos(30°) )$$ $$1 \stackrel{?}{=} 4 \sin(18°) \cos(36°)$$ $$\frac{1}{2} = \cos(36°) \cos(72°)$$ which is true as it is a well-known identity.

Here is the figure of this triangle (rotated):

Given only 6 and 12 degrees (the red angles) the rest of the angles can be found. For the sake of brevity, I will omit the synthetic proofs. For the interested reader, see this link, as it also shows the beauty of synthetic solutions in these types of problems from the perspective of a geometrician. The combinations of $6, 54, 42, 18, 48$, and $12$ often come up in synthetic geometry problems: I even managed to find one in SE.

@KorayUlusan helped me develop a code to test the conjecture by brute force in Python. Turns out that the conjecture is correct, but I'm looking for a mathematical explanation. Here is the code:

import math

epsilon = 2.22044604925e-14 # for integer overflow

for a in range(60):

b = 60 - a # because a+b=60

for c in range(60):

d = 60 - c

for e in range(60):

f = 60 - e

if a != b and b != c and c != d and d != e and e != f:

try:

rightHandSide = (

math.sin(math.radians(a))

* math.sin(math.radians(c))

* math.sin(math.radians(e))

) / (

math.sin(math.radians(b))

* math.sin(math.radians(d))

* math.sin(math.radians(f))

)

if abs(1 - rightHandSide) < epsilon:

print(f"a is {a}, b is {b}, c is {c}, d is {d}, e is {e}, f is {f}")

except ZeroDivisionError:

pass

The Python output for the code (of course, most of these results are the same triangles, just rotated):

a is 6, b is 54, c is 42, d is 18, e is 48, f is 12

a is 6, b is 54, c is 48, d is 12, e is 42, f is 18

a is 12, b is 48, c is 18, d is 42, e is 54, f is 6

a is 12, b is 48, c is 54, d is 6, e is 18, f is 42

a is 18, b is 42, c is 12, d is 48, e is 54, f is 6

a is 18, b is 42, c is 54, d is 6, e is 12, f is 48

a is 42, b is 18, c is 6, d is 54, e is 48, f is 12

a is 42, b is 18, c is 48, d is 12, e is 6, f is 54

a is 48, b is 12, c is 6, d is 54, e is 42, f is 18

a is 48, b is 12, c is 42, d is 18, e is 6, f is 54

a is 54, b is 6, c is 12, d is 48, e is 18, f is 42

a is 54, b is 6, c is 18, d is 42, e is 12, f is 48

Thanks in advance for any sort of help or contribution.