Your question is interesting, but it boils down to the property of $x^x$.

You can derive from your inequality an implicit form $y^x \ln^y(x)-x^x$, $y=5$, $x=2$ and simply try to solve by $y$ this equality, $y^x\ln^y(x)-x^x=0$

This equation surprisingly has a closed form solution $y=\frac{x\,W(\ln(\ln(x)))}{\ln(\ln(x))}$ where $W$ is Lambert function, an inversion of $We^W=z$. Now simply:

$$\frac{W(\ln(\ln(2)))}{\ln(\ln(2))} \approx 2.4997... < \frac{5}{2}$$

This is the reason for your inequality.

On the other hand the solution of

$$\frac{W(\ln(\ln(x)))}{\ln(\ln(x))} = \frac{5}{2}$$ is $x=e^{(\frac{2}{5})^\frac{2}{5}} \approx 1.999 < 2$ again fits your inequality

From here you can see that any proof is nothing more than computation exercise and probably the simplest one is to take first few digits of $\ln(2)$ and raise it to fifth power. Lambert function is an object of its own, and if you attach it to something like $\ln(\ln(2))$ you have to expect employing some highly precise technique.

This is the entire and the shortest proof:

$$ (ln(2) \cdot 10^6)^5 > 693145^5=160000181024126357095762965625>0.16 \cdot 10^{30} = (\frac{2}{5})^2 \cdot 10^{30}$$

Interesting part is to explain the reason we have so close match in the first place. One of the interesting equivalent forms is $f(x)=e^{(\frac{1}{x})^\frac{1}{x}}-2$ We want to know what is happening around $f(\frac{5}{2})$

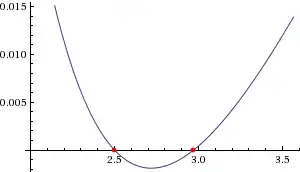

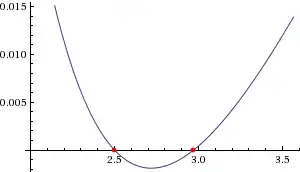

$f(x)=e^{(\frac{1}{x})^\frac{1}{x}}-2$ has the minimum at $e^{(1/e)^{1/e}}-2$ at $x=e$. One of the two zeros is at $x=\frac{W(\ln(\ln(2)))}{\ln(\ln(2))}$ which means $f(\frac{5}{2})<0$

Still, this does not explain the closeness of the zero itself to 2.5. Let us look back to $y=\frac{x\,W(\ln(\ln(x)))}{\ln(\ln(x))}$

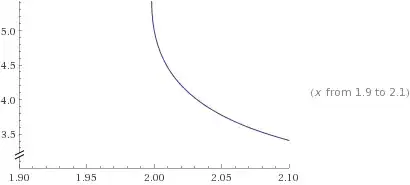

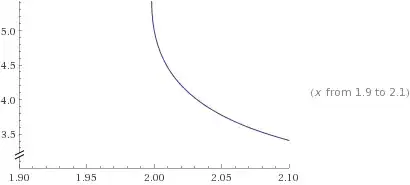

The reason the point $x=2,y=5$ is so close to the curve $y=\frac{x\,W(\ln(\ln(x)))}{\ln(\ln(x))}$ is that the function is almost vertical around 2.

After some not so difficult calculations you can find that the first derivative of $y=\frac{x\,W(\ln(\ln(x)))}{\ln(\ln(x))}$ has one of the factors as $\frac{1}{W(\ln(\ln(x))) + 1}$ and this is the key point since $W(\ln(\ln(x)))=-1$ has the solution $x=e^{(1/e)^{1/e}}$ which is as we have shown smaller than but very close to 2.

We have $y(e^{(1/e)^{1/e}})=e \cdot e^{(1/e)^{1/e}} \approx 5.43...$ Since the function is almost vertical around 2, this means that moving from 5.43 to 5 we would still remain close to 2.

In essence, a really technically complete proof requires to find a good estimation for

$$\frac{e \cdot e^{(\frac{1}{e})^{\frac{1}{e}} }-5}{2-e^{(\frac{1}{e})^{\frac{1}{e}}}}$$

and to prove that this is larger than the average slope for $y=\frac{x\,W(\ln(\ln(x)))}{\ln(\ln(x))}$ in the interesting region. This would mean that we could not reach 2 going from $e^{(1/e)^{1/e}}$ down the slope.

However, this or any similar method would require the precision that is definitely higher than purely calculating six-digit fifth power, but it is interesting to reveal the magic behind the inequality nevertheless.

$$\int_0^1 \frac{5\log^4(1+x)}{1+x}dx = \log^5(2) \approx 0.1600027$$

– Jaume Oliver Lafont Apr 15 '16 at 08:00