$$\color{brown}{\mathbf{Preliminary\ notes.}}$$

If $\underline{\gcd(m,n)=g\not=1}$ then $\min\limits_{k,l}\, d(gm_1,gn_1,k,l) = \underline{(d(m_1,n_1,k_1,l_1)-l_1)g + l_1)}.$

If $\underline{n=1}$ then $\min\limits_{k,l}\, d(m,n,k,l) = \underline{n+1}\ $ at $(k,l)=(k_0,l_0) = (0,\pm1).$

If $\underline{n=m-1}$ then $\min\limits_{k,l}\, d(m,n,k,l) = \underline{2}\ $ at $(k,l)=(k_0,l_0) = (-1,1).$

If $\underline{n\in[2,m-2]}$ then WLOG

$$\gcd(m,n) = 1,\ l\ge 0,\ k<0,\ \gcd(k,l)=1,\tag1$$

$$D_{m,n}=\min\limits_{k,l}\ d(m,n,k,l)

=\min\limits_{k,l}\,\max\left|(m,n\pm1)\cdot(k,l)\large\mathstrut\right|.\tag2$$

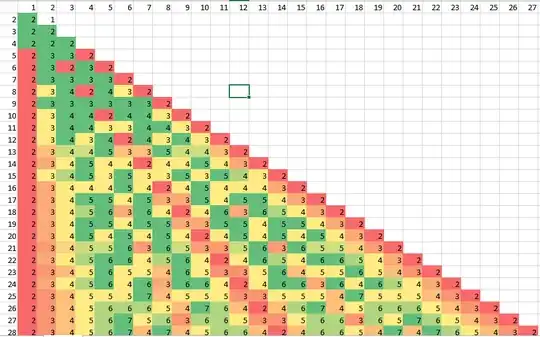

Formulas $(2)$ allows to calculate $D_{m,n}$ immediately, using the tables.

If $\underline{(m,n)=(7,3)}:$

$\left[\begin{matrix}

\mathbf{(7,3)} & (-1,1) & (-1,2) & (-1,3) & (-2,3) & (-2,5)\\

(7,2) & 5 & 3 & 1 & 8 & 4 \\

(7,4) & 3 & 1 & 5 & 2 & 6 \\

\textbf{max} & 5 & \mathbf3 & 5 & 8 & 6 \\

\end{matrix}\right]$

If $\underline{(m,n)=(3,2)}:$

$\left[\begin{matrix}

\mathbf{(3,2)} & (-1,0) & (-1,1) & (-1,2) & (-2,1) & (-2,3)\\

(3,1) & 3 & 2 & 1 & 5 & 3 \\

(3,3) & 3 & 0 & 3 & 3 & 0\\

\textbf{max} & 3 & \mathbf2 & 3 & 5 & 3\\

\end{matrix}\right]$

$$\color{brown}{\mathbf{Estimations.}}$$

Proposed task belongs to the discrete type of tasks, which exact solution in the common case can not be provided without option calculation algorithm. So universal solution of the given task in the closed form for all arbitrary unbounded values looks impossible.

However, for the bounded values of $n,$ exact solutions have closed form. Also, can be found solution for any given pair $(m,n).$

$\mathbf{Case\ k=-1.}$

Since

$$m\in n\left[f(m,n),c(m,n)\large\mathstrut\right],$$

where

$$f(m,n)=\left\lfloor\dfrac mn\right\rfloor,\quad c(m,n)=\left\lceil\dfrac mn \right\rceil.$$

This leads to the estimation

$$D_{m,n} \le \min\left\{F^{(1)}_{m,n},C^{(1)}_{m,n}\right\},$$

where

$$F^{(1)}_{m,n} = d(m,n,-1,f(m,n)),\quad C^{(1)}_{m,n} = d(m,n,-1,c(m,n)),$$

or

\begin{cases}

F^{(1)}_{m,n} = \max\left\{m-(n-1)f(m,n),(n+1)f(m,n)-m\right\},\\

C^{(1)}_{m,n} = \max\left\{m-(n-1)c(m,n),(n+1)c(m,n)-m\right\}.\tag3

\end{cases}

In particular, the values $\ f(7,3) = 2 $ and $\ f(3,2)=1\ $ lead to the optimal solutions.

$\mathbf{Case\ k>1\ (first\ iteration).}$

If $n\!\!\not|\ m,$ then

$$\dfrac mn - r_2\in\left[\cfrac 1{c(n,m-nr_2)},\cfrac 1{f(n,m-nr_2)}\right],$$

or

$$m\in n\left[\dfrac{r_2c(n,m-nr_2)+1}{c(n,m-nr_2)},\dfrac{r_2f(n,m-nr_2)+1}{f(n,q_2)}\right]$$

where

$$r_2=f(m,n).$$

This leads to the estimation

$$D_{m,n} \le \min\left\{F^{(2)}_{m,n},C^{(2)}_{m,n}\right\},$$

where

$$F^{(2)}_{m,n} = d(m,n,-k^{(2)}_f,r_2k^{(2)}_f+1),

\quad C^{(2)}_{m,n} = d(m,n,-k^{(2)}_c,r_2k^{(2)}_c+1),\tag4$$

$$k^{(2)}_f = \left\lfloor\dfrac n{m-nr_2}\right\rfloor,

\quad k^{(2)}_c = \left\lceil\dfrac n{m-nr_2}\right\rceil.\tag5$$

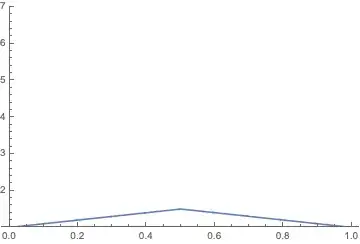

$\mathbf{Case\ k>1\ (continued\ fraction\ estimations).}$

The alternative way is using of continued fraction decomposition in the form of

$$\dfrac mn = [r^\,_{3,0};r^\,_{3,1},r^\,_{3,2},\dots,r^\,_{3,i}]

=r^\,_{3,0} + \cfrac 1{r^\,_{3,1}+\cfrac 1{r^\,_{3,2}+\cfrac 1{\dots+\cfrac 1{r^\,_{3,i-1}+\cfrac1{r^\,_{3,i}}}}}}.$$

Similarly to the previous case, this leads to the estimations

$$D_{m,n} \le \min\left\{F^{(3)}_{m,n}(j),C^{(3)}_{m,n}(j)\right\},$$

where

$$F^{(3)}_{m,n}(j) = d(m,n,-k^{(3)}_f(j),l^{(3)}_f(j)),

\quad C^{(3)}_{m,n}(j) = d(m,n,-k^{(3)}_c(j),l^{(2)}_c(j)),\tag6$$

$$\dfrac{l^{(3)}_f(j)}{k^{(3)}_f(j)} = [r^\,_{3,0};r^\,_{3,1},r^\,_{3,2},\dots,r^\,_{3,j}],

\quad \dfrac{l^{(3)}_c(j)}{k^{(3)}_c(j)} = [r^\,_{3,0};r^\,_{3,1},r^\,_{3,2},\dots,r^\,_{3,j}+1].\tag7$$

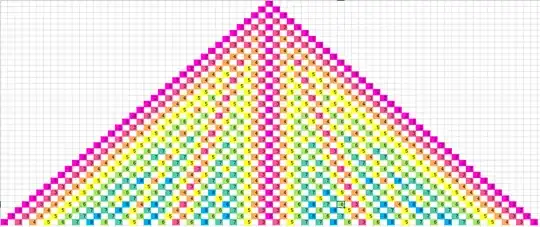

$$\color{brown}{\mathbf{Numeric\ modeling.}}$$

Let us consider the case of

$(m,n) = (F_{i+1},F_i),$

where $F$ is Fibonacchi sequence.

$${\small\left[\begin{matrix}

\mathbf{(5,3)} & (-1,1) & (-1,2) & (-2,3) & (-3,5) \\

(5,2) & 3 & 1 & 4 & 5 \\

(5,4) & 1 & 3 & 2 & 5 \\

\textbf{max} & \mathbf 3 & \mathbf3 & 4 & 8 \\

\end{matrix}\right]\

\left[\begin{matrix}

\mathbf{(8,5)} & (-1,1) & (-1,2) & (-2,3) & (-3,5) \\

(8,4) & 4 & 0 & 4 & 4 \\

(8,6) & 2 & 4 & 2 & 6 \\

\textbf{max} & \mathbf 4 & \mathbf 4 & \mathbf 4 & 6 \\

\end{matrix}\right]}

$$$$

{\small\left[\begin{matrix}

\mathbf{(13,8)} & (-1,1) & (-1,2) & (-2,3) & (-3,5) \\

(13,7) & 6 & 1 & 5 & 4 \\

(13,9) & 4 & 5 & 1 & 6 \\

\textbf{max} & 6 & \mathbf5 & \mathbf5 & 8 \\

\end{matrix}\right]\

\left[\begin{matrix}

\mathbf{(21,13)} & (-1,1) & (-1,2) & (-2,3) & (-3,5) \\

(21,12) & 9 & 3 & 6 & 3 \\

(21,14) & 7 & 7 & 0 & 7 \\

\textbf{max} & 9 & 7 & \mathbf 6 & 7 \\

\end{matrix}\right]}

$$$$

{\small\left[\begin{matrix}

\mathbf{(34,21)} & (-1,2) & (-2,3) & (-3,5) & (-5,8)\\

(34,20) & 6 & 8 & 2 & 10\\

(34,22) & 10 & 2 & 8 & 6\\

\textbf{max} & 10 & \mathbf 8 & \mathbf 8 & 10\\

\end{matrix}\right]

\left[\begin{matrix}

\mathbf{(55,34)} & (-1,2) & (-2,3) & (-3,5) & (-5,8)\\

(55,33) & 11 & 11 & 0 & 11\\

(55,35) & 20 & 5 & 10 & 5\\

\textbf{max} & 20 & 11 & \mathbf{10} & 11\\

\end{matrix}\right]}$$

Considered example illustrates that for $n>30$ simple models does not lead to exact solutions in the common case.

Taking in account unknown behavior of continued fraction approximations, existing of the common solution of the given task in the closed form looks impossible.

On the other hand, calculations of the optimal solution in the common case have logarithmic complexity by the value of m, because $2\log_5 m$ is a high bound of the length of the continued fraction sequence.