Consider three events $A,B,C$ such that $P(A)>0$, $P(B)>0$, and $P(C)>0$. The events are dependent to each other through the constraints $P(A\cup B\cup C) = 1$ and $P(A)=P(\overline{B})$. Under these conditions, I have to study the probability of the event $A\cap B\cap C$. By means of Bayes' theorem, I have obtained the following relation: $$ P(A\cap B\cap C)=\frac{P(A\cap B\cap C|B)P(A\cap B\cap C|A)}{P(A\cap B\cap C|B)+P(A\cap B\cap C|A)}. $$

In fact, being $I=A\cap B\cap C$, we have $P(I|A)P(A)=P(A|I)P(I)$ and $P(I|B)P(B)=P(B|I)P(I)$. Clearly, $P(A|I)=P(B|I)=1$. Therefore, applying the definition of opposite event $P(\overline{B})=1-P(B)$, and assuming $P(I|A)>0$, $P(I|B)>0$, we have $P(A)=\frac{P(I)}{P(I|A)}$ and $P(\overline{B})=1-\frac{P(I)}{P(I|B)}$. Equaling these two expressions (in which, however, I did not use the constraint $P(A\cup B\cup C)=1$) we obtain the above, highlighted relation.

On the other hand, by means of the principle of inclusion-exclusion, I have also found that $$ P(A\cap B\cap C)=P(A\cap B)+P(A\cap C)+P(B\cap C)-P(C). $$

In fact, $$P(A\cup B\cup C)=P(A)+P(B)+P(C)-P(A\cap B)-P(B\cap C)-P(A\cap C)+P(A\cap B\cap C),$$ and $$ P(A\cap B\cap C)=\underbrace{P(A\cup B\cup C)}_{=1}-P(A)-P(B)-P(C)+P(A\cap B)+P(B\cap C)+P(A\cap C). $$ If we substitute the other constraint $P(A)=P(\overline{B})$, or $1-P(B)-P(A)=0$, in this expression, we obtain the second highlighted relation.

My question is this:###

From the first relation, it seems that $P(A\cap B\cap C)$ depends only on the knowledge of the occurrence of $A$ and $B$, but the second one seems to assess an explicit dependence of $P(A\cap B\cap C)$ from $P(C)$. What's wrong here?

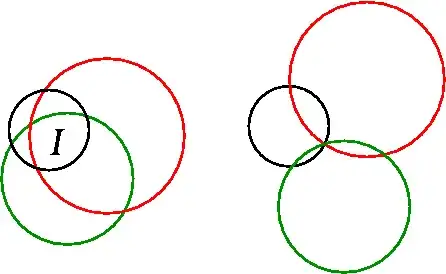

My suspect is illustrated in this picture, where the three events are depicted as sets of different colors:

I wonder if the two constraints are moving the situation on the left to the one on the right, in which $P(I)=P(A\cap B\cap C)=0$. Somehow, it seems to me that the constraint I did not use to get the first relation (i.e. $P(A\cup B\cup C)=1$) requires $P(I)=0$ therein.

Therefore, $P(A \cap C) = P(C)$

– Ben Crossley Jun 20 '18 at 21:42which is in fact a is way to express the dependence of the RHS of C.

– Boyku Jun 21 '18 at 09:20