The question really is in the title. I know what it means if the dot product equals 0 but I find it interesting thinking what it means when it equals exactly 1 and can't seem to find anything online to enlighten me.

Thanks

The question really is in the title. I know what it means if the dot product equals 0 but I find it interesting thinking what it means when it equals exactly 1 and can't seem to find anything online to enlighten me.

Thanks

I'm really surprised this question still doesn't have a complete answer.

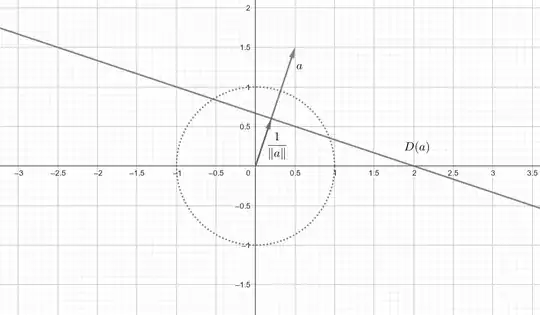

Given any vector $a \in \mathbb{R}^2 \setminus \{0\}$, the set $$D(a) = \left\{x \in \mathbb{R}^2 \mid \left\langle a,x \right\rangle=1\right\}$$ looks like this:

$D(a)$ is a line with distance $\frac{1}{\|a\|}$ from the origin perpendicular to $a$.

If you move $a$ to the unit circle (indicated with a dotted line), $D(a)$ will be tangent to the unit circle at $a$. If you know that $x$ is pointing in the same direction as $a$, you can see it has length $\frac{1}{\|a\|}$, as indicated by the other answers.

In the context of discrete geometry, $D(a)$ is also called the Duality Transform of $a$, which makes it a bit tricky to look up, since the concept of duality is everywhere in mathematics. I can't seem to find this term in online sources, but this is what it's called in academic textbooks.

So, to answer the question: if you know two vectors $a$ and $b$ have a dot product of $1$, you know that $b$ is somewhere in the Duality Transform of $a$, and - since the dot product is commutative - that $a$ is in the Duality Transform of $b$.

Side note: this concept generalizes to any dimension. In $\mathbb{R}^3$, $D(a)$ will be a plane with normal vector $a$ and distance $\frac{1}{\|a\|}$ from the origin.

If you already know the vectors are both normalized (of length one), then the dot product equaling one means that the vectors are pointing in the same direction (which also means they're equal).

If you already know the vectors are pointing in the same direction, then the dot product equaling one means that the vector lengths are reciprocals of each other (vector b has its length as 1 divided by a's length). For example, 2D vectors of (2, 0) and (0.5, 0) have a dot product of 2 * 0.5 + 0 * 0 which is 1. Also, (1, 1) has a length of sqrt(2), and (0.5, 0.5) has a length of 1/sqrt(2), and the dot product is also 1.

If you don't already know anything about the vectors, you can't concretely say anything about this.

Unless the vectors are normalized or the context is a geometric inversion, the dot product being equal to $1$ is essentially coincidental and has no useful meaning.

If they are normalized, then they are parallel. $-1$ for antiparallel.