The first expression can be seen as the product of a $2\times2$ matrix by the vector $(\sin\theta,\cos\theta)$.

By the Eigen decomposition theorem, the matrix can be decomposed in the product of

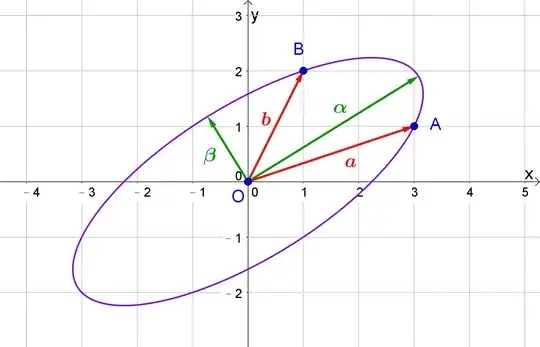

- a rotation (of angle $\alpha$),

- an anisotropic scaling along the coordinate axis,

- the counter-rotation (of angle $-\alpha$).

The first rotation transforms the vector $(\sin\theta,\cos\theta)$ into $(\sin(\theta+\alpha),\cos(\theta+\alpha))$. The scaling makes a linear combination of two orthogonal vectors of lengths $\|a\|$ and $\|b\|$, hence $(\|a\|\sin(\theta+\alpha),\|b\|\cos(\theta+\alpha))$. The counter rotation gives a new direction to these vectors.

So $\alpha$ corresponds to the directions of the Eigenvectors, which are also the directions of $\mathbf a$ and $\mathbf b$, and the lengths of these vectors are the Eigenvalues.

Alternatively:

Using the angle addition formulas, the two representations are linear combinations of the sine and cosine of $\theta$.

The vectors $\mathbf A$ and $\mathbf B$ carry four degrees of freedom. The vectors $\mathbf a$ and $\mathbf b$ are lacking one, as they are constrained to be orthogonal; but the missing degree of freedom is now supported by the parameter $\alpha$.