The Hilbert curve has always bugged me because it had no closed equation or function that I could find. What is its equation or function? For example, if I wanted to find the Hilbert's curve point at 4/7, how would I find it?

-

Since the Hilbert curve covers (for example) the unit square, then it is the zero set of the characteristic function of the complement of that square: this gives you the equation... – Mariano Suárez-Álvarez Sep 07 '14 at 00:59

-

1@MarianoSuárez-Alvarez I know it's been two years, but would you be willing to give a more detailed answer than this comment? This is a very high level explanation of the Hillbert curve and it's still not obvious what the closed-form expression for the hilbert curve at a point 4/7 (asker's example). – Axoren Feb 24 '16 at 04:44

-

1@Axoren: I think Mariano was being somewhat facetious. Some people vastly prefer to consider a curve as its image, and not tied to any particular parametrization. Some other people refer to a specific parametrization when they speak of a curve. Mariano wrote his comment assuming the former, the question was originally asked assuming the latter. – Willie Wong Apr 12 '16 at 13:21

-

I have also wondered about this. May I just ask – did you have any application in mind when you came up with the question, for which you wanted to know the answer? (I don't remember whether I had any specific application in mind myself, but I probably did) – HelloGoodbye Mar 17 '18 at 22:47

-

@HelloGoodbye nah, although 3b1b had one. – Christopher King Mar 17 '18 at 22:48

-

1Hm, maybe that 3blue1brown video is where I got the question from too; thanks. – HelloGoodbye Mar 18 '18 at 02:31

2 Answers

As pointed out in this other answer, there is a formula for Hilbert's space filling curve in Space-Filling Curves by Hans Sagan. The formula below appears as formula 2.4.3 on page 18 of the text.

If we first write $t\in[0,1)$ in its base four expansion, $$t=0_{\dot 4}q_1q_2q_3\ldots,$$ then $$h(t) = \sum_{j=1}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^{e_{0j}}}{2^j}\text{sign}(q_j) \left( \begin{array}{c} (1-d_j)q_j - 1 \\ 1-d_jq_j \end{array} \right), $$ where $e_{kj}$ denotes the number of $k$s preceding $q_j$ and $d_j=e_{0j}+e_{3j} \mod 2$ and $\text{sign}(x)$ is $1$ if $x$ is positive, $0$ if $x$ is zero and $-1$ if $x$ is negative (though $q_j$ is never negative).

While it takes a bit to digest, it's not too outrageously complicated and quite easy to program. If the denominator of $t$ is a power of 2, then the base four expansion will terminate and the computation is exact. For any other rational number, the base four expansion is periodic and the value can still be computed exactly using a geometric series. For irrational numbers, the sum can be truncated to obtain a good decimal approximation.

Consider, for example, your question about $t=4/7$. We have the base four expansion $$\frac{4}{7} = 0_{\dot 4}\overline{210}.$$ Now, $$ h(0_{\dot 4}210) = \left( \begin{array}{c} 1/2 \\ 1/2 \\ \end{array} \right) + \left( \begin{array}{c} 0 \\ 1/4 \\ \end{array} \right) + \left( \begin{array}{c} 0 \\ 0 \\ \end{array} \right) = \left( \begin{array}{c} 1/2 \\ 3/4 \\ \end{array} \right), $$ $$ h(0_{\dot 4}000210) = \left( \begin{array}{c} 1/16 \\ 1/16 \\ \end{array} \right) + \left( \begin{array}{c} 1/32 \\ 0 \\ \end{array} \right) + \left( \begin{array}{c} 0 \\ 0 \\ \end{array} \right) = \left( \begin{array}{c} 3/32 \\ 1/16 \\ \end{array} \right), $$ $$ h(0_{\dot 4}000000210) = \left( \begin{array}{c} 1/128 \\ 1/128 \\ \end{array} \right) + \left( \begin{array}{c} 0 \\ 1/256 \\ \end{array} \right) + \left( \begin{array}{c} 0 \\ 0 \\ \end{array} \right) = \left( \begin{array}{c} 1/128 \\ 3/256 \\ \end{array} \right), $$ and $$ h(0_{\dot 4}000000000210) = \left( \begin{array}{c} 1/1024 \\ 1/1024 \\ \end{array} \right) + \left( \begin{array}{c} 1/2048 \\ 0 \\ \end{array} \right) + \left( \begin{array}{c} 0 \\ 0 \\ \end{array} \right) = \left( \begin{array}{c} 3/2048 \\ 1/1024 \\ \end{array} \right). $$ Looking at the columns, it's not too hard to spot the pattern and we have $$ h(4/7) = \left( \begin{array}{c} 1/2 \\ 1/2 \\ \end{array} \right) \sum _{k=0}^{\infty } \frac{1}{8^k}+\left( \begin{array}{c} 1/32 \\ 1/4 \\ \end{array} \right) \sum _{k=0}^{\infty } \frac{1}{64^k} = \left( \begin{array}{c} 38/63 \\ 52/63 \\ \end{array} \right). $$

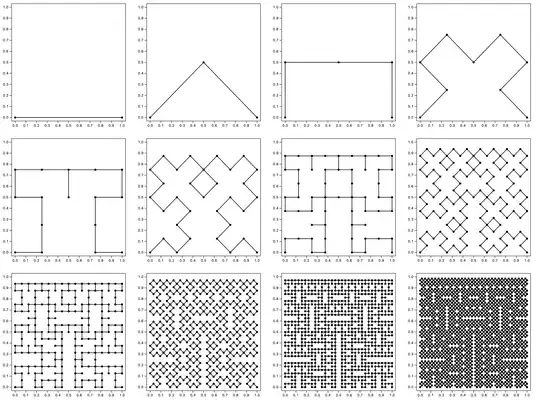

Finally, here are some approximations to Hilbert's curve obtained by passing a polygonal curve the points $h(p/2^k)$ for increasing values of $k$.

The code to produce this image can be found in this Observable notebook.

- 31,496

-

1

-

1@user678510 this is late, but if anybody else is wondering: I'd assume it's like the "signum" function found in many programming languages; return 1 if x>0, -1 if x<0, 0 if x=0 – coolreader18 May 19 '21 at 16:47

-

@coolreader18 That's correct. In the book, there's an implementation of this in IBM BASIC using the SGN function. Of course, in this particular case, the value passed to sign is never negative, so this just means to skip the term if $q_j$ is zero. – John Gowers Jan 10 '22 at 14:39

-

What syntax is $\frac{4}{7} = 0_{\dot 4}\overline{210}$? I have never seen it before. – HelloGoodbye Oct 15 '23 at 23:33

The expression is fairly complicated and the derivation fairly tricky. Look it up in Hans Sagan, Space-filling curves, Springer 1994.

- 18,650