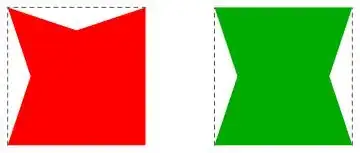

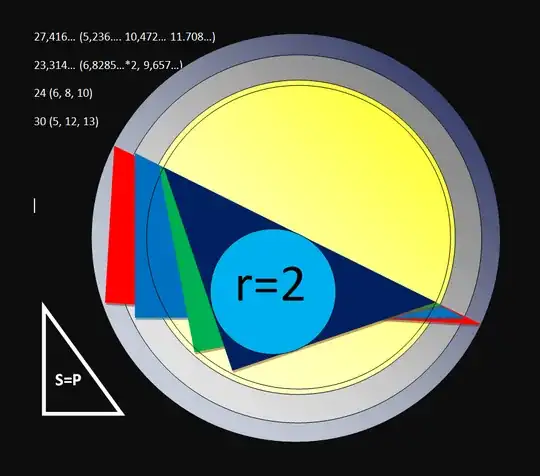

The figure is a visual representation of four different possible right triangles satisfying the equality S=P

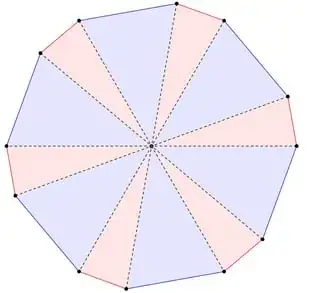

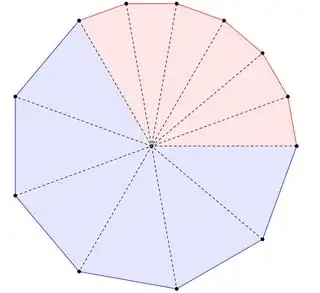

According to the results of calculations, the following numerical equalities of the area and perimeter of a number of two-dimensional figures were revealed:

– of a square, when the side is 4 (the area and length of the perimeter, respectively, will be equal to the value 16), the radius of the inscribed circle is 2, and the described one is equal to the value 8, the diagonal of the square is equal to 32;

– a circle, when the equality of the area and the length of the circle is observed at a value of 12.566 ... or 4 π (the radius of the inscribed circle is 2);

– right-angled triangles with an irrational value of area and perimeter, when the area and length of the perimeter of the first is equal to the value 27,4163... ≡(√5+3)2 ( where the smaller catheter is 5,236... will be equal to √27.4163... or ≡√5+3, and the larger one is twice the value of the smaller one - 10.472 ..., the hypotenuse is 11.7082≡√45+5); the second, when the catheters are 6.8285... ≡√8+4, and the hypotenuse is 9.6568≡√32+4 with an area and perimeter value of 23.314... ≡(√8+2)2. The radius of the circle inscribed in the triangle is 2;

– Heron triangles with sides: (5, 12, 13 and 6, 8, 10 are right–angled triangles) when the area and perimeter of the first is equal to the value of 30, and the second - 24; 6, 25, 29; 7, 15, 20; 9, 10, 17 ... ( obtuse triangles with an area of and the perimeter are equal to 60, 42, 36, respectively), the radius of the circle inscribed in the named triangles is 2;

– an equilateral right triangle, with an area value of 20.7846... or =√3×12 (while the side length is 6.928...≡√48 or =√3×4), the radius of the inscribed circle is 2.

According to the results of calculations, the following numerical equalities of volume and area of a number of three-dimensional figures were revealed:

– a cube with a face equal to the value of √8, the volume and surface area of the cube is 216, the radius of the inscribed sphere is 3;

– spheres (equality of volume and surface area) equal to the value 113.097335526... or 36 π (in this case, the diameter of the sphere is 6, and its circumference is 18.85...≡6 π), the radius of the inscribed sphere is 3;

– tetrahedron (equality of area and volume) equal to 374,123... ≡216×√3 (while the edge length is 14.669693845669907...≡√216), the radius of the inscribed sphere is 3;

– octahedron (equality of area and volume) equal to the value 187.061... ≡108×√3 (while the edge length is 7.348669228349534...≡√54), the radius of the inscribed sphere is 3;

– icosahedron (equality of area and volume) equal to the value 136.4595... (while the edge length is 3.9695...), the radius of the inscribed sphere is 3;

– dodecahedron (equality of area and volume) equal to the value 149.8578... (while the edge length is 2.694168...), the radius of the inscribed sphere is 3;

– cylinder (equality of area and volume) equal to the value 54π ≈ 169.646 ... (in this case, the radius is 3, and the height is double the value of the radius – 6). The area of the side surface is 113.097 ... (volume and area of the sphere inscribed in the figure) or 36π, and the area of one of the two bases is 9π, the radius of the inscribed The volume of the cylinder is equal to 3. The volume of the cylinder is exactly 1.5 times greater than the volume of the sphere inscribed in it (where there is equality of area and volume values);

– a cone (equality of area and volume) equal to the value 96π ≈ 301.593... (in this case, the radius of the base is 6, the forming area is 10, and the height of the figure is 8). The area of the base (circle) is 113.097 ... (volume and area of the sphere inscribed in the figure) or 36π, the area of the lateral surface, respectively, – 60π, the radius of the inscribed sphere is 3;

– a triangular pyramid (equality of area and volume of a tetrahedron) at a height of 12, the side of the base is 14.66969384567...≡√216 and is equal to the value 374.123..., the radius of the inscribed sphere is 3;

– a four–sided pyramid (equality of area and volume) with a height of 12, the side of the base is 8.485281374...≡√72 and is equal to 288. The ratio of height to the side of the base is √2. At the same time, the area of the side surface of the pyramid is three times the area of the base (216 and 72), the radius of the inscribed sphere is 3;

– a hexagonal pyramid with a height of 12, the side of the base is 4,898979485...≡√24 and is equal to 249.415..., the radius of the inscribed sphere is 3.

Based on the calculations carried out, the conclusion is formulated:

– in two-dimensional figures: square, circle, rectangular, obtuse and equilateral triangles, the radius of the inscribed circle with equal values of area and perimeter is 2;

– in three-dimensional figures, tetrahedron, cube, octahedron, icosahedron, dodecahedron, cone, cylinder, 3-4-6-sided pyramid and sphere, the radius of the inscribed circle with equal values of area and volume is 3.