Let $\mathbb{K} \in \{\mathbb{R}, \mathbb{C}\}$ be either the set of real number $\mathbb{R}$ or the set of complex numbers $\mathbb{C}$ (with their respective algebra).

Definition (Standard inner product on $\mathbb{K}^n$).

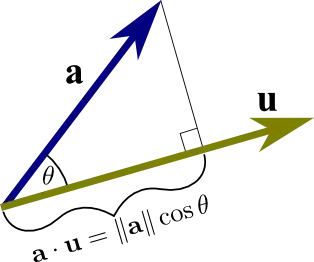

The standard inner product between two vectors $\mathbf{x},\mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{K}^n$ is the scalar

\begin{equation}

\langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y} \rangle = \mathbf{x}^* \mathbf{y} = \sum_{i=1}^n \overline{x}_i y_i,

\end{equation}

where $\bullet^*$ denotes the the conjugate transpose and $\overline{\bullet}$ the complex conjugate. In particular, for $\mathbf{x},\mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^n$, we have

\begin{equation}

\langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y} \rangle = \mathbf{x}^\mathrm{T} \mathbf{y} = \sum_{i=1}^n x_i y_i.

\end{equation}

Definition (Standard norm on $\mathbb{K}^n$). The standard norm on $\mathbb{K}^n$ is the norm induced by the standard inner product on $\mathbb{K}^n$, i.e. $\Vert{\mathbf{x}}\Vert := \langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x} \rangle^{\tfrac{1}{2}}$.

Definition (Orthogonal projection). The orthogonal projection of a vector $\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^n$ onto the subspace $\mathrm{span}(\mathbf{e}_i)_{i=1}^n$ spanned by the orthonormal vectors $(\mathbf{e}_i)_{i=1}^m$, with

\begin{equation}

\langle \mathbf{e}_i, \mathbf{e}_j \rangle

= \delta_{ij}

:=

\begin{cases}

1 & i = j \\

0 & \text{otherwise}

\end{cases},

\end{equation}

is the vector

\begin{equation}

\underset{\mathrm{span}(\mathbf{e}_i)_{i=1}^m}{\mathrm{proj}} \mathbf{x} := \sum_{i=1}^m \langle \mathbf{a}_i, \mathbf{e}_i \rangle \mathbf{e}_i.

\end{equation}

Proposition (Complement). For some vector $\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^n$ and an orthonormal system $(\mathbf{e}_i)_{i=1}^m$, if

\begin{equation}

\hat{\mathbf{x}} = \underset{\mathrm{span}(\mathbf{e}_i)_{i=1}^m}{\mathrm{proj}} \mathbf{x},

\end{equation}

then, for any vector $\mathbf{y} \in \mathrm{span}(\mathbf{e}_i)_{i=1}^m$, we have

\begin{equation}

\langle \mathbf{x} - \hat{\mathbf{x}}, \mathbf{y} \rangle = 0.

\end{equation}

Proof. As $\mathbf{y} \in \mathrm{span}(\mathbf{e}_i)_{i=1}^m$, we have

\begin{equation}

\mathbf{y} = \sum_{i=1}^m \langle \mathbf{y}, \mathbf{e}_i \rangle \mathbf{e}_i,

\end{equation}

so

\begin{equation}

\langle \hat{\mathbf{x}}, \mathbf{y} \rangle = \langle \sum_{i=1}^m \langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{e}_i \rangle \mathbf{e}_i, \mathbf{y} \rangle = \sum_{i=1}^m \langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{e}_i \rangle \langle \mathbf{y}, \mathbf{e}_i \rangle = \langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y} \rangle. \qquad \square

\end{equation}

Proposition (Gram-Schmidt) Let $(\mathbf{a}_i)_{i=1}^n$ be a basis for $\mathbb{K}^n$. Define the system $(\mathbf{e}_i)_{i=1}^n$ recursively by the Gram-Schmidt procedure,

\begin{equation}

\mathbf{u}_1 := \mathbf{a}_1, \qquad \mathbf{e}_1 := \frac{\mathbf{u}_1}{\Vert \mathbf{u}_1 \Vert}

\end{equation}

and

\begin{equation}

\mathbf{u}_j := \mathbf{a}_j - \underset{\mathrm{span}(\mathbf{e}_k)_{k=1}^{j-1}}{\mathrm{proj}} \mathbf{a}_j, \qquad \mathbf{e}_j := \frac{\mathbf{u}_j}{\Vert \mathbf{u}_j \Vert} \qquad (\,{j=2,3,\ldots,n}\,).

\end{equation}

Then, $(\mathbf{e}_i)_{i=1}^n$ is an orthonormal system and

\begin{equation}

\mathrm{span}(\mathbf{e}_i)_{i=1}^m = \mathrm{span}(\mathbf{a}_i)_{i=1}^m \qquad {(\,m=1,2,\ldots,n\,)},

\end{equation}

and in particular $\mathbb{K}^n = \mathrm{span}(\mathbf{a}_i)_{i=1}^n = \mathrm{span}(\mathbf{e}_i)_{i=1}^n$ so $(\mathbf{e}_i)_{i=1}^n$ is an orthonormal basis for $\mathbb{K}^n$.

Proof. We wish to show that, during the Gram-Schmidt process, we do not divide by zero and that the procedure arrives at the desired orthonormal system.

Let $(\mathbf{a}_i)_{i=1}^n$ be a basis for $\mathbb{K}^n$. We proceed by induction on the size $m = 1,2,\ldots,n$ of the subsystem $(\mathbf{a}_i)_{i=1}^m$.

( Base case ) Consider the subsystem $(\mathbf{a}_i)_{i=1}^n = (\mathbf{a}_1)$ of size $m=1$. All vectors in $(\mathbf{a}_i)_{i=1}^n$ are non-zero, otherwise $(\mathbf{a}_i)_{i=1}^n$ would not be linearly independent. Hence, $\mathbf{u}_1 := \mathbf{a}_1 \neq \mathbf{0}$, the norm $\Vert \mathbf{u}_1 \Vert \neq 0$, and we can divide $\mathbf{u}_1$ by its norm to get $\mathbf{e}_1 := \frac{\mathbf{u}_1}{\Vert \mathbf{u}_1 \Vert}$. The system $(\mathbf{e}_1) = (\mathbf{e}_1)_{i=1}^1$ is trivially orthonormal and $\mathrm{span}(\mathbf{a}_1) = \mathrm{span}(\mathbf{u}_1) = \mathrm{span}(\mathbf{e}_1)$.

( Induction hypothesis ) Suppose that, for some subsystem $(\mathbf{a}_j)_{j=1}^{m}$ of size $m = 1,2,\ldots,n-1$, we have that the corresponding system $(\mathbf{e}_j)_{j=1}^m$ is orthonormal and that $\mathrm{span}(\mathbf{e}_j)_{j=1}^{m} = \mathrm{span}(\mathbf{a}_j)_{j=1}^{m}$.

( Induction step ) Consider the next system $(\mathbf{a}_j)_{j=1}^{m+1}$. By definition,

\begin{equation}

\mathbf{u}_{m+1} = \mathbf{a}_{m+1} - \underset{\mathrm{span}(\mathbf{e}_k)_{k=1}^{m}}{\mathrm{proj}} \mathbf{a}_{m+1}.

\end{equation}

Suppose towards a contradiction that $\mathbf{u}_{m+1} = \mathbf{0}$, and we cannot divide by $\Vert \mathbf{u}_{m+1} \Vert$. Then,

\begin{equation}

\mathbf{u}_{m+1} = \mathbf{0} \quad \implies \quad \mathbf{a}_{m+1} = \underset{\mathrm{span}(\mathbf{e}_k)_{k=1}^{m}}{\mathrm{proj}} \mathbf{a}_{m+1} \in \mathrm{span}(\mathbf{e}_k)_{k=1}^m = \mathrm{span}(\mathbf{a}_k)_{k=1}^m,

\end{equation}

which contradicts our assumption that $(\mathbf{a}_k)_{k=1}^{m+1}$ is linearly independent. Hence, $\mathbf{u}_{m+1} \neq \mathbf{0}$, and $\mathbf{e}_{m+1} = \frac{\mathbf{u}_{m+1}}{\Vert \mathbf{u}_{m+1}\Vert} $ is well-defined. By the proposition above, we have

\begin{equation}

\langle \mathbf{u}_{m+1}, \mathbf{u}_j \rangle = \mathbf{0} \qquad (\,j=1,2,\ldots,m\,)

\end{equation}

so

\begin{equation}

\langle \mathbf{e}_{i}, \mathbf{e}_j \rangle = \frac{1}{\Vert \mathbf{u}_{i} \Vert \Vert \mathbf{u}_j \Vert} \langle \mathbf{u}_{i}, \mathbf{u}_j \rangle = \delta_{ij} \qquad (\,j=1,2,\ldots,m\,),

\end{equation}

and $(\mathbf{e}_j)_{j=1}^{m+1}$ is an orthonormal system. Furthermore,

\begin{equation}

\mathrm{span}(\mathbf{e}_i)_{i=1}^{m+1} = \mathrm{span}(\mathbf{u}_i)_{i=1}^{m+1} = \mathrm{span}(\mathbf{u}_1,\mathbf{u}_2,\ldots,\mathbf{u}_{m}, \mathbf{u}_{m+1}) = \mathrm{span}(\mathbf{a}_1,\mathbf{a}_2,\ldots,\mathbf{a}_m,\mathbf{a}_{m+1}-\mathrm{proj}\,\mathbf{a}_{m+1}) = \mathrm{span}(\mathbf{a}_i)_{i=1}^{m+1}.

\end{equation}

( Conclusion ) By induction, we have shown that the Gram-Schmidt procedure does not produce division by zero, and that it yields the desired orthonormal system $(\mathbf{e}_i)_{i=1}^n$. $\qquad \square$