$\Delta x$, $\delta x$ and $dx$ are used when talking about slopes and derivatives. But I don't know what the exact difference is between them.

-

Well, $\delta x$ means different things depending on the context. For example, it has a particular meaning in variational calculus, and a completely different one in functional calculus... – Alex Nelson Dec 27 '13 at 15:20

-

What is more instructive is to note the "shifting effect" when $\nabla$ dot-products $\delta$, like $\nabla U\cdot \delta \vec{r}=\delta U$. – MathArt Jul 01 '22 at 12:16

-

$∆x~$ is small change in $~x~$. $~dx~$ is small part of $~x~$ but represents independent change. & $~\frac{dy}{dx}~$ means slope of tangent at a point where it touches to the curve $~\frac{∆y}{∆x}~$ s the slope through two points. We say $~∆x~$ tends to zero . It becomes $~\frac{dy}{dx}~$ which is slope of tangent at a point (reason of why $~∆x~$ tends to zero). That is it – MUDDSAR YASEEN MALIK Jul 14 '19 at 12:49

5 Answers

$\Delta x$ is about a secant line, a line between two points representing the rate of change between those two points. That's a "differential" (between the two points).

$dx$ is about a tangent line to one point, representing an instantaneous rate of change. That makes it a "derivative."

$\delta x$ is about a tangent line to a partial derivative. That's a rate of change or derivative in one direction, holding a number of other directions constant.

-

3Note that in physics $\Delta x$ is also used informally to mean "small increment in $x$". And $\delta x$ can also mean a variation of a function, in the calculus of variations. I guess my point is that calculus notation is still far from standardized, and you will often need to infer the meaning of notation from the context. – user7530 Dec 27 '13 at 16:50

-

1@user7530 My experience is that $\Delta x$ denotes the difference, or change of $x$; no matter how big or small. For example $\Delta W = F \times \Delta x$. Then it is common to write

$$\lim_{\Delta x \to 0} \frac{\Delta W}{\Delta x} = \frac{\operatorname{d}!W}{\operatorname{d}!x}$$

– Fly by Night Dec 27 '13 at 17:19 -

@FlybyNight Yes I've seen that. I've also seen several calculations where $(\Delta x)^2\approx 0$. shrug – user7530 Dec 27 '13 at 18:49

-

@user7530 I'd be interested to this in context. Do you have a link? – Fly by Night Dec 27 '13 at 19:15

-

The reason for that is, that if $\Delta x$ is "small", then $(\Delta x)^2$ is even smaller – Fakemistake Dec 30 '18 at 10:19

$\Delta x$, is used when you are referring to "large" changes, e.g. the change from 5 to 9. $\partial x$ is used to denote partial derivative when you have a multivariate function (e.g. one with x,y,w, instead of just x alone). $dx$ is used to denote the derivative when you have a univariate function (when you just have x and there is no confusion).

- 527

A 100-words' answer is not required to explain this (as other answers).

See this answer is Quora : What is the difference between dx and Δx?

$ \Delta x$ is a small change(in the context you have used it in) in $x$.

$ dx$ is a vanishingly small change in $x$.

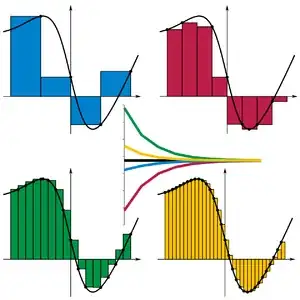

$dx $ is obtained when $ \Delta x$ tends to zero.Look at the width of the rectangles.

Their size gradually decreases as you can see when you move through the four graphs. Only when the rectangle width becomes vanishingly small, the width is called $ dx$.

I think this is the best explanation so far.

- 1,799

- 2

- 26

- 53

Let $y=f(x)$.

$\Delta x$ and $\delta x$ both denote the change in $x$ (or increment of $x$). Some books prefer to use capital delta $\Delta$ and some lowercase delta $\delta$. The change can be small or large, but often we talk about the case that $\Delta x$ is small and especially $\Delta x\to 0$.

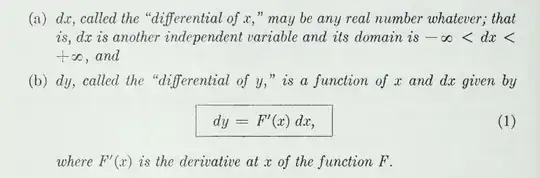

In mathematics, $dx$ is another independent variable which can assume any number. $$-\infty<dx<\infty.$$

$df$ is a function of two variable $x$ and $dx$. Its value is denoted by $dy$ and $$dy=f'(x)dx$$

Therefore,$dx$ does not need to be small. Often in calculus, it is said that $dx=\Delta x$, but there is a difference between them. While $\Delta x$ must be small enough such that $x+\Delta x$ lies within the domain of $f$, there is no restriction on $dx$.

In an old-fashioned approach which is still vastly used in physics, $dx$ is called an infinitesimal (or infinitely small change in $x$). In calculus, use of infinitesimals is sometimes beneficial especially in integration applications (for example to derive the formula of the arc length or areas of surfaces of revolution, etc.) as we do not need to go through limit of sums process.

Unfortunately there are many answers to this question which are completely off-base. And my original answer was deleted, so now I have to add the following reference from Thomas's calculus, 3rd edition.

The notation for partial differentiation is $\partial x$ (and not $\delta x$).

$dx$ is not the limit of $\Delta x$. The limit of $\Delta x$ is zero when $\Delta x\to 0$.

I did not talk about non-standard analysis.

Here is the link for those who want to study more (George B Thomas, Calculus and Analytic Geometry, 3rd edition, p. 82):

- 115

- 7

-

2To say that $\mathbb d x$ "may be any real number whatever" and that $\mathbb d y$ "is a function of $x$ and $\mathbb d x$" is a scandal. That book should be banned and its author fired from where (s)he works. There was a good reason for deleting your previous answer, and I hope that this one has the same fate, since it propagates dangerous nonsense. – Alex M. Jan 17 '23 at 07:18

-

@AlexM. It is a screenshot of Thomas's calculus (one of the most successful calculus books that has ever been written)! Thomas was a professor of mathematics at MIT!! – David R Jan 17 '23 at 08:23

-

2It seems to me that Thomas is trying to say that $dy$ and $dx$ are differential forms. If this is the case then imho one should do it properly and not call them numbers that can take any value. Old fashioned nonsense. – Kurt G. Jan 17 '23 at 09:58

-

@DavidR: In his attempt to make calculus more approachable to beginners, Thomas does more harm than good. So, let me repeat: $\mathbb d x$ is NOT a number! The thing that you call $\Delta x$ in your answer is a number, but $\mathbb d x$ is NOT! Usually, we say that $\mathbb d x$ at a point is a (tangent) covector, and that $\mathbb d x$ as a map depending on the underlying point is a differential $1$-form. In non-standard analysis, $\mathbb d x$ is understood as an infinitesimal (which is a non-standard (!) number). – Alex M. Jan 17 '23 at 10:28

-

@AlexM. I did not write that $dx$ is a number. What I wrote was "dx is an independent variable that can take/assume any number." In calculus textbooks, $dx$ is typically called an independent variable and $dy$ a function of $x$ and $dx$. To call what Thomas (who was one of greatest educators) wrote dangerous and harmful is quite a bold statement! – David R Jan 17 '23 at 10:41

-

@KurtG. The same definition is presented even in the latest edition of Thomas's (and many more including the famous book of Stewart). In the latest edition of Thomas's, they have deleted the part dx can represent any number. But in Stewart's, "dx can be given the value of any real number. – David R Jan 17 '23 at 10:49

-

1What is an "independent variable that can take/assume any number" but is not a number? Sounds like hocus pocus. I am looking at James Stewart, Calculus - Early Transcendentals 6th ed. 2008 where the author writes on p. 250 almost verbally the same as Thomas. These books obviously have a lot of pedagogical value and focus on visual and geometrical explanations. However trying to avoid rigor comes at a price. Stewart mentions non-standard analysis and differential form not once since his target audience are students who get in touch with calculus for the first time. – Kurt G. Jan 17 '23 at 12:17

-

@DavidR: Of course you did write that $\mathbb d x$ is a number! When you wrote in mathematical symbols that $-\infty < \mathbb d x < \infty$ what else do you think that you did? Come on, let us end the discussion here. But just so that you know, probably the most basic definition of $\mathbb d x_i$ is that it is the linear form defined on $\mathbb R^n$ by $\mathbb d x_i (v_1, \dots, v_n) = v_i$. Nothing else. – Alex M. Jan 17 '23 at 16:24

-

@KurtG. The person who asked this question needed a basic answer (something at the level of Calc 1), and the answer that I provided is what students are taught in Calc 1. I don't understand the outrage against this answer while some other answers are completely wrong! If you don't like what Stewart and Thomas teach at Calc 1, what is the right answer at Calc 1 level? – David R Jan 17 '23 at 17:36

-

1

-

Larson writes "The differential of x (denoted by dx) is any nonzero real number." Anton writes "define dx to be an independent variable that can have any real value". Even G.H. Hardy in his influential book Pure Mathematics implies that dx is a number. I don't think that Apostol and Spivak ever tried to define differentials. I'd like KurtG. and @AlexM. go ahead and provide a reasonable definition for differentials at the level of Calc 1 and if they wanted to teach Calc 1 which textbooks they would use. I think AlexM wants to have all of these authors fired (some of them have passed away!). – David R Jan 17 '23 at 18:02

-

@DavidR: The definition that I have given to you above is precisely the one that was given to me in my first year of university studies (in pure mathematics). – Alex M. Jan 17 '23 at 18:05

-

@DavidR All those respectable authors could have gone the extra little step to motivate (if not rigorously introduce) to Calc I students why Elie Cartan came up with differntial forms: We know that for all numbers $\Delta x$ the relation $\Delta f=f'(x),\Delta x$ holds. Now define -as Cartan did- $dx$ to be the linear form that sends a vector $\boldsymbol{v}$ to its first component. In particular, $$ dx(\boldsymbol{v})=v_1,,\text{ or if you like, }\quad dx\begin{pmatrix}\Delta x\\Delta f\end{pmatrix}=\Delta x,. $$ – Kurt G. Jan 21 '23 at 04:39

-

@DavidR . cont. Then $df$ is the linear form that sends $\begin{pmatrix}\Delta x\\Delta f\end{pmatrix}$ to $\Delta f,.$ This allows us to write $$ df(\boldsymbol{v})=f'(x),dx(\boldsymbol{v}) $$ which is an equation of numbers. In contrast, $df=f',dx$ is an equation of forms. Presumably Calc I students have heard in Linear Algebra I what a linear form is. – Kurt G. Jan 21 '23 at 04:39

-

@KurtG. Thanks for your answer. I think there are some typos as $\Delta f$ is not $f'(x)\Delta x$. As a simple defn, we can start with $df(a)(h)=f'(a)h$. Since $dx(a)(h)=h$, we loosely write $df=f'(a)dx$. I'd also say that we attach dx-dy plane to $(a,f(a))$, so the graph of $dy=f'(a)dx$ coincides with the tangent line. By the way, a student of Calc1 asks the instructor why we need such definitions and the answer can't be "you will see why we define it as such in your future courses." These authors define differentials because they need it in the course (for example for integration by parts). – David R Jan 21 '23 at 10:25

-

@DavidR $\Delta f$ is $f'(x),\Delta x$ if we evaluate $f$ in $\Delta f$ at the right two points. The rest what you say in that last comment is fine with me. I am however against hiding modern definitions (eg. of differential forms) from Calc I students as if they were not mature enough to hear about such stuff. I wanted to demonstrate only that this could be done at zero cost. – Kurt G. Jan 21 '23 at 11:00

There are several answers to similar/the same questions:

- Given $z=f(x,y)$, what's the difference between $\frac{dz}{dx}$ and $ \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}$?

- What is the difference between $d$ and $\partial$?

But the answer from Tom Au also puts it in a nutshell.

- 203