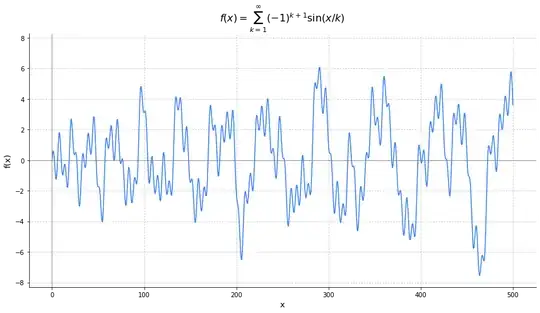

I am investigating the properties of the function $f(x)$ defined for $x \in \mathbb{C}$ by the series: $$f(x) = \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} (-1)^{k+1} \sin\left(\frac{x}{k}\right)$$

This function was the subject of a previous question on its boundedness, where it was shown to be unbounded on $\mathbb{R}$. Also numerically studies about its zeroes where conducted here.

My question is whether we can prove that $f(x)$ has infinitely many real zeros. I have summarized my current understanding of the function's properties below.

Function's properties

Entire Function:

- The function $f(x)$ is entire (analytic on the whole complex plane $\mathbb{C}$).

- Proof Idea: Each term $\sin(x/k)$ is an entire function. By pairing terms like $\sin(x/(2k-1)) - \sin(x/(2k))$ and using sum-to-product identities, the general term of the paired series can be shown to be $O(1/k^2)$ for $x$ in any compact set. Since $\sum 1/k^2$ converges, the series for $f(x)$ converges uniformly on compact subsets of $\mathbb{C}$ by the Weierstrass M-test.

Taylor Series Expansion:

- Around $x=0$, the Taylor series is given by $f(x) = \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^j \eta(2j+1)}{(2j+1)!} x^{2j+1}$, where $\eta(s)$ is the Dirichlet eta function.

- Proof Idea: Substitute the Taylor series for $\sin(w)$. The radius of convergence is $\infty$. Note that $f'(0) = \eta(1) = \ln 2$.

Symmetry:

- $f(x)$ is an odd function: $f(-x) = -f(x)$, which trivially implies $f(0)=0$.

Order of Growth:

- The order of growth $\rho$ of the entire function $f(x)$ is $\rho = 1$.

- Proof Idea: Computed using the formula $\rho = \limsup_{n\to\infty} \frac{n \log n}{-\log |a_n|}$ with the Taylor coefficients $a_{2j+1}$ and Stirling's approximation for $\log((2j+1)!)$.

Hadamard Factorization:

- As an entire function of order $\rho=1$ with a simple zero at $x=0$, $f(x)$ admits the representation: $$f(x) = (\ln 2) x \prod_{j=1}^\infty \left(1 - \frac{x^2}{z_j^2}\right)$$ where $\{\pm z_j\}_{j=1}^\infty$ are the non-zero zeros of $f(x)$ in the complex plane.

- Proof Idea: Apply Hadamard's Factorization Theorem for $\rho=1$. The odd property ensures the product combines to the form $(1-x^2/z_j^2)$. This representation implies $f(x)$ has infinitely many complex zeros $z_j$ such that the series $\sum_{j=1}^\infty |z_j|^{-2}$ converges.

Unboundedness on $\mathbb{R}$:

- The function $f(x)$ is unbounded on the real line $\mathbb{R}$.

- Proof Idea: This was shown in the post. The argument relies on assuming $|f(x)| \le M$ and reaching a contradiction. It uses a limiting orthogonality relation for the functions $\psi_k(x) = \sin(x/k)$ to show that $\limsup_{T\to\infty} \frac{1}{T}\int_0^T f(x)^2 dx$ must be infinite, contradicting the bound $M^2$.

Asymptotic Growth Rate on $\mathbb{R}$:

- It seems that $|f(x)| = O(\sqrt{|x|})$ as $|x| \to \infty$.

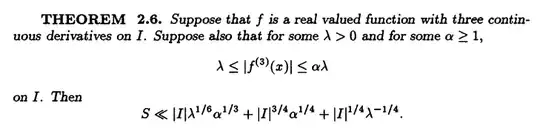

- Proof Idea: Use the absolutely convergent series obtained by pairing terms: $f(x) = \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} [\sin(\frac{x}{2m-1}) - \sin(\frac{x}{2m})]$. This can be rewritten as $f(x) = 2 \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} \cos\left(\frac{x(4m-1)}{4m(2m-1)}\right) \sin\left(\frac{x}{4m(2m-1)}\right)$. Split the sum at $N \approx \sqrt{|x|}$. Bound the initial part of the sum by $O(N) \approx O(\sqrt{|x|})$ and the tail by $O(|x|/N) \approx O(\sqrt{|x|})$.

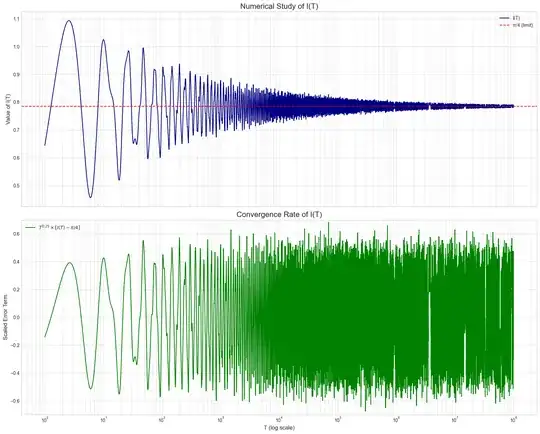

Mean-Square Lower Bound on $\mathbb{R}$:

- There exists a positive constant $c$ such that for all sufficiently large $T$, the function $f(x)$ satisfies the inequality: $\int_0^T f(x)^2 dx \ge \frac{c T^{3/2}}{\sqrt{\ln T}}$.

- Proof Idea: As detailed in this answer, this property provides a strong quantitative version of unboundedness. The proof analyzes the non-negative quantity $\frac{1}{T}\int_0^T (f(x) - S_N(x))^2 dx \ge 0$ for a partial sum $S_N(x)$. This leads to a lower bound for $\int_0^T f(x)^2 dx$ in terms of $N$ and $T$, accompanied by several error terms from finite-$T$ inner products. By carefully bounding these error terms and optimizing the choice of $N$ as a function of $T$ (specifically $N \sim \sqrt{T/\ln T}$), the stated growth rate is established. This result rigorously proves that any growth exponent $\epsilon$ for $f(x)=O(x^\epsilon)$ must satisfy $\epsilon \ge 1/4$.

Divergence of Associated Integrals:

- The improper integrals $\int_1^\infty |f(x)| dx$ and $\int_1^\infty \frac{|f(x)|}{x} dx$ both diverge.

- Proof Idea: This is a key consequence of the conflict between the mean-square lower bound (Property 7) and the asymptotic upper bound (Property 8). As shown in this answer, the proof proceeds by contradiction. Assuming $\int_1^\infty \frac{|f(x)|}{x} dx$ converges, the upper bound $|f(x)| = O(\sqrt{|x|})$ implies that $\int_1^\infty \frac{f(x)^2}{x^{3/2}} dx$ must also converge. However, using integration by parts and the mean-square lower bound from Property 7, it can be shown that this same integral must diverge, which is a contradiction. Note that @Conrad in his answer has proven it with a simpler argument based "only" on the weaker results $\frac{1}{T}\int_0^Tf(x)\sin (x/k) \, dx \to (-1)^{k+1}/2$ impliying $\frac{1}{T}\int_T^{2T}f(x)\sin x \, dx \ge 1/4$ and the result. Nice !

Question

The Hadamard factorization guarantees infinitely many zeros in $\mathbb{C}$, but does not directly tell us if any of these zeros (other than $x=0$) are real. How can one prove that $f(x)$ has infinitely many real zeros ? Intuitively, a continuous, unbounded, and oscillatory function like this should cross the x-axis infinitely often. A natural approach would be to use the Intermediate Value Theorem, which would require finding a sequence of points $x_n \to \infty$ such that the sign of $f(x_n)$ alternates. However, the slow growth and complex behavior make it difficult to prove this.

Using an Integral Transform

A related post, suggested after this question was posted, offered a promising path forward. A proof can be advanced by contradiction using an integral transform. Assume $f(x)$ has a last positive zero $X_0$, so that for all $x > X_0$, $f(x)$ is either strictly positive or strictly negative. We can test these two cases with the integral $J(w) = \int_0^\infty f(t) \frac{e^{-t/w}}{t} dt$ for $w>0$. The integral is well-defined, as the singularity of the kernel at $t=0$ is removed by $f(t)/t \to \ln 2$, and the interchange of summation and integration is justifiable. The crucial property of this transform is that for large $w$, its sign is determined by the behavior of $f(t)$ on $(X_0, \infty)$. This is because the integral over $[0, X_0]$ converges to a finite constant as $w\to\infty$, while, under the hypothesis of a constant sign for $f(t)$ on $(X_0, \infty)$, the known divergence of $\int_{X_0}^\infty |f(t)|/t \, dt$ (Property 9) forces the integral $\int_{X_0}^\infty f(t)/t \, dt$ to also diverge (to either $+\infty$ or $-\infty$). The tail integral therefore dominates the head integral, and its sign dictates the sign of $J(w)$ for large $w$. An explicit calculation, by integrating the series term-by-term, yields $J(w) = \sum_{j=1}^{\infty} (-1)^{j+1} \arctan(w/j)$. By the alternating series test, this sum is strictly positive for all $w>0$. This result directly contradicts the possibility that $f(x)$ is ultimately negative. However, it is consistent with $f(x)$ being ultimately positive. The proof would be complete upon finding a second kernel whose corresponding integral transform can be shown to be negative for arbitrarily large $w$.