Title says it all. I know this is quite odd since one learning the Jordan Normal Form would have already seen a proof of the Spectral Theorem. In my context it makes sense though, I'm doing a uni presentation on a proof that that every matrice is similar to one in Jordan Normal Form and I think proving the Spectral Theorem as a consequence would be a good way to show the power of the theorem. The critical thing I don't know why is true is that the eigenvalues of a normal matrice have algebraic multiplicity equal to geometric multiplicity. Do you know why this is the case or can give me sources that explain it? Thanks in advance

-

1There is no single 'Spectral Theorem' — there are several, depending on context. Which one are you referring to? Please specify it in your question. – Daniel Smania Jun 19 '25 at 13:47

-

You can use the first answer to this question https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/68762/a-is-normal-and-nilpotent-show-a-0 to show that the nilpotent part must be zero. – lcv Jun 19 '25 at 14:12

-

I mean that every normal complex matrice is similar to a diagonal one @DanielSmania. – Arthur Farias Zaneti Jun 21 '25 at 09:40

1 Answers

Claim 1. If $A^*=A$ then $A$ is diagonalizable using an orthogonal basis.

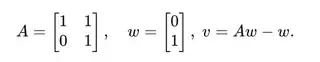

Proof. Let $J$ be the Jordan normal form of $A$. If $J$ consists only of $1\times1$ blocks we are done. Otherwise, there exists a Jordan block of size at least $2$ associated with an eigenvalue $\lambda\in\mathbb{C}$. Equivalently, there is a vector $w$ such that $(A-\lambda I)w\neq0$ but $(A-\lambda I)^2w=0$.

Case 1: $\lambda=0$. Then $Aw\neq0$ while $A^2w=0$. However, $$ \|Aw\|^{2}=\langle Aw,Aw\rangle=\langle w,A^{*}Aw\rangle=\langle w,A^{2}w\rangle=0, $$ a contradiction.

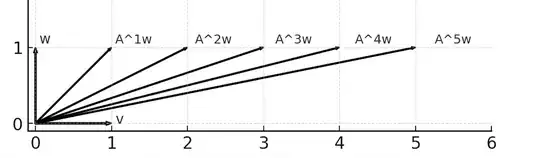

Case 2: $\lambda\neq0$. Set $v=Aw-\lambda w$. Then $v$ is an eigenvector of $A$ with eigenvalue $\lambda$. By induction, $$ A^{n}w=n\lambda^{\,n-1}v+\lambda^{\,n}w. $$ Thus the direction of $A^{n}w$ approaches that of $v$ as $n\to\infty$: the first term dominates the second, so $A^{n}$ increasingly shears the image of $w$ toward $v$ (See the example below with $\lambda=1$).

Because $w$ and $v$ are linearly independent, choose $\alpha,\beta\in\mathbb{C}$ with $\beta\neq0$ such that $u=\alpha v+\beta w$ satisfies $u\perp v$. Since $A=A^{*}$, $$ \langle Au,v\rangle=\langle u,A^{*}v\rangle=\langle u,Av\rangle=\langle u,\lambda v\rangle=0,\tag{*} $$ so $Au\perp v$. Inductively, $$ A^{n}u\perp v\quad\text{for every }n.\tag{**} $$ On the other hand, $$ \langle A^{n}u,v\rangle =\Bigl\langle \lambda^{\,n-1}\bigl(\alpha\lambda+\beta n\bigr)v+\beta\lambda^{\,n}w,\;v\Bigr\rangle =\lambda^{\,n-1}\Bigl((\alpha\lambda+\beta n)\|v\|^{2}+\beta\lambda\langle w,v\rangle\Bigr). $$ For $n$ large the right-hand side is non-zero, contradicting $(**)$.

Therefore no Jordan block of size $\ge2$ can occur, and $A$ is diagonalizable.

Using the argument in $(*)$, we can show that the eigenspaces are pairwise orthogonal, and therefore we can construct an orthogonal basis that diagonalizes the operator $A$.

$\square$

Claim 2. Every normal operator $B$ is diagonalizable.

Proof. Decompose $B$ as $B = H + iK$, where $$ H = \frac{B + B^*}{2}, \qquad K = \frac{B - B^*}{2i}. $$ We have $H^* = H$, $K^* = K$, and $HK = KH$. By Claim 1, a simple argument shows that two commuting self-adjoint operators are diagonalizable in the same orthonormal basis. Consequently, $H$ and $K$ are simultaneously diagonalizable, and hence so is $B = H + iK$. $\square$

- 3,185