Yesterday, while playing around with the GeoGebra application, I discovered a beautiful property of conic sections:

Theorem (Direct Statement)

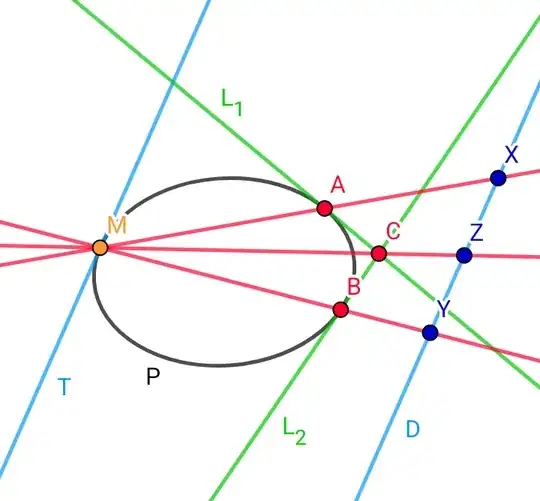

Given: Let $H$ be a plane, and let $P$ be a conic section lying in $H$. Let $D$ be a line in $H$. Let $L_1$ and $L_2$ be tangents to $P$ at points $A$ and $B$, respectively, and suppose they intersect at point $C$. Let $T$ be a line parallel to $D$ and tangent to $P$ at a point $M$. Let $X = AM \cap D$, $Y = BM \cap D$, and $Z = CM \cap D$.

Claim: Point $Z$ is the midpoint of segment $XY$.

Converse Statement

After further reflection, I realized that the converse of this theorem also seems to hold. It can be stated as follows:

Given: Let $H$ be a plane, and let $P$ be a conic section in $H$. Let $D$ be a line in $H$. Let $L_1$ and $L_2$ be tangents to $P$ at points $A$ and $B$, respectively, intersecting at point $C$. Let $T$ be a tangent to $P$ at point $M$ (not necessarily parallel to $D$). Let $X = AM \cap D$, $Y = BM \cap D$, and $Z = CM \cap D$, with the additional condition that $Z$ is the midpoint of segment $XY$.

Claim: Lines $T$ and $D$ are parallel.

My Questions:

Q1: How can we prove the direct theorem stated above?

Q2: Is this theorem known in the literature? If so, could you kindly provide a reference where it is mentioned?

Q3: This theorem implies that there are infinitely many points $M$ in $H$ satisfying the condition (since there are infinitely many conics through $A$ and $B$ with $L_1$ and $L_2$ as tangents). What is the locus of such points $M$ that preserve the midpoint condition for $Z$? Can this locus be constructed from the data of $A$, $B$, $C$, and the line $D$?

Note 1:

You may help me answer this question if you can suggest a method for constructing a conic tangent to two given lines at two known points and passing through a third known point (all in the same plane), using only ruler and compass. (By “constructing a conic with ruler and compass,” I mean: either constructing its key elements such as foci and vertices, or constructing two additional points on the conic — because I already know how to construct a conic through five points using classical tools. See my question and answer on this topic.)

Note 2:

I know how to construct a parabola tangent to two given lines at two given points, using the so-called Steiner generation of a parabola. Therefore, I can construct one point on the locus of $M$. However, I don’t know how to construct any of the other conics tangent to $L_1$ and $L_2$ at $A$ and $B$, respectively. If you can tell me how to construct such a conic, it would be extremely helpful.