I was in class working out the probabilities in the birthday problem (assuming $365$ birthdates). As is commonly known, the probability that there is a birthday match among $n$ people is $$ B(n)=1 - \frac{P(365,n)}{365^n} = 1 - \frac{365!}{(365-n)!365^n}. $$ We generated a quick spreadsheet showing the group size $n$ and the probability of a match, just to gain an appreciation for how quickly the probability $B(n)$ approaches $1$.

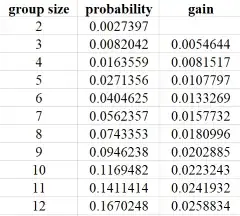

To get insight into how the probability grows when you tack on one extra person, there was the suggestion to add a third column, which was the probability "gain" for lack of a better term: in the row for $n$ people we compute $$ B(n)-B(n-1). $$ So, a snapshot of the sheet looks like

Thus, for example, in going from $11$ to $12$ people we add about $2.59\%$ to the probability of match with $11$ people.

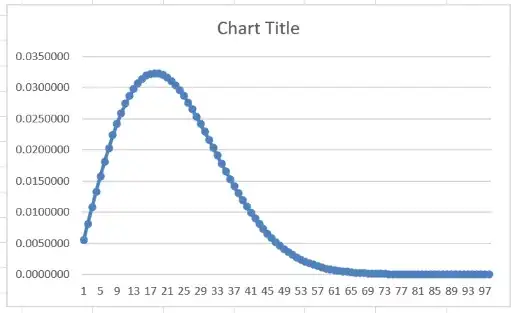

For fun, we worked this out for $1 \leq n \leq 100$ and there is interestingly (to me) a peak in the gain at $n=20$. This surprised me, thought I'm not sure why. I assumed the gain would decrease as the probability $B(n)$ gets closer to $1$, as there's less "headroom" to add much probability. This is true, but I incorrectly assumed some sort of monotonicity throughout.

What is the mathematical explanation for both the peak gain and its location? (Obviously this changes as you change the number of birthdates.) I've tried working out the difference $B(n)-B(n-1)$ but it's not insightful (to me). I can't do Calculus on this, as it's not continuous. Is this approximately some easily-seen continuous function, and that shows the maximum in a nice, intuitive way? How can we reason that a peak should occur at all?