I figure some historical context may be of interest. The computation in the question is a particular instance of Borchardt's algorithm. This algorithm can be considered as a generalization of Archimedes' algorithm for the approximation of $\pi$ via inscribed and circumscribed regular polygons. I have pointed to the primary sources for this algorithm by Pfaff, Gauss, Schwab [1], and Borchardt in a previous answer on this site. The algorithm is defined by two linked sequences:

$$a_{i+1} = \frac{1}{2} \left(a_{i}+b_{i}\right)$$

$$b_{i+1} = \sqrt{a_{i+1}b_{i}}$$

If for $m \gt n$, one sets $a_{0}=m$ and $b_{0}=n$, then for $i \to \infty$, the $a_{i}$ and $b_{i}$ converge to a common limit

$$\omega =\frac{\sqrt{m^{2}-n^{2}}}{\cosh^{-1}\left(\frac{m}{n} \right)} $$

If, for $x > 1$, one sets $m=\frac{1}{2}(x+1)$ and $n=\sqrt{x}$, then $\omega = \frac{x-1}{\log(x)}$, which is precisely the function from the question.

For $m < n$ the common limit is instead

$$\omega =\frac{\sqrt{n^{2}-m^{2}}}{\cos^{-1}\left(\frac{m}{n} \right)} $$

illustrating the extension from the trigonometric space to the hyperbolic space provided by the algorithm. Borchardt's algorithm converges slowly, reducing the error relative to $\omega$ by only a factor of four per iteration. In both trigonometric and hyperbolic variants, the interpolation $\frac{1}{3}a_{n}+\frac{2}{3}b_{n}$ provides useful convergence acceleration: for any particular chosen error limit the variant using interpolation requires only half the number of iterations needed without the use of interpolation.

For the earlier algorithm of Archimedes and it sequences of inscribed and circumscribed polygons awareness of this interpolation goes back at least to Huygens' 1654 publication De circuli magnitudine inventa. In his theorem IX he states that (tr. Hazel Pearson, M.A. thesis, Boston University 1922) "the circumference of a circle is less than two-thirds the perimeter of the equilateral inscribed polygon plus one third the perimeter of a similar circumscribed polygon."

[1] As Schwab's independent work is not as often credited as that of his better-known mathematical colleagues, I will give a brief outline here. Given a regular $n$-gon with perimeter $P$, and each side $S = P / n$, the radius of the inscribed circle is

$$ a = r_{inscribed} = P / (2 n \tan (\pi / n)) = S / (2 \tan (\pi / n)) $$

while the radius of the circumscribed circle is

$$ b = r_{circumscribed} = P / (2 n \sin (\pi / n)) = S / (2 \sin (\pi / n))$$

Jacques Schwab, "Élémens de géométrie". Nancy: C.-J. Hissette 1813, p. 104, presented the following result based on a geometric proof:

Let $a$ and $b$ be the radii of the inscribed and circumscribed circles of a regular $n$-gon with perimeter $P$. Then the corresponding quantities $a'$ and $b'$ of a regular $2n$-gon with the same perimeter $P$ are:

$$ a' = (a + b) / 2 $$

$$ b' = \sqrt{a' * b} $$

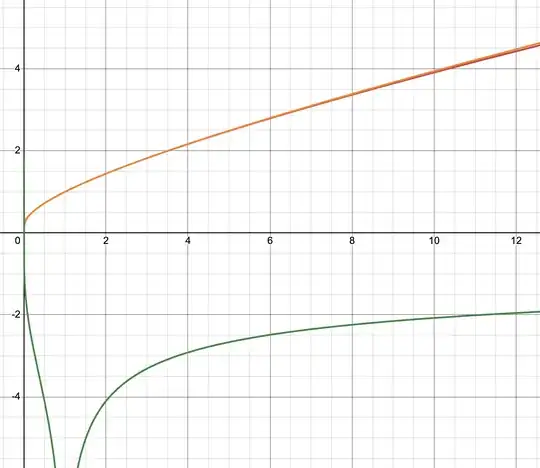

I notice your approximant is a convex linear combination of those other two means. This motivates, to me, to investigate the function $$ \newcommand{\l}{\lambda} r(x,\l) := \frac{f(x)-a(x,\l)}{f(x)} $$ where $f$ is the original function $$ f(x) := \frac{x-1}{\ln x} $$ and $a$ is the approximant, as a general convex combination, $$ a(x,\l) := \l \sqrt x + (1-\l) \frac{x+1}{2} $$ (Here, $\l \in [0,1]$. $r$ is the relative error.)

– PrincessEev Mar 27 '25 at 06:16