This is a partial follow-up to this question.

Suppose we start off with a (finite) set of points $S_0\subset \mathbb{R}^2$. Repeat the iteration $$S_{k+1}=\left\{\frac{p+q}{2}\mid p,q\in S_k\wedge p\not=q\right\}$$ which is getting the set of midpoints between all pairs of points. It looks like there is always an open set $T\subset \mathbb{R}^2$ that $S_k$ 'approaches'. By this, I mean that it looks like for all $\epsilon>0$, there is some $K$ such that for all $k\ge K$, $0<\max_{p\in S_k}d(p,T)<\epsilon$.

If $|S_0|\le 2$, then $T$ is the empty set. If $|S_0|=3$, it would converge to a point, which also corresponds to the empty set (since we have the stipulation that $T$ is open). But it already gets complicated when $|S_0|=4$, even when it's a square (arguably the simplest example with $4$ points). Moreover, if we say $S_0$ is any arbitrary (finite) set of points in $\mathbb{R}^2$, the number of elements in $S_k$ blows up super-exponentially. With $|S_0|=4$, the number of elements in $S_k$ is about $2\cdot c^{2^n}$, where $c\approx 1.28$. However, if we restrict $S_0$ to only be points lying on some lattice, the number of points "only" increases exponentially.

I think the case of a square is the smallest interesting example - what is $T$ if we start off with a square?

Let's say $S_{-2}=\{(-2,-2),(-2,2),(2,-2),(2,2)\}$, the square with side lengths $4$, so that $S_0=\{-1,0,1\}^2$. I had a side length of $4$ at the beginning because the radius of the smallest circle containing $S_k$ approaches $1$.

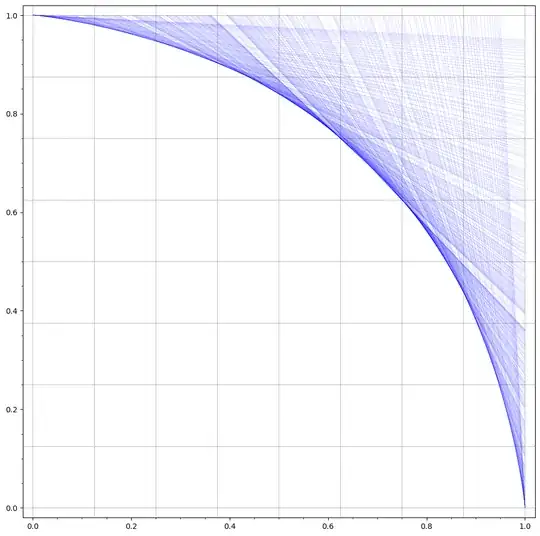

Define the safe points $S_k'\subseteq S_k$ to be those that will always remain in future iterations. These are precisely the points $p\in S_k$ such that there exist two different $x,y\in S_k$ such that $x+y=2p$. Let $A_k$ be the convex hull of $S_k'$, and $B_k$ be the convex hull of $S_k$. Then $A_k\subseteq S_{k+1},T\subseteq B_k$, so we can keep refining what $T$ is. It also looks like $B_k\setminus A_k$ has area approaching $0$ (which implies that we can define $T$ as the 'limit' of $A_k$ or of $B_k$).

Numerically, it looks like the slope of the boundary of both $A_k$ and $B_k$ is $-1$ from $5/8$ to $3/4$. It's possible that we can figure out the slope of the boundary for an arbitrary $x\in(0,1)$, and then use that to identify the boundary of $T$, but I'm not sure how to analytically find the slope or even if it's well-defined. It probably isn't well-defined for much of the set $\left\{\frac{a}{2^b}\mid a,b\in\mathbb{Z}\right\}$, since the convex hulls could have cusps at those points.

Based on $S_{18}$, the area of $A_{18}$ is $\frac{51901287739}{4^{17}}=3.0210525\dots$, while the area of $B_{18}$ is $\frac{51901289787}{4^{17}}=3.0210526\dots$. This implies that the area of $T$ (assuming the area of $B_k\setminus A_k$ goes to $0$) is $3.021052\dots$.

My questions are about the area of $T$ and the shape of the boundary of $T$. How can we find either/both of these?

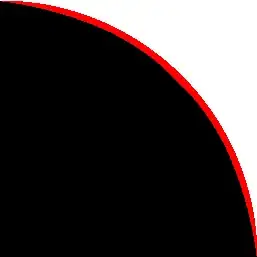

This picture shows what the top-right part of $S_8$ looks like. The black indicates the actual points in $S_8$, while the red is the part of the radius-$1$ circle that is not in $S_8$.