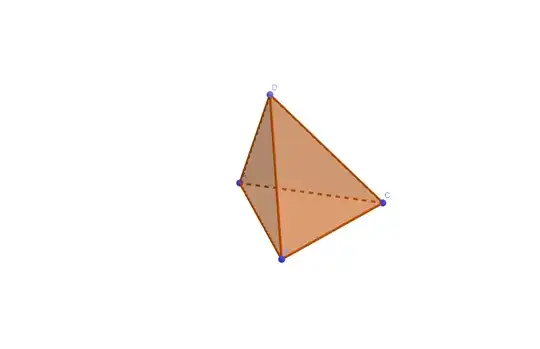

I'll switch to notation most familiar to me and consider tetrahedron $OABC$ with edge-lengths

$$a:=|OA|\quad b:=|OB|\quad c:=|OC| \quad d:=|BC| \quad e:=|CA|\quad f:=|AB|$$ with dihedral angles $A:=\angle OA$, $B:=\angle OB$, $C:=\angle OC$, $D:=\angle AB$, $E:=\angle BC$, $F:=\angle CA$ along respective edges. (There should be no confusion in re-purpose $A$, $B$, $C$ here.) Also, face-areas

$$W:=|\triangle ABC| \quad X:=|\triangle OBC|\quad Y:=|\triangle OCA|\quad Z:=|\triangle OAB|$$

Finally, the insphere meets faces $W$, $X$, $Y$, $Z$ at $O'$, $A'$, $B'$, $C'$.

With a bit of Mathematica-assisted coordinate bashing, I find

$$\begin{align}

S_{OA} =|\triangle OAC'|=|\triangle OAC'| &= \frac{YZ(1 + \cos A)}{W + X + Y + Z} \\[4pt]

S_{BC} =|\triangle BCO'|=|\triangle BCA'| &= \frac{WX(1 + \cos D)}{W + X + Y + Z} \\[8pt]

S_{OB} =|\triangle OBA'|=|\triangle OBA'| &= \frac{ZX(1 + \cos B)}{W + X + Y + Z} \\[4pt]

S_{CA} =|\triangle CAO'|=|\triangle CAB'| &= \frac{WY(1 + \cos E)}{W + X + Y + Z} \\[8pt]

S_{OC} =|\triangle OCB'|=|\triangle OCB'| &= \frac{XY(1 + \cos C)}{W + X + Y + Z} \\[4pt]

S_{AB} =|\triangle ABO'|=|\triangle ABC'| &= \frac{WZ(1 + \cos F)}{W + X + Y + Z}

\end{align} \tag1$$

(Note: The faces in the numerator bound the dihedral angle. Also, we could write $1+\cos\theta=2\cos^2\frac12\theta$; this may-or-may-not make the fractions neater to the reader, but it won't help with the ultimate task.)

The side-lengths of the ostensible triangle are in the proportion

$$\begin{align}

&S_{OA}S_{BC}:S_{OB}S_{CA}:S_{OC}S_{AB} \\[4pt]

=\;&\underbrace{(1+\cos A)(1+\cos D)}_p:

\underbrace{(1+\cos B)(1+\cos E)}_q:

\underbrace{(1+\cos C)(1+\cos F)}_r \tag2

\end{align}$$

(ignoring a common scale factor of $\dfrac{WXYZ}{(W+X+Y+Z)^2}$).

So, the question becomes:

Do $p$, $q$, $r$ always form a triangle?

The answer is

No.

Take, for instance, consider these edge-lengths and face-angles about vertex $O$:

$$a=b=c=1 \qquad

\alpha := \angle BOC = 90^\circ \qquad

\beta := \angle COA = 72^\circ \qquad

\gamma := \angle AOB = 36^\circ \tag3$$

These give us face areas:

$$X=\frac12b c \sin\alpha = \frac12 \qquad Y = \frac14\sqrt{\frac12(5+\sqrt5)} \qquad

Z = \frac14\sqrt{\frac12(5-\sqrt{5})} \tag4$$

$$W=\sqrt{X^2+Y^2+Z^2-2YZ\cos A-2ZX\cos B-2XY\cos C} = \frac14 \sqrt{11 - 4 \sqrt5}$$

Also, using a Spherical Law of Cosines, they give us $\cos A$, $\cos B$, $\cos C$:

$$\cos A = \frac{\cos\alpha-\cos\beta\cos\gamma}{\sin\beta\sin\gamma} = -\frac{1}{\sqrt5} \quad

\cos B = \frac{\sqrt5 - 1}{\sqrt{2 (5 - \sqrt5)}} \quad

\cos C = \frac{\sqrt5 + 1}{\sqrt{2 (5 + \sqrt5)}} \tag5

$$

Finally, a(nother) tetrahedral Law of Cosines gives us $D$, $E$, $F$

$$\begin{align}

Y^2+Z^2-2Y Z \cos A &= W^2 + X^2 - 2 W X \cos D &&\to\quad

\cos D = \frac{2 - \sqrt5}{\sqrt{11 - 4 \sqrt5}} \\[6pt]

Z^2+X^2-2ZX \cos B &= W^2 + Y^2 - 2 W Y \cos E &&\to\quad

\cos E = \frac{5 - \sqrt5}{\sqrt{70 - 18 \sqrt5}} \\[6pt]

X^2+Y^2-2XY \cos C &= W^2 + Z^2 - 2 W Z \cos F &&\to\quad

\cos F = \frac{9 - 3 \sqrt5}{\sqrt{150 - 62\sqrt5}}

\end{align}\tag6$$

From these, we obtain

$$p = 0.4617\ldots \qquad

q = 2.2988\ldots \qquad

r = 3.1088\ldots \tag7$$

Since $p+q<r$, these values fail the Triangle Inequality, so they do not form a triangle. $\square$

Addendum. While symbol-crunching, I found the following:

$$\begin{align}

\frac{W(-p+q+r)}{\sin B\sin C} &\;=\; (W-X+Y+Z)\cot B_2\cot C_2 \;-\;(W+X+Y+Z)\cos\alpha \\[4pt]

\frac{W(\phantom{-}p-q+r)}{\sin C\sin A} &\;=\; (W+X-Y+Z)\cot C_2\cot A_2 \;-\;(W+X+Y+Z)\cos\beta \\[4pt]

\frac{W(\phantom{-}p+q-r)}{\sin A\sin B} &\;=\; (W+X+Y-Z)\cot A_2\cot B_2 \;-\;(W+X+Y+Z)\cos\gamma

\end{align} \tag{A.1}$$

where $\theta_2:=\frac12\theta$ is a favorite bit of notational shorthand.

We then have that $p$, $q$, $r$ form a triangle when (and only when) the right-hand expressions are non-negative. Having these expressions in terms of elements surrounding vertex $O$ (with $W$ computable from such elements) may aid future investigations, as it can be common to parameterize a tetrahedron (as I did above) using $a$, $b$, $c$, $\alpha$, $\beta$, $\gamma$.

Addendum 2. In a comment, OP effectively asks

Do $\sqrt{p}$, $\sqrt{q}$, $\sqrt{r}$ always form a triangle?

That answer is

Yes!

The quickest way to verify this is to note that Heron's formula for the (square of the) area $T$ of a triangle with sides $u$, $v$, $w$ ...

$$16 T^2 = (u+v+w)(-u+v+w)(u-v+w)(u+v-w) \tag{B.1} $$

... actually serves as a simultaneous checker of all three aspects of the Triangle Inequality for candidate (positive) sides $u$, $v$, $w$:

If (and only if) the right-hand side of (B.1) evaluates to a non-negative number, then (and only then) $u$, $v$, $w$ are sides of a valid triangle.

(Replace "non-negative" with "positive" for non-degenerate cases. Here, we'll allow them.)

The necessarily-positive $(u+v+w)$ factor in (B.1) is clearly irrelevant to the valid-triangle determination as it doesn't affect the sign, but notice the result of expanding the four-factor expression:

$$16T^2 = -u^4-v^4-w^4+2v^2w^2+2w^2u^2+2u^2v^2 \tag{B.2}$$

All those even exponents are nicely-suited to circumstances like ours, since they'll eliminate the pesky square roots in $u=\sqrt{p}$, $v=\sqrt{q}$, $w=\sqrt{r}$. So, "all we have to do" is check whether this expression is non-negative:

$$-p^2-q^2-r^2+2qr+2rp+2pq \tag{B.3}$$

substituting-in the cosine expressions from $(2)$. My approach is to use what I'll call the "pseudoface enhancement" of the Tetrahedral Law of Cosines (as in this answer to OP's earlier question), assigning $H^2$, $J^2$, $K^2$ (squares of the tetrahedron's "pseudoface" areas) to the three aspects of $(6)$ above. This allows me to write

$$\begin{align}

\cos A = \frac{-H^2+Y^2+Z^2}{2YZ} &\qquad \cos D = \frac{-H^2+W^2+X^2}{2WX} \\[4pt]

\cos B = \frac{-J^2+Z^2+X^2}{2ZX} &\qquad \cos E = \frac{-J^2+W^2+Y^2}{2WY} \\[4pt]

\cos C = \frac{-K^2+X^2+Y^2}{2XY} &\qquad \cos F = \frac{-K^2+W^2+Z^2}{2WZ} \\[4pt]

W^2+X^2+Y^2+Z^2 &= H^2+J^2+K^2

\end{align} \tag{B.4}$$

Making the cosine substitutions and moving things around a bit, I find that (B.3) takes the form

$$\frac{(W + X + Y + Z)^2}{4 W^2 X^2 Y^2 Z^2}\;\left(

\begin{array}{c}

H^2 J^2 K^2 - 2 (W X - Y Z) (W Y - Z X) (W Z - X Y) \\

- H^2 (W X - Y Z)^2 - J^2 (W Y - Z X)^2 - K^2 (W Z - X Y)^2

\end{array}\right) \tag{B.5}$$

with that scary factor being nothing more than $81V^4$, where $V$ is the volume of the tetrahedron. Clearly, then, this expression is non-negative, guaranteeing that $\sqrt{p}$, $\sqrt{q}$, $\sqrt{r}$ do indeed always form a triangle! $\square$

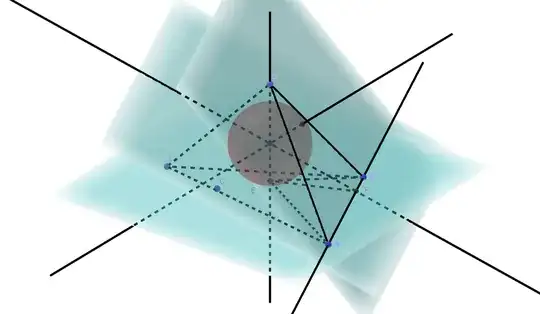

Addendum 3. As requested by OP, here's some background to the coordinate-bashing that led to relations $(1)$.

I typically coordinatize a tetrahedron $OABC$ as

$$O=(0,0,0)\quad A=(a,0,0)\quad B=(b\cos\gamma,b\sin\gamma,0) \tag{C.1}$$

$$C = (c\cos\beta,c\sin\beta\cos A,c\sin\beta\sin A)$$

I calculated the incenter, $I$, via its barycentric coordinates (which I think of simply as the weights in a weighted average of Cartesian coordinates):

$$I = \frac{W O + X A+Y B+Z C}{W+X+Y+Z} \tag{C.2}$$

The Cartesian coordinates of the projection, $C'$ of $I$ onto face $OAB$ (aka, the $xy$-plane) are then simply $C'=(I_x,I_y,0)$. Other projections are messy, but it helps to express $C'$ in weighted-average form relative to $OAB$:

$$\begin{align}

C'&=\frac{uO+vA+wC}{u+v+w} \\[4pt]

u=W(1+\cos F) \quad v&=X(1+\cos B) \quad w=Y(1+\cos A) \\[4pt]

u+v+w &= W+X+Y+Z

\end{align} \tag{C.3}$$

Observe how $u$ associates vertex $O$ of $OAB$ (aka, face $Z$) with face $W$ (with is opposite $O$) and dihedral angle $F$ (which is bounded by faces $W$ and $Z$; likewise, for $v$ and $w$. (That $u+v+w=W+X+Y+Z$ follows from the fact that $Z=W\cos F+X\cos B+Y\cos A$. (Why?)) Consequently, it's "obvious" that we can write rather compactly:

$$\begin{align}

A' &= \frac{uO+vB+wC}{W+X+Y+Z} \\[4pt]

u=W(1+\cos D)\quad v&=Y(1+\cos C) \quad w = Z(1+\cos B) \\[8pt]

B' &= \frac{uO+vC+wA}{W+X+Y+Z} \\[4pt]

u=W(1+\cos E)\quad v&=Z(1+\cos A) \quad w = X(1+\cos C) \\[8pt]

O' &= \frac{uA+vB+wC}{W+X+Y+Z} \\[4pt]

u=X(1+\cos D)\quad v&=Y(1+\cos E) \quad w = Z(1+\cos F) \\[8pt]

\end{align}\tag{C.4}$$

From there, it's straightforward (especially with a tool like Mathematica), to use vector methods to calculate, the various area formulas in $(1)$. For instance,

$$\begin{align}

S_{OA}^2 :=|\triangle OAB'|^2 &=\frac14\left|\overrightarrow{B'O}\times\overrightarrow{B'A}\right|^2 \\[4pt]

&= \frac{ Z^2 a^2 c^2 \sin^2\beta (1 + \cos A)^2}{4 (W+X+Y+Z)^2} \\[4pt]

&= \frac{ Y^2Z^2 (1 + \cos A)^2}{(W+X+Y+Z)^2} \\[4pt]

\end{align} \tag{C.5}$$

Throughout these and other calculations, I'm aided by many(!!!) years of experience interpreting tetrahedral expressions in general, and sussing-out convenient "hedronometric" forms (favoring face-areas and dihedral angles) in particular.

My familiarity with these forms leads me to readily recognize that, for instance, the "scary factor" in (B.5) is proportional to $V^4$. (Indeed, this is Theorem 5 of my note "Heron-like Hedronometric Results for Tetrahedral Volume" (PDF link via daylateanddollarshort.com).) But the sufficiently-motivated reader can verify the equality directly by converting the various areas into expressions using side-lengths (see this old answer for how to convert $H^2$, $J^2$, $K^2$), and comparing it to the result of the Cayley-Menger determinant.

\cdotin MathJax; eg,$SAB \cdot SCD$appears as $SAB \cdot SCD$. – Blue Feb 23 '25 at 07:28