I'm curious about representations of certain abelian groups in $\Bbb{R}^n$, whether they are lattice or dense.

In particular, I was interested in the following group on four generators: $$G := \{ r, b, g, p: r+b+g+p = 0 \}$$

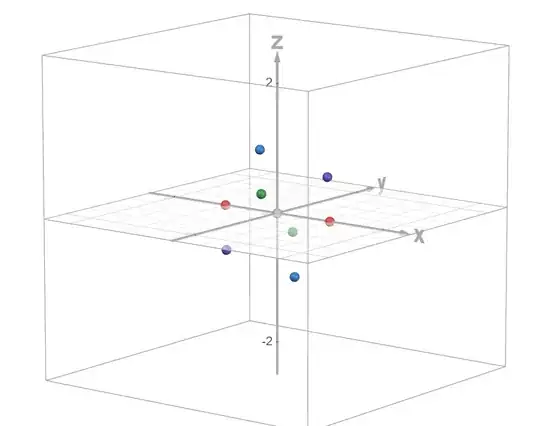

I selected the following four vectors (color coded $r$ = red, $b$ = blue, $g$ = green, $p$ = purple) to represent this group in $\Bbb{R}^3$. For symmetry's sake, I let them be the four vertices of a regular tetrahedron:

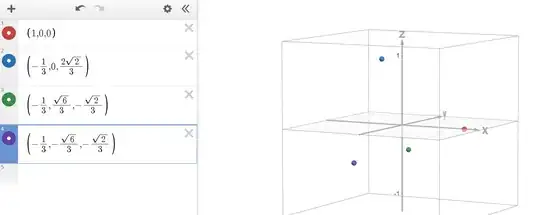

Letting $\vec{x}$ represent the vector representation of generator $x$, we have

\begin{align*}

\vec{r} &= ⟨1, 0, 0⟩ \\

\vec{b} &= ⟨-1/3, 0, 2\sqrt{2}/3⟩ \\

\vec{g} &= ⟨-1/3, \sqrt{6}/3, -\sqrt{2}/3⟩ \\

\vec{p} &= ⟨-1/3, -\sqrt{6}/3, -\sqrt{2}/3⟩ \

\end{align*}

Letting $\vec{x}$ represent the vector representation of generator $x$, we have

\begin{align*}

\vec{r} &= ⟨1, 0, 0⟩ \\

\vec{b} &= ⟨-1/3, 0, 2\sqrt{2}/3⟩ \\

\vec{g} &= ⟨-1/3, \sqrt{6}/3, -\sqrt{2}/3⟩ \\

\vec{p} &= ⟨-1/3, -\sqrt{6}/3, -\sqrt{2}/3⟩ \

\end{align*}

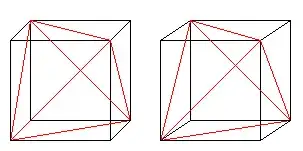

Originally I thought the span of these four vectors under addition would be dense in $\Bbb{R}^3$, but after some cogitation, I now believe the span would be a body-centered cubic lattice, just with a weird orientation in space.

Can anyone either confirm or deny that this is the case?

Also, how would I rotate the "canonical" BCC lattice (with vertices at the integer points and half-integer points of $\Bbb{R}^3$) to get the version that we have here? In addition to stretching everything by $2\sqrt{3}/3$, I mean.

Edit: I added the negatives of each of the four vectors above (negative has the same color as the original), together with the origin (gray), to visually clarify the potential BCC nature of the lattice.