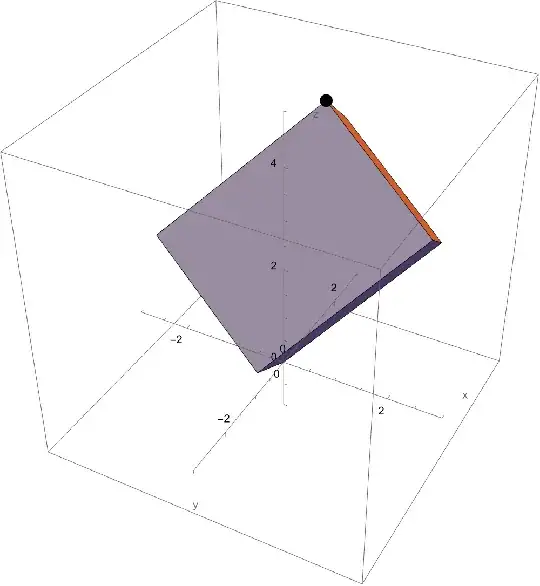

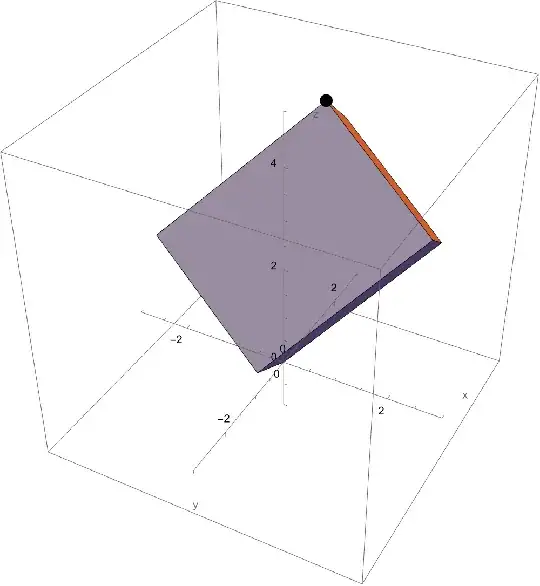

In the special case that $a$ and $b$ are equal, you can, in fact, do it with a rectangular cuboid as long as we choose the side lengths carefully. Note that any rectangular cuboid can have up to three distinct side lengths. For our purposes, let's denote those lengths $a$, $b$, and $c$ in descending order. We simply need the lengths to satisfy

$$a/2^{1/3} = b, \, b/2^{1/3} = c, \text{ and } 2\,a/2^{1/3} = c.$$

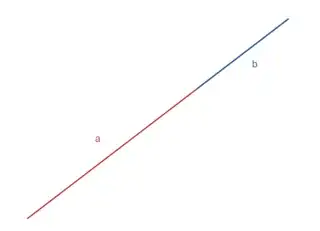

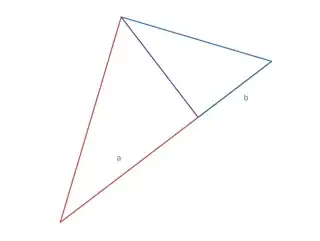

We then define two similarity transformations $f_1$ and $f_2$ that should fix opposite vertices and scale by the factor $2^{1/3}$. Each must also rotate through the angle $120^{\circ}$. To specify the fixed line of the rotation, let $\vec{u}$, $\vec{v}$, and $\vec{w}$ be the unit vectors from the vertex to the three adjacent vertices. The rotation should be about the line through the vertex in the direction of $\vec{u}+\vec{v}+\vec{w}$.

As a result, the side of length of $a$ maps to the side of length $b$ and the side of length $b$ maps to the side of length $c$. The side of length $a$ is replaced by two copies of the side of length $c$.

This situation is illustrated in the animation below where the fixed points are $(0,0,0)$ for one transformation and $(2,2,2)$ for the other.

I guess this could probably be generalized for your other question.

I would guess that you would also be interested in Combinatorial topology of three-dimensional self-affine tiles by Christoph Bandt which describes quite completely the types of self-similar sets whose translates can be used to cover all of three-dimensional space.

The construction above, in fact, can be obtained from his theorem 2.3. That theorem implies that the only way to generate a self-similar set consisting of two copies of itself in 3D that tiles space by translates is to start with

$$

\tilde{M} = \begin{pmatrix}

0 & 0 & \pm 2 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0

\end{pmatrix},

$$

then conjugate that to a similarity matrix $M$, and finally form the IFS with similarities

$$\begin{aligned}

f_1(x,y,z) &= M^{-1}\begin{pmatrix}x \\ y \\ z\end{pmatrix} \\

f_2(x,y,z) &= M^{-1}\begin{pmatrix}x \\ y \\ z\end{pmatrix} + \vec{v},

\end{aligned}$$

where $\vec{v}$ is a non-zero shift vector.

To form the example above, I conjugated $\tilde{M}$ to

$$

M = 2^{1/3}\left(

\begin{array}{ccc}

-\frac{1}{2} & -\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} & 0 \\

\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} & -\frac{1}{2} & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 1 \\

\end{array}

\right)

$$

and chose my shift vector to be

$$

\vec{v} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 1\end{pmatrix}.

$$