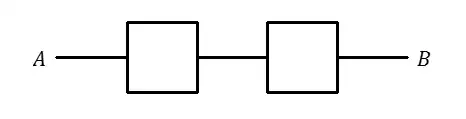

In the diagram, a robot starts at $A$ and moves right. Every time it reaches a fork (i.e. a point where it needs to choose among more than one direction), it chooses its next direction randomly, but does not turn back. It stops when it reaches either $A$ or $B$.

Let $P(B)=$ probability that the robot reaches $B$.

I have worked out that $P(B)=\frac12$, but my proof relies on calculation and is not intuitive.

Is there an intuitive explanation why $P(B)=\frac12$?

Proof that $P(B)=\frac12$

Let $M$ be the midpoint of the diagram. The probability that the robot reaches $M$ is:

$$\frac12+\left(\frac14\right)\left(\frac12\right)+\left(\frac14\right)^2\left(\frac12\right)+\left(\frac14\right)^3\left(\frac12\right)+\cdots=\frac{\frac12}{1-\frac14}=\frac23$$

(Explanation: The probability that it reaches $M$ as quickly as possible is $\frac12$. The probability that it walks $1.5$ loops around the left square then reaches $M$, is $\left(\frac14\right)\left(\frac12\right)$. The probability that it walks $2.5$ loops around the left square then reaches $M$, is $\left(\frac14\right)^2\left(\frac12\right)$. And so on, forming an infinite geometric series.)

If the robot reaches $M$, then the probability that it goes directly (shortest path) to $B$ is $\frac12$, and the probability that it does not go directly to $B$ is $\frac12$. If it does not go directly to $B$, then the probability that it eventually reaches $B$ is $1-P(B)$, by symmetry with the original question. So:

$$P(B)=\frac23\left(\frac12+\frac12\left(1-P(B)\right)\right)$$

$$\therefore P(B)=\frac12$$

(Generalization: If the diagram has $n$ squares, then the probability of reaching $B$ is $\frac{2}{2+n}$. This can be proved by induction.)

Context

A colleague of mine made up this question. I found it interesting because the answer is $\frac12$ and I can't seem to find an intuitive explanation. I am interested in such questions.