I came up with the following question.

Four uniformly random points on a circle are chosen, and line segments are drawn between each pair of points. What is the probability that the longest line segment is between neighboring points?

Exerimental data using Excel suggest that the answer is $\frac23$, and I'm trying to figure out why. I believe the solution may involve order statistics. Or, given that the presumable answer is so simple, maybe there is an elegant argument from symmetry.

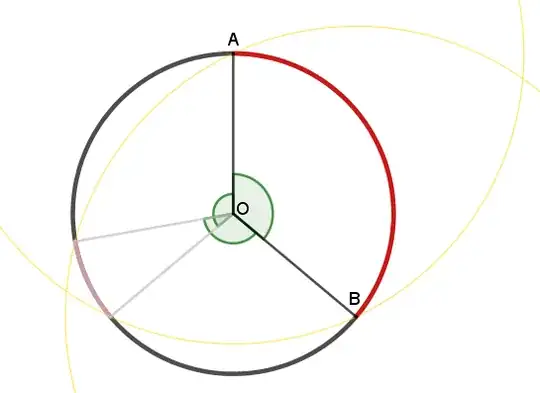

I made a Desmos simulator where you can choose four random points on a circle, and the line segments are shown.

My student's wrong method gives the right answer?

I asked my student this question (without mentioning the experimental data), and she said, "There are six line segments, of which four are between neighboring points, so the probability that the longest line segment is between neighboring points is $\frac46=\frac23$."

Huh? Surely that method is wrong: line segments between opposite points should have larger expected length than line segments between neighboring points, so the six line segments should not be treated the same, right?

Weird.