I finally found a single integral solving the natural generalisation of the problem discussed here:

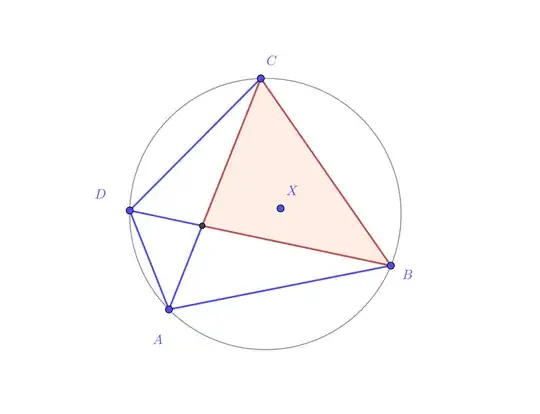

For $n\ge1$ pick $n+2$ points uniformly at random on the unit circle. What is the probability $P_n(x)$ of the convex hull of the points containing $X=(x,0)$ where $0\le x\le1$?

If the convex hull does not contain $X$ exactly one of the following cases must hold:

- All $n+2$ points are on the same side of the $x$-axis ($OX$). This happens with probability $2^{-(n+1)}$.

- There is a point $V$ with Weierstrass parameter $v>0$ and another point $T$ with parameter $t<k/v$ where $k=\frac{x-1}{x+1}$, and none of the remaining points' parameters are between $t$ and $v$. All points thus lie "left" of the segment $TV$ which lies "left" of $X$. The probability of a point falling in the arc $TV$ is $\frac{\arctan v-\arctan t}\pi$, while $t,v$ are Cauchy-distributed and can be selected from the pool of points in $(n+2)(n+1)$ ways. This case's contribution to the overall probability is thus $$\frac{(n+2)(n+1)}{\pi^2}\int_0^\infty\int_{-\infty}^{k/v}\frac1{1+v^2}\frac1{1+t^2}\left(1-\frac{\arctan v-\arctan t}\pi\right)^n\,dt\,dv$$

- There is a point $V$ with Weierstrass parameter $v>0$ and another point $T$ with parameter $k/v<t<0$ and all of the remaining points' parameters are between $t$ and $v$, i.e. they are "right" of $TV$ which in turn is "right" of $X$. By similar reasoning to the previous case the present case's contribution is $$\frac{(n+2)(n+1)}{\pi^2}\int_0^\infty\int_{k/v}^0\frac1{1+v^2}\frac1{1+t^2}\left(\frac{\arctan v-\arctan t}\pi\right)^n\,dt\,dv$$

Putting everything together we have $$P_n(x)=1-2^{-(n+1)}-\frac{(n+2)(n+1)}{\pi^2}\left(\int_0^\infty\int_{-\infty}^{k/v}\frac1{1+v^2}\frac1{1+t^2}\left(1-\frac{\arctan v-\arctan t}\pi\right)^n\,dt\,dv + \int_0^\infty\int_{k/v}^0\frac1{1+v^2}\frac1{1+t^2}\left(\frac{\arctan v-\arctan t}\pi\right)^n\,dt\,dv\right)$$ This can be turned into a single integral by expanding and solving the $t$ integral. Define the polynomial $$Q(V,K)=\sum_{i=0}^n\sum_{j=0}^i\binom ni\binom ij\frac{(-V)^{i-j}}{\pi^i}\frac{K^{j+1}-(-\pi/2)^{j+1}}{j+1}+\sum_{i=0}^n\binom ni\frac{V^{n-i}}{\pi^n}\frac{(-K)^{i+1}}{i+1}$$ Then $$P_n(x)=1-2^{-(n+1)}-\frac{(n+2)(n+1)}{\pi^2}\int_0^\infty\frac{Q(\arctan v,\arctan k/v)}{1+v^2}\,dv$$

I already worked out that $$P_1(x)=\frac14-\frac3{2\pi^2}\operatorname{Li}_2(x^2)$$ The new surprising thing, though, is that numerical calculations strongly suggest $$\boxed{P_2(x)=2P_1(x)}$$ i.e. it is exactly twice as likely that four random points on the unit circle will enclose $X$ than will three random points, no matter where $X$ is. This relation does not extend to $P_3(x)$ and beyond.

How can the boxed relation be proved?