About a month ago, I asked a similar question about a certain class of polynomials that seem to defy the odds of "eventual divisibility", a property that is best explained by a slightly modified excerpt of the original question:

Look at the graph $G$ that is generated by the polynomial $q(x) = x^2+ax+b$ ($a,b \in \mathbb{Z}$) via the edge set $$\{(n, q(n) \text{ mod } p) : n =0,\ldots,p-1\}$$ for some prime $p \in \mathbb{P}$. After some thought, it should be clear that the statements $$``\text{Iterating } q \text{ for any input will always eventually lead to divisibility by some prime at least once.} ``$$ and $$``G \text{ has a path from any node to 0.}``$$ are equivalent. A polynomial $q$ with a prime $p$ has the property of "eventual divisibility" if one of these statements hold. Furthermore, "at least once" can be replaced by "periodically infinitely many times" and "every node has a path to $0$" can be characterized by "$G$ is weakly connected and has exactly one loop containing $0$".

After some careful case elimination, I was left with (i.e. could not prove/disprove the property for) three quadratic polynomials where linear and constant coefficients are absolutely smaller than $10$:

$(1)$ $x^2-7x-7$ (which is checked up to $p \leq 35800000$ by Mike Daas and me with no hits)

$(2)$ $x^2-7x+5$ (which is checked up to $p \leq 7100000$ by Mike Daas and me with no hits)

$(3)$ $x^2+5x+7$ (which was shown by Oscar Lanzi to be provably non-eventually divisible)

"No hits" just means that up to now this polynomial does not have a corresponding $p$ that gives it the "eventually divisible" property. Since the property seems to hold except for trivial exceptions (see other question), it seems highly unusual that these polynomials just happen to not have it by pure chance - even up in the millions as it turns out! The method that was used for $(3)$ can be applied similarly, but does not yield an exhaustive proof: Let's focus on $(2)$, since it has the smaller discriminant $\Delta = 29$. A key idea for disproving eventual divisibility is $$x^2-7x+5 \equiv 0 \mod p \text{ is not solvable} \iff \left(\frac{\Delta}{p}\right) = \left(\frac{29}{p}\right) = -1$$ Using quadratic reciprocity, we can figure out that $$\left(\frac{29}{p}\right) = \left(\frac{p}{29}\right) = -1 \iff p \equiv 2,3,8,10,11,12,14,15,17,18,19,21,26,27 \mod 29$$ i.e. $p$ congruent to one of these residues need not to be checked since the existence of a cycle at $0$ is disproven by the lack of solutions leading to $0$ when iterated. The same argument can also be applied to the fixed-point-method in the mentioned question, but the CRT guarantees that we will never cover all primes with this (and the discriminants get very, very big leading to extra casework). Thus, the list of $p$ left after this procedure begins $$p = 5,7,13,23,53,59,67,71,83,103,107,109,139,\ldots$$

For convenience, let's list the cycles present in the iteration graphs for each of these primes:

$$\begin{array}{c|c} p & \text{Cycles} \\ 5 & (0),(3) \\ 7 & (2),(6) \\ 13 & (0,5,8),(9,10) \\ 23 & (3,16,11) \\ 53 & (12),(16,43),(30,6,52,13) \\ 59 & (0,5,54,6,58,13,24),(14,44,40,27) \\ 67 & (15,58),(12,65,23,38,44,25,53,31) \\ 71 & (12,65),(48,56,51) \\ 83 & (33),(58),(36,53) \\ 103 & (48,16,46) \\ 109 & (20,47,32,42,58) \\ 139 & (21),(126),(85,102,104) \end{array}$$

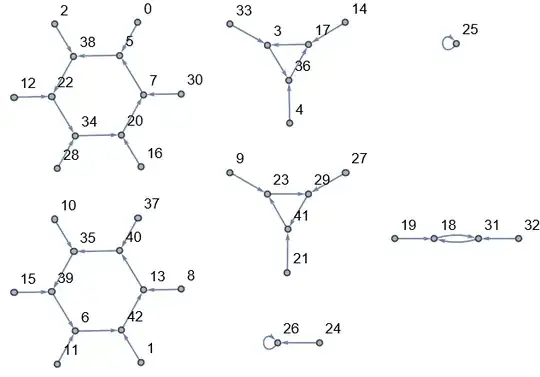

As a bonus, here is a quite bizarre pattern that I spotted while generating the graph for $x^2-7x+5$ with $p=43$:

I used Mathematica to generate this picture, to view different examples just change the parameters of the function:

PolyModGraph[poly_,var_,mod_] := Graph[Table[t \[DirectedEdge] Mod[poly/.x -> t,mod], {t,0,mod-1}], VertexLabels->"Name"];

PolyModGraph[x^2-7x+5,x,43]

There are many polynomial-prime combinations that show a $2$-fold, $3$-fold,... "rotational symmetry" of this kind, but there are also many that do not exhibit any symmetry at all.

The erratic behaviour of the cycle's lengths and their residue classes left me clueless and it does not spark much hope for a proof, but nonetheless:

Is it possible that the non-eventual divisibility of $x^2-7x-7$ and $x^2-7x+5$ happens to be just by chance, i.e. some anti-"strong law of small numbers" is at work here? Is there another way of proving this property besides the one given by Oscar Lanzi?