If any of the following exposition is unclear, please write a comment.

In essence, I am looking at the graph $G$ that is generated by the polynomial $q(x) = x^2+ax+b$ ($a,b \in \mathbb{Z}$) via the edge set $$\{(n, q(n) \text{ mod } p) : n =0,\ldots,p-1\}$$ for some prime $p \in \mathbb{P}$. After some thought, it should be clear that the statements $$``\text{Iterating } q \text{ for any input will always eventually lead to divisibility by some prime at least once.} ``$$ and $$``G \text{ has a path from any node to 0.}``$$ are equivalent. Furthermore, "at least once" can be replaced by "periodically infinitely many times" and "every node has a path to $0$" can be characterized by "$G$ is weakly connected and has exactly one loop containing $0$". With that out of the way, let's get to the question:

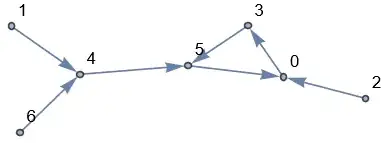

The natural question now is to know for which polynomials $q$ we have this nice property of "eventual divisibility" by some prime no matter what number we input, i.e. finding connected $G$ with a single loop containing $0$. This is not rare, see for example $q(x) = x^2+3$ for $p=7$:

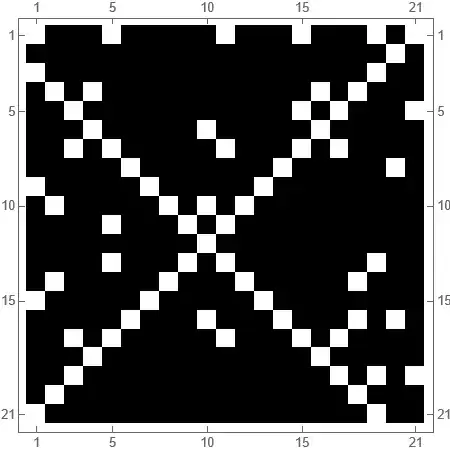

To get a feeling for how rare this is, let's look at the following plot:

This image displays, for $a = -10, \ldots, 10$ on the vertical axis and $b = -10, \ldots, 10$ on the horizontal axis, if $G$ has the aforementioned property for some $p < 113$ in black and otherwise white. There are some obvious cases like $a = b+2$ and $a = -b$ where this eventual divisibility will never occur since they have the one-cycles $(-1,-1)$ and $(1,1)$ respectively.

Modulo careful checking, we can eliminate quite a lot more trivial cases (i.e. explain white squares) in the diagram by searching for trivial one- and two-cycles, i.e. eventual divisibility seems to be the norm rather than the exception. In some other cases, eventual divisibility is found with a somewhat higher prime, such as $p=719$ for $x^2+5x+9$. Sparing you the details, we are left with the cases below, in which either eventual divisibility does not exist or it requires an especially large prime. The discriminant $\Delta$ is included if it helps:

- $x^2-10x-10$ (EDIT) is "eventually divisible" for every residue with $p = 11701$

- $x^2-10x-6$ (EDIT) is "eventually divisible" for every residue with $p = 31237$

- $x^2-10x+4$ (EDIT) is "eventually divisible" for every residue with $p = 6337$

- $x^2-10x+8$ (EDIT) is "eventually divisible" for every residue with $p = 13037$

- $x^2-7x-7$ checked for $p \leq 35800000$ by Mike Daas and me ($\Delta = 77$)

- $x^2-7x+5$ checked for $p \leq 7100000$ by Mike Daas ($\Delta = 29$)

- $x^2+5x+7$ is provably never "eventually divisible" as shown by Oscar Lanzi

- $x^2+3x+7$ (EDIT) is "eventually divisible" for every residue with $p = 225349$

Six of the eight cases above have been solved as indicated, but for the remaining two I cannot rule in or rule out this property. I know that this is a question about (pretty much hopelessly) chaotic behaviour, but perchance somebody has a thought or two on the following:

Since eventual divisibility seems to be occuring by pure chance every time, why do these exceptions stick out so much? Is there some anti-"strong law of small numbers" at work here? If so, are the heuristics that might suggest non-existence of such $G$ for given $q$?