Visualization

(based on Oscar's and Ed's answers)

Tetrahedral and cubic numbers are much easier to grasp than dodecahedral numbers.

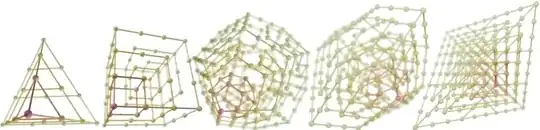

So, let’s build up 5 visualizations in parallel:

- Tetrahedral numbers

- Cubic numbers

- Dodecahedral numbers

- Dodecahedral' numbers (arranged halfway between a dodecahedron and tetrahedron)

- Dodecahedral'' numbers (arranged as a tetrahedron)

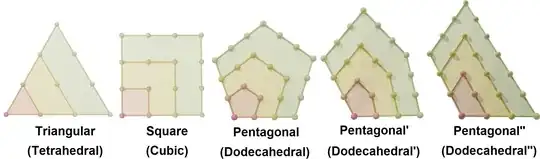

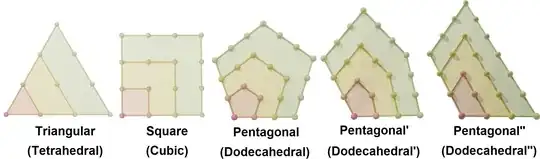

Here are the 2D equivalents. Each layer is drawn with a unique color. Notice how all layers share the red vertex:

Remove the intermediate points:

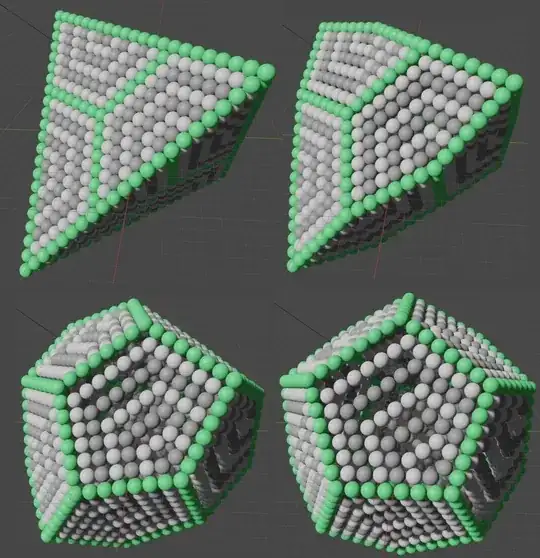

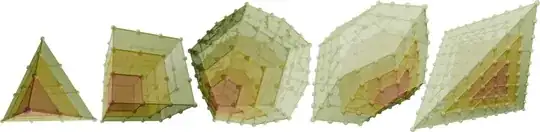

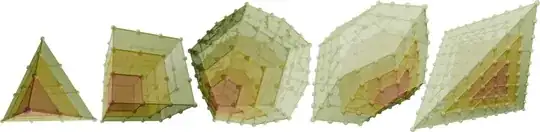

And extend to 3D. Again, each layer is a separate color. Note that 3 copies of the previous step share the red vertex. The rest of the faces are not shared among layers:

Add the intermediate points back in:

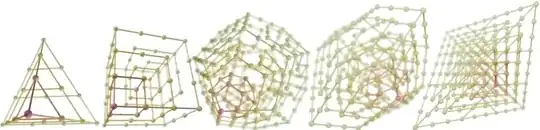

Remove the faces:

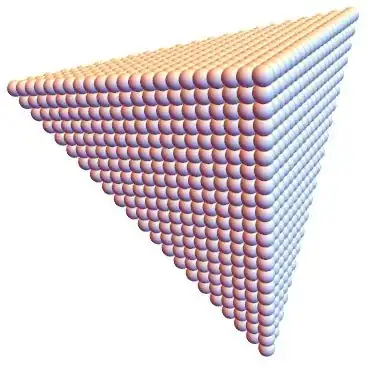

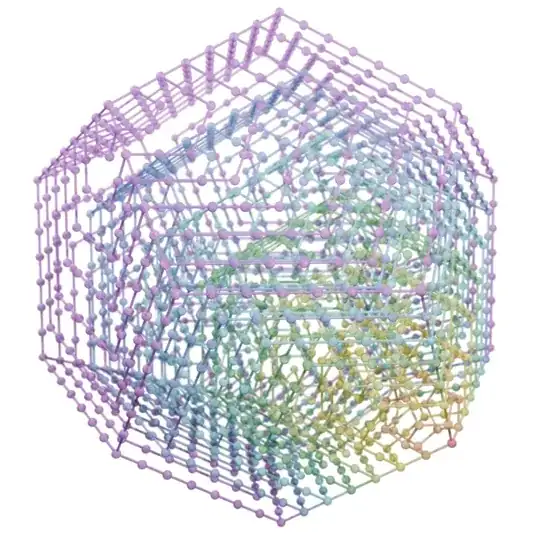

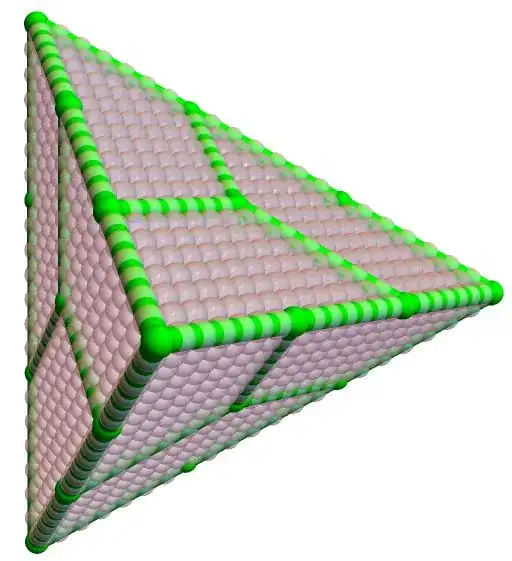

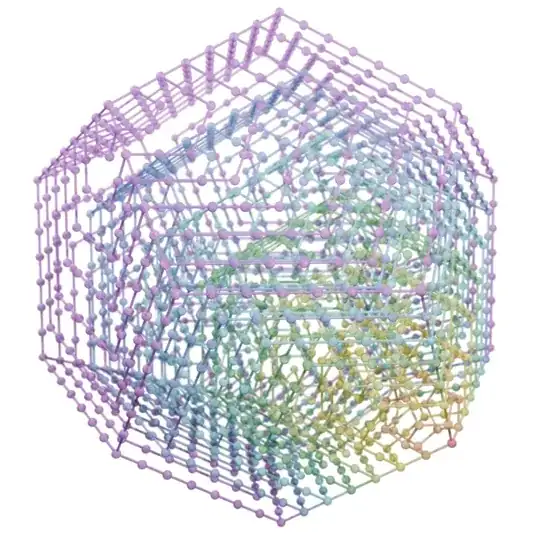

Here's the dodecahedral form with N=8 (2024 points):

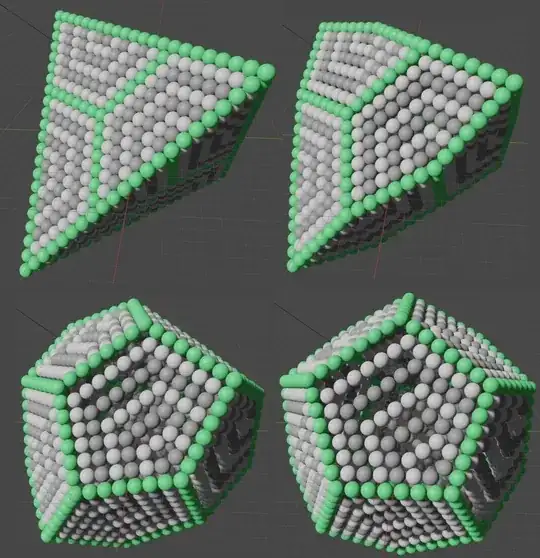

And the dodecahedral'' form, again with N=8 (2024 points):

Justification of dodecahedral numbers using tetrahedral form

(from Oscar)

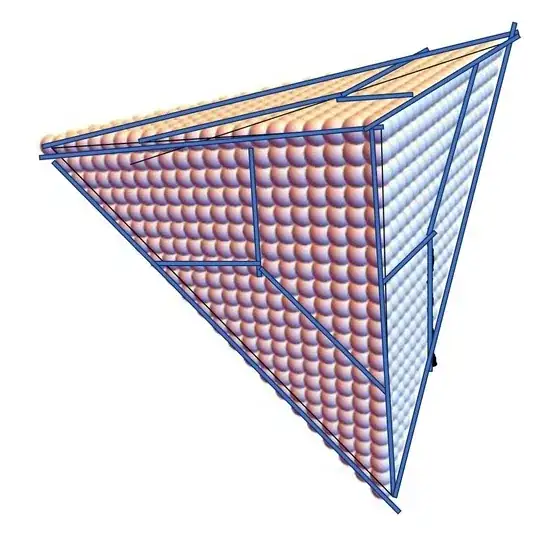

The idea is to divide each trapezoid into 3 triangles, and warp those triangles to form a pentagon. This works well for pentagonal numbers:

As with other figurate numbers, we may regard the array as being built from layers, or gnomons, surrounding one vertex of the figure, which we take to be the "origin". To understand how smaller dodecahedral numbers are embedded in larger ones, we first identify the proper gnomon. With the dodecahedral form at the end of this animation series, the gnomon is identified by selecting one vertex as the origin and the gnomon then consists of all the faces not touching this vertex, therefore nine dodecahedral faces. These faces have $18$ interior edges and ten interior vertices. Since the tetrahedral form has three dodecahedral faces for each tetrahedral face, the gnomon in the tetrahedral form becomes three tetrahedral faces with the origin now in the center of the fourth tetrahedral face. The face center will always have a ball on it when the tetrahedral-number argument is $3n+1$, which is the appropriate tetrahedral argument for a dodecahedral number.

In both forms we can calculate that the outer gnomon for $2024$ will have $694$ balls, which is what we would need for the eighth dodecahedral number ($2024$) to embed the next lower one ($1330$). With the dodecahedral form, the dodecahedral-number argument is $8$ and we count the number of balls in the gnomon as follows:

$(9×92)-(18×8)+10=694$

The first term is the eighth pentagonal number ($92$) on each of the nine gnomonic faces; but this double-counts the $18$ interior edges and triple-counts the ten interior vertices in the gnomon. Thus the second term removes the double-counted edges while the third term restores the triple-counted interior vertices (we think of the multiple-countings as a toggle switch).

In the tetrahedral form, the three-faced gnomon has $22$ balls on each edge, as the tetrahedral-number argument is $22$; and the calculation analogous to the one above gives

$(3×253)-(3×22)+1=694,$

where $253$ is the 22nd triangular number. With the proper number of balls in the outer gnomon thus verified ($2024-1330=694$ for this case), the dodecahedral numbers embed their predecessors in the same way as more familiar figurate numbers.

Old stuff

Here's an animation sequence based on Oscar's and Ed's answers: