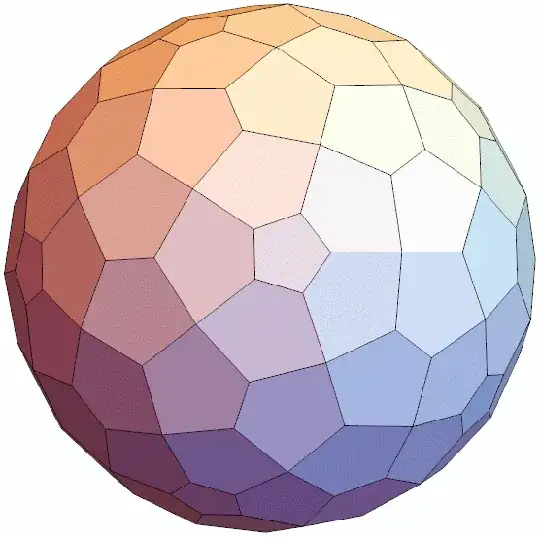

There is an easy way to get a polyhedron with $10n+2$ pentagons only.

Start with a regular dodecahedron. Take a congruent dodecahedron and merge it face to face with the first one, removing the merged faces to get an increment of $10$ faces. Repeat as desired with additional regular dodecahedra.

Yes, it's ugly, in that we lack convexity and don't have elegant symmetry (for $n \ge 2$). But it systematically makes infinitely many numbers of faces work, and the faces themselves are regular.

Addendum:

Following up on @Kundor's answer, we can interpret this in terms of graph theory. When we merge an additional dodecahedron into the figure, we are dividing one of the pentagonal faces of the graph into $11$ faces, such that the adjacent faces are undisturbed (they remain pentagonal). Such a division can be applied to any "base" ployhedron, so for example a base polyhedron with $16$ faces guarantees polyhedra with $10n+6$ faces, $n\ge 2$, as well.

Combining this result with @Kundor's implies that almost any even number of faces $\ge 12$ can be accessed. Only $14$ and $18$, which are not multiples of $4$ and too small to be reached via the $10$-face incrementation, require further analysis. For $18$ we have a planar graph corresponding to a polyhedron (basically a trigonal bipyramid where each face is divided in thirds) but for $14$ there are no planar graphs and thus no solutions!*

So the possible numbers of faces turn out to be $12$ and all even numbers greater than or equal to $16$.

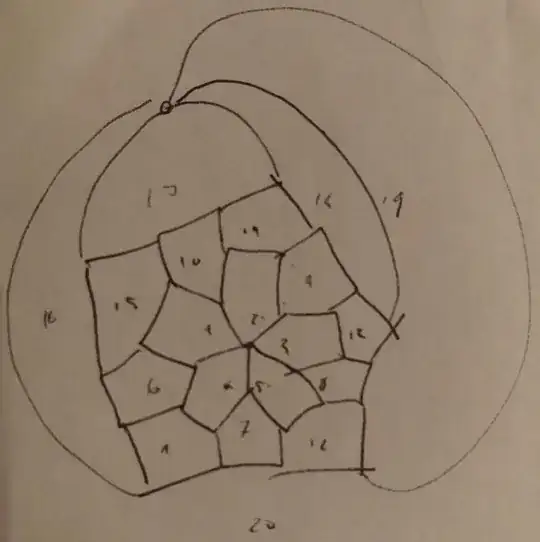

*We prove the lack of a pentagonal 14-hedron by a pigeonhole argument. First observe that there must be $5×14/2=35$ edges, therefore from the Euler characteristic 23 vertices. The sum of all orders of these vertices is $2×35=70=(3×23)+1$, meaning there must be one order-4 vertex out of the 23, the rest being order-3.

Now draw the order-4 verrex. It is surrounded by four faces which together take up 16 of the edges and twelve additional vertices. Eight of the additional vertices must have another edge emerging from it, thus accounting for a total of 24 edges and 12 faces. The remaider of the polyhedron, closing up the "bottom" side, must have two faces supplying 11 additional edges — but the faces are pentagonal and thus can supply a maximum of only ten more edges. $\rightarrow\leftarrow$

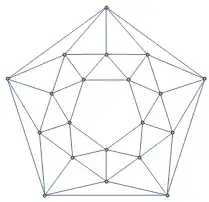

With 16 pentagonal faces the closure would have four faces and 16 edges, which is possible by constructing the second order-4 vertex existing in that case. This is Nick Matteo's construction.