A straight line can be drawn with a straightedge.

A circle can be drawn with a compass.

An ellipse can be drawn with string and pins.

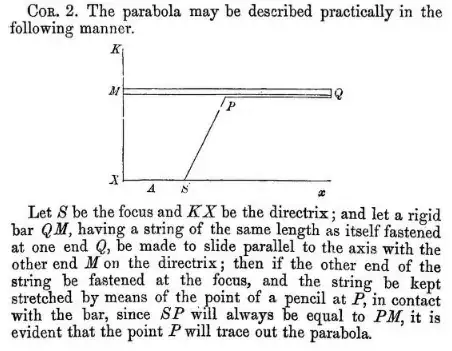

How can we draw a parabola, using basic equipment?

Remarks

The parabola should be "perfect" (like a circle drawn with a compass), not just a rough sketch. As far as how much of the parabola should be shown: enough so that it looks like a "U".

We can use basic equipment such as string, pins, etc. The simpler the equipment, the better (so for example, a method using an unmarked straightedge is better than a method using a marked straightedge). High tech tools like computers are not allowed. You are given paper, pen and a flat table.

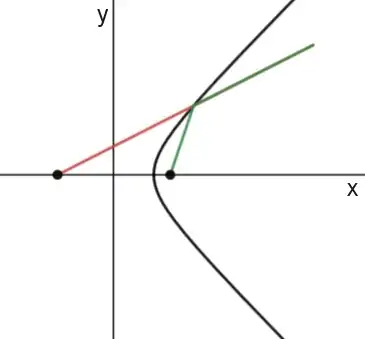

We can define a parabola as the set of points in a plane equidistant to a fixed line (directrix) and a fixed point (focus), or use any equivalent definition.

I tried to find how the ancient Greeks physically drew parabolas, but found nothing.

Students at my school made an almost-perfect parabola using strings and pins, by setting strings such that for each string the sum of its $x$- and $y$- intercepts is $30$, so the strings are tangent to an envelope curve $\sqrt x + \sqrt y = \sqrt{30}$, which is a rotated parabola.

But this is not quite what I'm looking for, because it's not quite perfect, as the number of strings is finite.

In this video a carpenter shows how to make a beautiful almost-perfect parabola, similar to the string art above, but again it's not quite perfect because the number of lines is finite.

If it's not possible to draw a perfect parabola using basic equipment, then is there an explanation?