I have gained a comprehension of the operational process through the discussion located at Why does Newton's method work?. Nevertheless, there is one aspect that remains unclear to me.

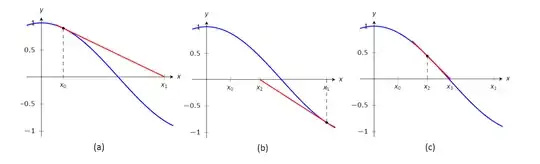

To initiate, we choose a pair of values, $(x_0, f(x_0))$, where $x_0$ is in proximity to the true root of $f(x)$ that I am seeking. Subsequently, we determine the linearization of $f(x)$ at this point, denoted as $L_{x0}(x)$. In favorable conditions, I can identify the root of $L_{x0}(x)$, which I will refer to as $x_1$. It seems reasonable to anticipate that $x_1$ will provide a more accurate approximation to the true root of $f(x)$, which is the one I actually require.

However, I am uncertain about how creating a tangent line at the point $(x_1, f(x_1))$ will result in a more precise approximation, which we can designate as $x_2$, to the true root of $f(x)$ in comparison to $x_1$.

My explanation is that, for the same reason $x_1$ provided a superior approximation to the true root of $f(x)$ compared to $x_0$, $x_2$ offers a better approximation than $x_1$. Nonetheless, I am still unsure about my own response and remain open to any clarifications or insights on this matter.