In this answer, we

prove that $\frac{G(n, f)}{n} \to \frac{\mathbf{E}[X]^2}{\mathbf{E}[X^2]} $ whenever $\mathbf{E}[X] < \infty$, and

show that $G(n, f)$ converges to some constant for some distribution $f$.

The statement and proof of each of the above claims will be demonstrated below, but let me make some informal remarks first.

The asymptotic behavior of $G(n, f)$ is determined by the survival function $R(t) = \mathbf{P}(X > t)$, which measures how much the distribution of $X$ is heavy-tailed. Indeed, $G(n, f)$ grows more slowly when $f$ is more heavy-tailed (or $R(t)$ decays more slowly). A heuristic computation shows:

If $R(t)$ decays fast enough so that $\mathbf{E}[X^2] < \infty$, then $G(n,f) \asymp n$.

If $R(t) \asymp t^{-2}$, then $G(n, f) \asymp (\log n)^2$.

If $R(t) \asymp t^{-(1+\alpha)} $ for some $0 < \alpha < 1$, then $G(n, f)$ converges.

In my answer, both Claim 1 and a special case of Claim 3 is proved. If you are interested, I will try to hack the other cases and/or generalize the claims.

Part 1. Assume $\mathbf{P}(X > 0) = 1$ and $\mathbf{E}[X] < \infty$. Then

$$ \frac{G(n, f)}{n} = \mathbf{E}\Biggl[ \frac{\left( \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} X_i \right)^2}{\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_i^2} \Biggr]. $$

Either by Cauchy–Schwarz inequality or Jensen's inequality, we find that

$$ 0 \leq \frac{\left( \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} X_i \right)^2}{\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_i^2} \leq 1. $$

Moreover, by the strong law of large numbers,1)

$$ \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} X_i \to \mathbf{E}[X] \in (0, \infty)

\qquad\text{and}\qquad

\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} X_i^2 \to \mathbf{E}[X^2] \in (0, \infty] $$

almost surely as $n\to\infty$. So by the dominated convergence theorem,

$$ \lim_{n\to\infty} \frac{G(n, f)}{n}

= \mathbf{E}\Biggl[ \lim_{n\to\infty} \frac{\left( \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} X_i \right)^2}{\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_i^2} \Biggr]

= \frac{\mathbf{E}[X]^2}{\mathbf{E}[X^2]}. $$

Part 2. The main claim of this part is as follow:

Theorem. In the case $f$ is the Pareto distribution,

$$ f_{X_i}(x) = f(x) = \frac{\alpha}{x^{\alpha+1}} \mathbf{1}_{\{x > 1\}}, $$

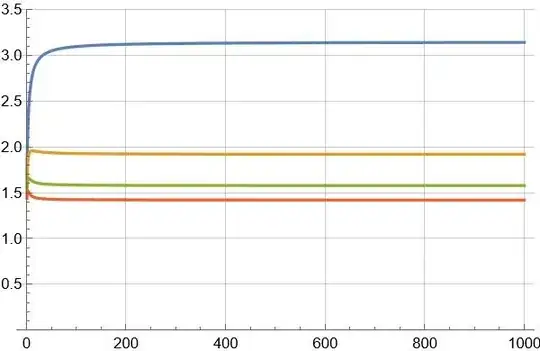

where $0 < \alpha < 1$, the quantity $G(n, f)$ converges:

$$ \bbox[color:navy; padding:8px; border:1px dotted navy;]{ \lim_{n\to\infty} G(n, f) = 1 + \frac{\alpha \Gamma (\frac{1-\alpha}{2})^2}{2 \Gamma(1-\frac{\alpha}{2})^2}. } \label{main_res}\tag{$\diamond$} $$

Our starting point is @River Li's excellent represention,

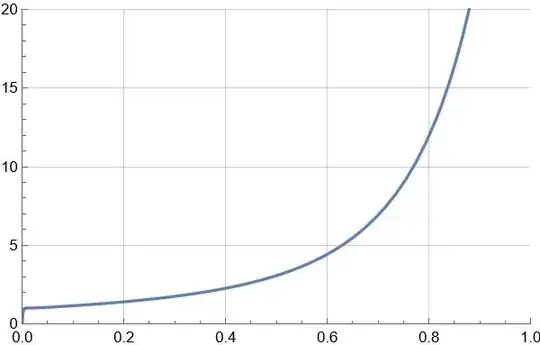

$$ G(n, f) = 1 + n(n-1) \int_{0}^{\infty} A_0(t)^{n-2}A_1(t)^2 \, \mathrm{d}t, \label{G}\tag{1} $$

where $A_k(t) = \mathbf{E}[X^k e^{-t X^2}]$. Using \eqref{G}, we examine a class of probability distributions and show that the corresponding $G(n, f)$ converges to a finite value as $n \to \infty$.

We first obtain an integral representation of $A_k(t)$. Substituting $y = tx^2$,

\begin{align*}

A_k(t)

= \int_{1}^{\infty} \frac{\alpha}{x^{\alpha+1-k}} e^{-tx^2} \, \mathrm{d}x

= \frac{\alpha}{2} t^{(\alpha-k)/2} \int_{t}^{\infty} \frac{e^{-y}}{y^{(\alpha+2-k)/2}} \, \mathrm{d}y.

\end{align*}

From this, we make several observations about $A_0(t)$ and $A_1(t)$.

1. For $k \in \{0, 1\}$, we have

\begin{align*}

A_k(t)

\leq \frac{\alpha}{2} t^{(\alpha-k)/2} \int_{t}^{\infty} \frac{e^{-y}}{t^{(\alpha+2-k)/2}} \, \mathrm{d}y

= \frac{\alpha}{2t} e^{-t}. \label{bound:Ak}\tag{2}

\end{align*}

2. When $k = 0$, set $c_0 := \frac{\alpha}{2} \int_{0}^{\infty} \frac{1 - e^{-y}}{y^{(\alpha+2)/2}} \, \mathrm{d}y \in (0, \infty)$. Then by using $A_0(0) = 1$, we get

\begin{align*}

A_0(t)

&= 1 + A_0(t) - A_0(0) \\

&= 1 - \frac{\alpha}{2} t^{\alpha/2} \int_{t}^{\infty} \frac{1 - e^{-y}}{y^{(\alpha+2)/2}} \, \mathrm{d}y \\

&= 1 - c_0 t^{\alpha/2} + \frac{\alpha}{2} t^{\alpha/2} \int_{0}^{t} \frac{1 - e^{-y}}{y^{(\alpha+2)/2}} \, \mathrm{d}y.

\end{align*}

Since $1 - e^{-y} \leq y$, this gives

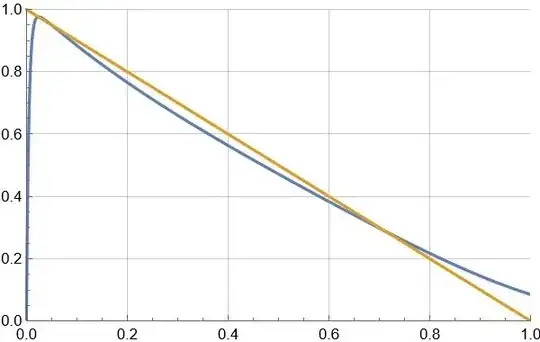

$$ 1 - c_0 t^{\alpha/2} \leq A_0(t) \leq 1 - c_0 t^{\alpha/2} + \frac{\alpha}{2 - \alpha} t \label{bound:A0_1}\tag{3} $$

Also, when $t \in (0, 1]$ and with $c_0' := \frac{\alpha}{2} \int_{1}^{\infty} \frac{1 - e^{-y}}{y^{(\alpha+2)/2}} \, \mathrm{d}y \in (0, \infty)$, it follows that

$$ A_0(t) \leq 1 - c_0' t^{\alpha/2} \leq \exp\left( - c_0' t^{\alpha/2} \right). \label{bound:A0_2}\tag{4} $$

3. When $k = 1$, we have $c_1 := \frac{\alpha}{2} \int_{0}^{\infty} \frac{e^{-y}}{y^{(\alpha+1)/2}} \, \mathrm{d}y \in (0, \infty)$. Hence,

\begin{align*}

A_1(t)

&= \frac{c_1}{t^{(1-\alpha)/2}} - \frac{\alpha/2}{t^{(1-\alpha)/2}} \int_{0}^{t} \frac{e^{-y}}{y^{(\alpha+1)/2}} \, \mathrm{d}y

\end{align*}

From this, it follows that

$$ \frac{c_1}{t^{(1-\alpha)/2}} - \frac{\alpha}{1-\alpha} \leq A_1(t) \leq \frac{c_1}{t^{(1-\alpha)/2}}. \label{bound:A1}\tag{5} $$

Now we return to analyzing the asymptotic behavior of $G(n, f)$ as $n\to\infty$. To make use of \eqref{G}, we introduce two auxiliary quantities:

\begin{align*}

I_n &= n(n-1) \int_{0}^{1} A_0(t)^{n-2}A_1(t)^2 \, \mathrm{d}t, \\

J_n &= n(n-1) \int_{1}^{\infty} A_0(t)^{n-2}A_1(t)^2 \, \mathrm{d}t.

\end{align*}

By invoking \eqref{bound:Ak}, we get

\begin{align*}

J_n

\leq n^2 \int_{1}^{\infty} \left( \frac{\alpha}{2t} e^{-t} \right)^{n} \, \mathrm{d}t

\leq n^2 \left( \frac{\alpha}{2e} \right)^{n}.

\end{align*}

This shows that $J_n \to 0$ exponentially fast. Next, we turn to estimating $I_n$. Plugging \eqref{bound:A1} into $I_n$,

\begin{align*}

I_n

&= n(n-1) \int_{0}^{1} A_0(t)^{n-2} \left( \frac{c_1}{t^{(1-\alpha)/2}} + \mathcal{O}(1) \right)^{2} \, \mathrm{d}t \\

&= c_1^2 n(n-1) \int_{0}^{1} \frac{1}{t^{1-\alpha}} A_0(t)^{n-2} \left( 1 + \mathcal{O}(t^{(1-\alpha)/2}) \right)^{2} \, \mathrm{d}t.

\end{align*}

Substituting $c_0 t^{\alpha/2} = s/n$, or equivalently $t = (s/c_0 n)^{2/\alpha}$,

\begin{align*}

I_n

&= \frac{2 c_1^2 (1 - n^{-1}) }{\alpha c_0^2} \int_{0}^{c_0 n} s A_0\left(\frac{s^{2/\alpha}}{(c_0n)^{2/\alpha}} \right)^{n-2} \left( 1 + \mathcal{O}\Bigl( \frac{s^{(1-\alpha)/\alpha}}{n^{(1-\alpha)/\alpha}} \Bigr) \right)^{2} \, \mathrm{d}s.

\end{align*}

Moreover, as $n \to \infty$,

the bound \eqref{bound:A0_2} shows that $A_0\left(\frac{s^{2/\alpha}}{(c_0n)^{2/\alpha}} \right)^{n-2}$ is bounded by an exponential function, and

the estimate \eqref{bound:A0_1} shows that $A_0\left(\frac{s^{2/\alpha}}{(c_0n)^{2/\alpha}} \right)^{n-2} \to e^{-s}$ pointwise.

So by the dominated convergence theorem, we get

$$ I_n

\to \frac{2 c_1^2 }{\alpha c_0^2} \int_{0}^{\infty} se^{-s} \, \mathrm{d}s

= \frac{2 c_1^2 }{\alpha c_0^2}. $$

Moreover, it is not hard to check that $ c_0 = \Gamma(1-\frac{\alpha}{2}) $ and $ c_1 = \frac{\alpha}{2} \Gamma(\frac{1-\alpha}{2}) $. Therefore the desired conclusion \eqref{main_res} follows.

Below Python code computes an approximate value of $G(10^4)$ for $\alpha = \frac{1}{2}$ through Monte Carlo simulation using $10^6$ samples:

import numpy as np

def gen_sample(n):

x = np.random.rand(n) ** (-2)

return (np.sum(x) ** 2) / np.sum(x ** 2)

data = [gen_sample(10000) for _ in range(1000000)]

The exact value of lim G(n) is 3.188439615...

np.mean(data)

I got $3.1866881493312955$, which is reasonably close to the value $1+\frac{\Gamma (1/4)^2}{4 \Gamma (3/4)^2} = 3.188439615...$ we obtained from \eqref{main_res}.

Footnotes.

1) SLLN works whenever the expectation exists in the extended real number line $[-\infty, \infty]$.

$n$" />

$n$" />