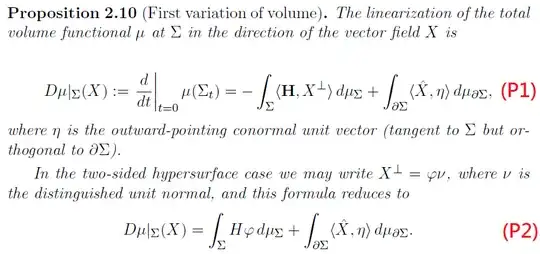

Fix a closed hypersurface $\Sigma$ in a Riemannian $3$-manifold $(M,g)$. Let $\Sigma_t$ be a family of closed hypersurfaces evolving from $\Sigma$ by inverse mean curvature flow (IMCF) in $M$. That is, given $x\in\Sigma$, they obey $$\frac{d}{dt}\Phi_t(x)=-\frac{\mathbf{H}}{H^2}=\frac{1}{H}\nu,\tag{D}$$ where $\mathbf{H}$ is the mean curvature vector of $\Sigma_t$ and $\Phi_{t\in(-\epsilon,\epsilon)}:M\to M$ is a one-parameter family of diffeomorphisms such that $\Phi_0$ is the identity map and $\Phi_t(\Sigma)=\Sigma_t$. If $d\mu_{\Sigma_t}$ denotes the Riemannian volume form on $\Sigma_t$, I would like to show that $$\frac{\partial}{\partial t}d\mu_{\Sigma_t}=d\mu_{\Sigma_t}.\tag{1}$$ This formula is included in Geometric Relativity by Dan A. Lee, and he says that it can be inferred from Proposition 2.10, which reads:

The $X$ here is a vector field on $M$ defined by $$X(p)=\frac{d}{dt}|_{t=0}\Phi_t(p),$$ and that $\hat{X}$ is the tangential part of $X$ obtained from the decomposition relative to the unit normal vector field $\nu$.

Idea: Since we are talking about the hypersurface case with $X$ being purely normal, I would opt for (P2) with vanishing $\hat{X}$, which gives me $$\frac{d}{dt}|_{t=0}\mu(\Sigma_t)=\int_\Sigma H\varphi d\mu_\Sigma=\int_\Sigma d\mu_\Sigma=(\text{the area of $\Sigma$}).\tag{2}$$ This is still far from the desired equation (1). As a matter of fact, I don't even know how the author ditched that particular time instant $t=0$. Could somebody tell me what else he might have done to translate (2) into (1)? Thank you.

Added: Maybe I missed something important. The author said Proposition 2.10 tells us that for any $t$, $$\frac{d}{dt}(\Phi_t^*d\mu_{\Sigma_t})=\Phi_t^*(\mathrm{div}_{\Sigma_t}X_t)(\Phi_t^*d\mu_{\Sigma_t}),$$ where $X_t$ is defined by $$X_t(\Phi_t(p))=\frac{d}{dt}\Phi_t(p),$$ but I don't see how this works.