Recently, I've started studying path signatures and, currently, I'm reading a standard reference, namely "A Primer on the Signature Method in Machine Learning" by Ilya Chevyrev and Andrey Kormilitzin. Now, at some point the authors try to show how path signatures naturally emerge in the theory of Controlled Differential Equations, and they do so via Picard iterations. So far, so good. The things that are bothering me are the following:

The authors claim that a map $V: \mathbb{R}^e \to L(\mathbb{R}^d,\mathbb{R}^e)$ can be equivalently seen as a map $V: \mathbb{R}^d \to L(\mathbb{R}^e,\mathbb{R}^e)$. This I am more or less willing to accept. Indeed, if we consider $x \in \mathbb{R}^d$ and $y \in \mathbb{R}^e$, we observe that $$ y \in \mathbb{R}^e \mapsto V(y) \in \mathbb{R}^{e \times d} \implies V(y)x \in \mathbb{R}^e, $$ yields a map in $\mathcal{L}(\mathbb{R}^e, \mathbb{R}^e)$ by taking $y$ to $V(y)x$ for all $y\in \mathbb{R}^e$. If we now consider this map to be parameterized by $x$, we end up with a map $\mathbb{R}^d \to \mathcal{L}(\mathbb{R}^e, \mathbb{R}^e)$ associated to $V$. This association can be made one-to-one, thus we may equivalently treat $V$ as a linear map $\mathbb{R}^d \to \mathcal{L}(\mathbb{R}^e, \mathbb{R}^e)$. I think this is what the authors had in mind, but I'd appreciate more insight.

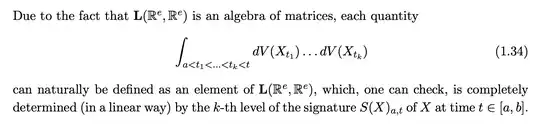

Now, my main problem is the claim made in the beginning of page 10. They say:

Here $X$ is a path $[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}^d$ and $Y$ is another path $[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}^e$. How do signatures actually pop out of this iterated integral? Is it just by the linearity of $V$ and the integral? I want to see something of the form $$\int_{a<t_k<b} \int_{a<t_{k-1} < t_k} ... \int_{a < t_1 <t_2} dX_{t_1}^{i_1} ... dX_{t_{k-1}}^{i_{k-1}} dX_{t_k}^{i_k}$$ Could you help me figure out how to formally derive the iterated integral above from the quantity (1.34)?