The proofs given in the answers to Equivalent definition $\text{Cone}(K)$ and Cones over noncompact spaces are not unions of paths are more general, but let us follow Dugundji's advice.

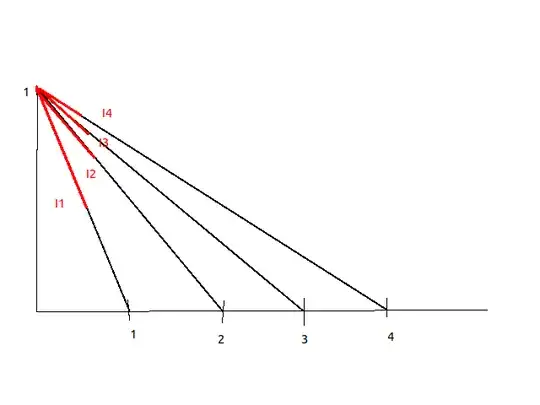

First let us note that Dugundji is imprecise when he claims that the spaces $CX$ and $TX$ are not homeomorphic. What he really means becomes clear if we look at his sketch: There is a canonical map $f' : X \times I \to TX$ given by $f'(x_n,t) = tw_0 + (1-t)x_n$. Here $x_n = (n,0)$. Since $f'(X \times \{1\}) = \{w_0\}$, we get a continuous bijection

$$f : CX \to TX .$$

Dugundji means that $f$ is not a homeomorphism, otherwise his sketch does not make any sense.

Dugundji defines $V_n = \{ y \in L(x_n, w_0) \mid \lVert w_0 - y \rVert < 1/n \}$, where $L(a,b)$ is the line segment connecting $a, b \in \mathbb R^2$. Writing $y = tw_0 + (1-t)x_n$ we get $y \in V_n$ iff

$$\lVert w_0 - tw_0 - (1-t)x_n \rVert = \lVert (1-t_n)(w_0 - x_n) \rVert = (1-t_n)\lVert w_0 -x_n \rVert < 1/n ,$$

i.e. $t > t_n :=1 - 1/n\lVert w_0 -x_n \rVert$. Of course $V = \bigcup_n V_n$ is not a subset of $CX$, so Dugundji certainly means that $V$ is not open in $TX$, but $f^{-1}(V)$ is open in $CX$.

- $V$ is not open in $TX$.

If it were open, then it would contain some set $TX \cap B(w_0;r)$ with $r > 0$. Hence for each $n$ the set $V_n$ would contain all $y \in L(x_n,w_0)$ with $\lVert w_0 - y \rVert < r$. But this is false for $1/n < r$.

- $f^{-1}(V)$ is open in $CX$.

Let $p : X \times I \to CX$ denote the quotient map. The set $W = \bigcup_n \{ x_n \} \times (t_n,1]$ is open in $X \times I$ because $X$ is discrete, thus $V = p(W)$ is open in $CX$ since $p^{-1}(p(W)) = W$. But clearly $f^{-1}(V) = p(W)$.

Remark:

If we want to show that $CX$ and $TX$ are not homeomorphic, we cannot pick a special map and show that it is no homeomorphism. We need some additional argument. A general result was proved in the above two links.

Here is a variant adapted to the present case.

Assume that there exists a homeomorphism $h : CX \to TX$. Let $*$ denote the tip of $CX$ given by $\{ * \} = p(X \times \{1\})$.

We must have $h(*) = w_0$. In fact, since $CX \setminus \{*\}$ has infinitely many path components. Thus $TX \setminus \{y\}$ must have infinitely many path components for $y = h(*)$. The only point with this property is $y = w_0$. We conclude that $h$ maps each "line segment" $L'(x_n) = p(\{x_n\} \times I)$ homeomorphically onto some $L(x_{\phi(n)},w_0)$, where $\phi : \mathbb N \to \mathbb N$ is a bijection.

The above set $V$ is not open in $TX$, but we can easily show as above that $h^{-1}(V)$ is open in $CX$.