The mistake is that orthonormal bases come in two opposite orientations, called left handed and right handed. Undoubtedly you remember from high school physics that $\vec{u}$, $\vec{v}$ and $\vec{u}\times\vec{v}$ typically form a right handed set (in that order). Thumb, index finger, middle finger and all that. The division exists in all dimensions though we typically first hear about in 3D. In the current context $R$ is a change of bases matrix. The matrix $R$ takes one orthonormal basis to another if and only if $R^{-1}=R^T$, whence $\det R=\pm1$. If $\det R=+1$, then it takes a right-handed orthonormal basis to another right-handed system. But if $\det R=-1$, then the handedness is reversed.

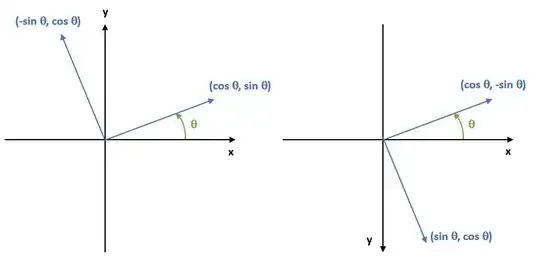

Look at your image. Place the thumb of your right hand along the original $x$-axis, and the index finger along the $y$-axis. Your middle finger will point towards you (from the screen). If you do the same with the other two vectors, you notice that the middle finger will point away. The handedness is reverse, and that shows in the determinant.

Handedness can be fixed by replacing one of the orthonormal vectors $\vec{v}$ with the opposite vector $-\vec{v}$. Or by permuting any two vectors. More generally, odd permutations of basis vectors change the handedness while even permutations keep it.

One more remark. The space itself has no preferred handedness (at least not mathematically, particle physicists may disagree). Therefore it is somewhat incorrect to call a basis right-handed without specifying a reference basis. In 3D, once you have drawn $\vec{i},\vec{j},\vec{k}$, you have given a reference basis, and we can use the determinant, as above, to check whether some other orthonormal basis shares the same orientation or not.