Long comment. I believe this type of question is extremely hard, if not impossible by the current technology, to answer. However, let me share some observation.

Define $\varphi_n$ by the $n$th sum:

$$ \varphi_n(x) = \frac{n}{2} + \sum_{k=0}^{n} \cos(2^k x) $$

We will consider the behavior of $\varphi_n (x)$ near $x = \frac{2\pi}{3}$.

\begin{align*}

\varphi_n\left(\frac{2\pi}{3} + (-1)^n \frac{x}{2^n} \right)

&= \frac{n}{2} + \sum_{k=0}^{n} \cos\left(\frac{2^{k+1}\pi}{3} + (-1)^n \frac{x}{2^{n-k}}\right) \\

&= \frac{n}{2} + \sum_{k=0}^{n} \left[ -\frac{1}{2}\cos\left(\frac{x}{2^{n-k}}\right) + (-1)^{n-k+1}\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\sin\left(\frac{x}{2^{n-k}}\right) \right] \\

&= -\frac{1}{2} + \sum_{k=0}^{n} \left[ \sin^2\left(\frac{x}{2^{n-k+1}}\right) + (-1)^{n-k+1}\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\sin\left(\frac{x}{2^{n-k}}\right) \right] \\

&= -\frac{1}{2} + \sum_{j=0}^{n} \left[ \sin^2\left(\frac{x}{2^{j+1}}\right) + (-1)^{j+1}\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\sin\left(\frac{x}{2^{j}}\right) \right] \\

&= -\frac{1}{2} + 2 \sum_{j=0}^{n} \sin\left(\frac{x}{2^{j+1}}\right)\sin\left(\frac{x}{2^{j+1}}+(-1)^{j+1}\frac{\pi}{3}\right).

\end{align*}

Using this, define $\psi(x)$ by

$$ \psi(x) = -\frac{1}{2} + 2 \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} \sin\left(\frac{x}{2^{j+1}}\right)\sin\left(\frac{x}{2^{j+1}}+(-1)^{j+1}\frac{\pi}{3}\right). $$

Since $\varphi_n \bigl( \frac{2\pi}{3} + (-1)^n \frac{x}{2^n} \bigr)$ converges locally uniformly to $\psi(x)$ on $\mathbb{R}$, it follows that

$$\inf_{x\in\mathbb{R}} \psi(x) \geq \limsup_{n\to\infty} \left( \min_{x\in\mathbb{R}} \varphi_n(x) \right). $$

A numerical calculation suggests that $L = \inf \psi$ with an approximate value

$$\inf \psi \approx -0.70399210451640656752$$

at $x \approx 0.66123108104874561312$. Unfortunately, all the inverse symbolic calculators I tried could not identify this value. My gut is also telling that $L$ has no elementary closed-form, but again, this is rather a bold claim.

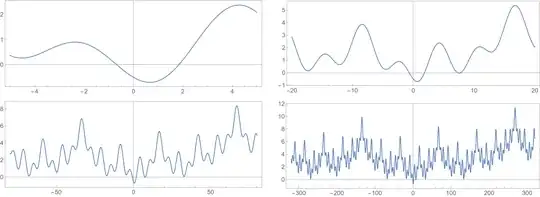

For fun, I included the graph of $\psi$: