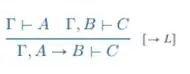

The $(\to \text L)$ rule uses two upper sequents: one with the $A$ to the right of the $⊢$ sign and one with $B$ to the left of the $⊢$ sign to introduce the $A → B$ formula to the left of the $⊢$ sign in the lower sequent.

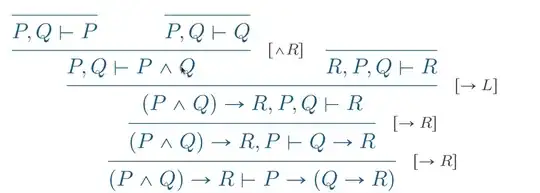

The rule is applied above with $P,Q \vdash (P \land Q)$ as the upper left sequent: $\Gamma \vdash A$, where:

$\Gamma = \{ P,Q \}$ and $(P \land Q)$ is $A$,

and $R,P,Q \vdash R$ as upper right sequent, where:

$\Gamma = \{ P,Q \}$ and $R$ is $B$.

Why it works?

Intuitively, the sequent $\Gamma \vdash A$ reads: "from $\Gamma$, $A$ follows", and sequent $\Gamma, B \vdash C$ reads "from $\Gamma$ and $B$, $C$ follows".

Thus, writing them in tree-form (like Natural Deduction) this is like Conditional Elimination (aka: Modus Ponens).

Maybe it helps to consider the semantics of sequents; see Gaisi Takeuti, Proof Theory (2nd ed - 1987), page 9:

intuitively a sequent $\gamma_1, \ldots, \gamma_m \vdash \delta_1, \ldots, \delta_n$ means :

"if $\gamma_1 \land \ldots \land \gamma_m$, then $\delta_1 \lor \ldots \lor \delta_n$".

Obviously, we want that the rules of the calculus are sound, i.e. that when the upper sequents are true, also the lower one is.

By contraposition, consider the case when the lower sequent $\Gamma, A \to B \vdash C$ is false: we have to show that at least one of the upper sequents is false.

Discarding for simplicity the context $\Gamma$, this happens when $A \to B$ is true and $C$ is false.

Assume now that both upper sequents are true; the fact that $C$ is false implies that also $B$ is false. But now we have $A \to B$ true and $B$ false, that means that also $A$ is false, contradicting the assumption that the left upper sequent is true.

Similar for $(\to \text R)$: $\dfrac {\Gamma, A \vdash B}{\Gamma \vdash A \to B}$ that corresponds obviously to Conditional Introduction.