The following problem is from the appendix to chapter 12, "Parametric Representation of Curves", in Spivak's Calculus

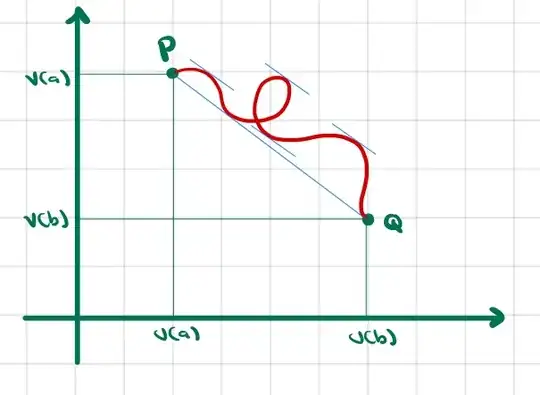

- Let $u$ and $v$ be continuous on $[a,b]$ and differentiable on $(a,b)$; then $u$ and $v$ give a parametric representation of a curve from $P=(u(a),v(a))$ to $Q=(u(b),v(b))$. Geometrically, it seems clear (see figure below) that at some point on the curve the tangent line is parallel to the line segment from $P$ to $Q$. Prove this analytically. Hint: This problem will give a geometric interpretation for one of the theorems in Chapter 11. You will also need to assume that we don't have $u'(x)=v'(x)=0$ for any $x \in (a,b)$.

Proof

Assuming $u(b) \neq u(a)$, the line segment from $Q$ to $P$ has a parametric representation

$$(w(t),z(t))=\left (t,v(a)+\frac{v(b)-v(a)}{u(b)-u(a)}(u(t)-u(a)) \right), t \in [a,b] \tag{1}$$

Let $d(t)=v(t)-z(t)$.

Then $d(a)=0$ and $d(b)=0$.

Since $d$ is differentiable on $(a,b)$, we can use Rolle's Theorem

$$\exists c, c \in (a,b) \land d'(c)=0$$

The derivative of $d$ at $c$ is

$$d'(c)=v'(c)-z'(c)=v'(c)-u'(c)\frac{v(b)-v(a)}{u(b)-u(a)}=0$$

$$v'(c)(u(b)-u(a))=u'(c)(v(b)-v(a))\tag{2}$$

$(2)$ looks like the result of the Cauchy Mean Value Theorem. However, the geometric interpretation hasn't come up yet I believe.

We'd like to be able to divide everything by $u'(c)$, which would give us

$$\frac{v'(c)}{u'(c)}=\frac{v(b)-v(a)}{u(b)-u(a)}\tag{3}$$

The left-hand side can be shown to be the slope of the tangent at at $(u(c),v(c))$, the right-hand side is the slope between $Q$ and $P$. Is this is the geometric interpretation of Cauchy Mean Value Theorem, namely, that given a parametric (vector-valued) function, and two points, there is some point with parameter value in between the two points' parameter values such that the slope of the parametric curve equals the slope between the two points?

But can we divide everything by $u'(c)$?

Suppose $u'(c)=0$, what does this mean? $(2)$ implies that since $u(b)\neq u(a)$ then $v'(c)=0$

My question is how do we interpret a situation in which both $u'(c)$ and $v'(c)$ are zero?

Moving on to complete the proof, if we assume $u'(c)\neq 0$ then we can divide and obtain $(3)$. But why did the problem say we'd have to assume that $v'(c)$ is also $\neq 0$?