This question is a follow-up to this question about a problem in Spivak's Calculus.

Given differentiable functions $u$ and $v$ defined below, points $P=(u(a),u(b))$ and $Q=(v(a),v(b))$, and a parametric curve $c(t)=(u(t),v(t)), t\in [a,b]$ from $P$ to $Q$, I'd like to investigate if and when there is some point on the curve between $P$ and $Q$ such that the tangent has the same slope as the slope between $P$ and $Q$.

As shown in the linked question, this issue is linked to the Cauchy Mean Value Theorem.

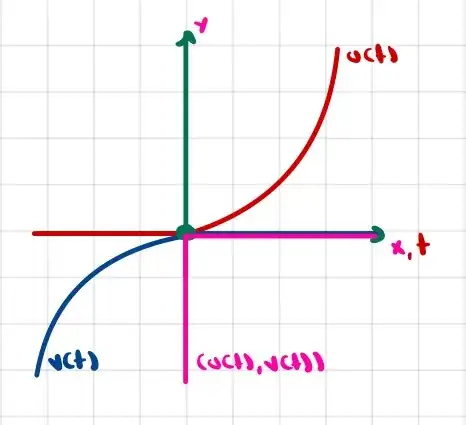

Consider the functions $u,v: [-1,1] \to \mathbb{R}$, defined by

$$u(x)=\begin{cases} 0; &x<0 \\ x^2; &x\geq 0,\end{cases}\quad v(x)=\begin{cases}-x^2;&x< 0\\0;&x\geq 0.\end{cases}$$

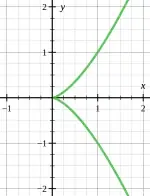

Here is a depiction of the parametric curve $c(t)=(u(t),v(t))$ in pink:

To cut to the chase, here is my question

$v'(0)$ and $u'(0)$ are differentiable, and we can differentiate $c(t)$ by differentiating each component function, yet the curve represented by $c(t)$ doesn't seem to be differentiable at $t=0$, where there is a kink. What is the name for this sort of situation and what theorems tell us more about it? I just finished a chapter on Parametric Representation of Curves in Spivak, and the only comment I recall about this situation is that it doesn't make sense to define the tangent line as $c(a)+sc'(a)$ at such a point $a$ where $u'(a)$ and $v'(a)$ are both zero. Does this mean there is never a tangent line at points like this?

Here is the context in which this question came up for me

Let $a$ and $b$ in $[-1,1]$.

Case 1: $a<b$ in $[0,1]$

The curve is $(t^2,0)$ for $t \in [0,1]$. This corresponds to $y=0$ for $x \geq 0$.

The slope between any two points is always the same, $0$.

If we apply the Cauchy Mean Value Theorem to $(a,b)$, we obtain

$$[u(b)-u(a)]v'(c)=[v(b)-v(a)]u'(c)\tag{1}$$

for $c \in (a,b)$.

Since, for $t \in [0,1]$ we have $v'(t)=0$, and $v(t_1)=v(t_2)$ for any $t_1$ and $t_2$ in $[0,1]$, equation $(1)$ is true.

Note that we can divide by $u'(c)$ in $(1)$ to obtain

$$\frac{v'(c)}{u'(c)}=\frac{v(b)-v(a)}{u(b)-u(a)}=0$$

which says that the slope $y'(x)$ of the parametric curve at $c$ equals the slope between the curve evaluated at $a$ and $b$.

Case 2: $a<b$ in $[-1,0]$.

The curve is $(0,-t^2)$ for $t \in [-1,0]$. This corresponds to $x=0$ for $y \leq 0$.

The slope between any two distinct points in $[-1,0]$ is either $\infty$ or $-\infty$.

Since $u'(t)=0$, and $u(t_1)=u(t_2)$ for any $t_1$ and $t_2$ in $[-1,0]$, equation $(1)$ of Cauchy's Mean Value Theorem is again true.

Note that we can divide by $v'(c)$ to obtain

$$\frac{u'(c)}{v'(c)}=\frac{u(b)-u(a)}{v(b)-v(a)}=0$$

which says that the slope $x'(y)$ of the parametric curve at $c$ equals the slope between the curve evaluated at $a$ and $b$.

Case 3: $a<b, a \in [-1,0), b \in (0,1]$

This is the special case and more interesting case.

From the graph above, we can see that the curve has a kink at $(0,0)$. Both $u'(0)$ and $v'(0)$ are $0$.

I've been studying parametric equations, and I just realized that I am not sure I know how to tell if a curve represented by a parametric equation is differentiable. Each component function is differentiable, but it seems the parametric function is not. What is the relevant theorem that deals with this issue?

Anyways, from a visual inspection it seems that given $a$ and $b$, there is no $c$ in between them such that the slope of the curve at $c$ is the same as the slope between the curve at $a$ and the curve at $b$.

However, equation $(1)$ still seems to be true if $c=0$, because $u'(0)=v'(0)=0$.