Say I have a symmetric matrix that lives in $xy$ space. I will write it as $$A = \begin{pmatrix} a & b \\ b & c \end{pmatrix}.$$ I am interested in the covariance matrix, so let me also say $a,c>0$, and $A$ is positive-definite, which means $|b|\leq\sqrt{ac}$. The eigenvalues of $A$ are therefore $\geq 0$, and the eigenvectors are orthogonal. The eigenvalue problem $A\mathbf{x}=\lambda\mathbf{x}$ reads $$\begin{pmatrix} a & b \\ b & c \end{pmatrix}\begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix} = \lambda \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix}.$$ The system of equations can be written as \begin{cases} y = x(\lambda-a)/b \\ x = y(\lambda-c)/b, \end{cases} and combined to yield $$ \frac{c-a}{b}=\frac{y}{x}-\frac{x}{y}.$$

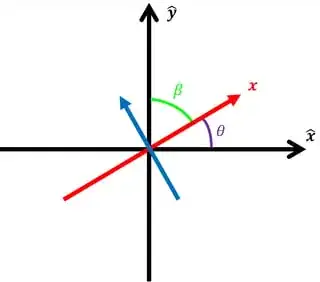

In the figure above, the red and blue vectors are the eigenvectors with the larger and smaller eigenvalue respectively. Working with the largest one, I can write the equation above the figure as \begin{align} \frac{c-a}{b} &= \tan{\theta}-\tan{\beta} \\ &= (1+\tan{\theta}\tan{\beta})\tan(\theta-\beta) \\ &= 2\tan(2\theta-\pi/2) \\ &=-2\cot(2\theta), \end{align} where to write the second equality I have used the trigonometric identity for the tangent of a difference. The third line follows from writing $\tan \theta \tan \beta = 1$ and $\beta = \pi/2 - \theta$. Lastly, I used the trigonometric relations between complementary angles to write the last equality, which can be recasted as \begin{equation} \tan(2\theta) = \frac{2b}{a -c}. \end{equation}

The following equation $$\theta = \frac{1}{2}\textrm{atan2}(2b,a-c),$$ where $\textrm{atan2}(y,x)=\textrm{Arg}(x+iy)$, can be used to compute the angle the eigenvector with largest eigenvalue, $\mathbf{x}$, makes with the $x$-direction. Choosing the principal branch, the range of $\theta$ is $(-90,90]^\circ$, i.e. the right half of the plane.

PROBLEM

As you may have noticed, I absorbed the eigenvalue $\lambda$ in the equation right before the figure. This means the rest of the derivation should hold for both eigenvectors of $A$. However, I have tested the calculation with multiple cases and magically the angle which $\theta$ measures is always that between the $x$-direction and the eigenvector with largest eigenvalue.

As an example, we can look at the special case $$A = \begin{pmatrix} a & 0 \\ 0 & c \end{pmatrix},$$ where the eigenvectors are aligned with the coordinate axes, and $a$ and $c$ are the eigenvalues.

If $a>c$, we get $\theta=0^\circ$. However, if $a < c$, we get $\theta = 90^\circ$.

Can anybody provide me with an explanation of why the ambiguity in the eigenvector that $\theta$ is describing seems to fade away somehow? I'd really appreciate it!

NEW OBSERVATION

I have realised something interesting. If I multiply $$\tan(2\theta) = \frac{2b}{a -c}$$ by $-1$ twice, getting $$ \tan(2\theta) = \frac{-2b}{c-a},$$ and I proceed as before and write $$\theta = \frac{1}{2}\textrm{atan2}(-2b,c-a),$$ now the angle is calculated between the $x$-axis and the eigenvector with the smaller eigenvalue!

In the wikipedia article on $\textrm{atan2}$, specifically the section called "East-counterclockwise, north-clockwise and south-clockwise conventions, etc.", it says:

Apparently, changing the sign of the x- and/or y-arguments and swapping their positions can create 8 possible variations of the $\mathrm{atan2}$ function and they, interestingly, correspond to 8 possible definitions of the angle, namely, clockwise or counterclockwise starting from each of the 4 cardinal directions, north, east, south and west.

I think this brings me closer to the answer to my question but I need some help putting everything together.

VISUAL AID

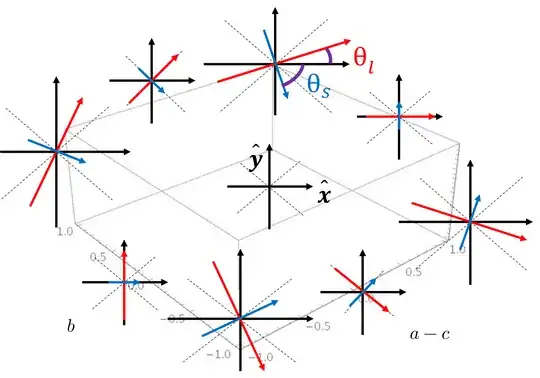

Let me call the eigenvectors with larger and smaller eigenvalue $\mathbf{L}$ and $\mathbf{S}$ respectively. Let's look at how a few eigenvectors might look like in the $(a-c,b)$ plane. Consider the sketch that follows. The eigenvectors $\mathbf{L}$ and $\mathbf{S}$ are drawn in red and blue respectively, and the angle they make with the $x$ axis is called $\theta_l$ and $\theta_s$ respectively in the top subplot. As you can see, traversing the $(a-c,b)$ plane clockwise leads to the direction of the eigenvectors in the $xy$ plane rotating clockwise too. The arrow heads indicate the side of the vectors which falls in the range $(-90,90]^\circ$.

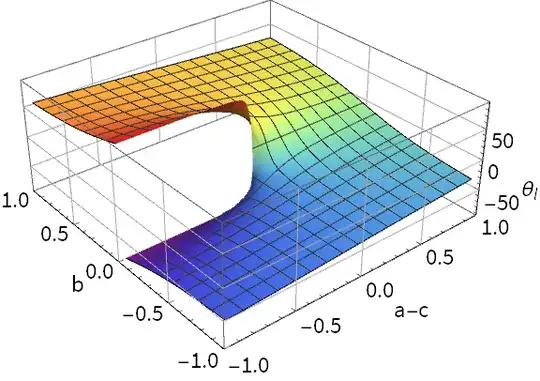

I have used Mathematica to produce the following surface plots of the angles in the $(a-c,b)$ plane. This is how the angle between the $x$ axis and $\mathbf{L}$, given by $$\theta_l=\frac{1}{2}\textrm{atan2}(2b,a-c),$$ looks like:

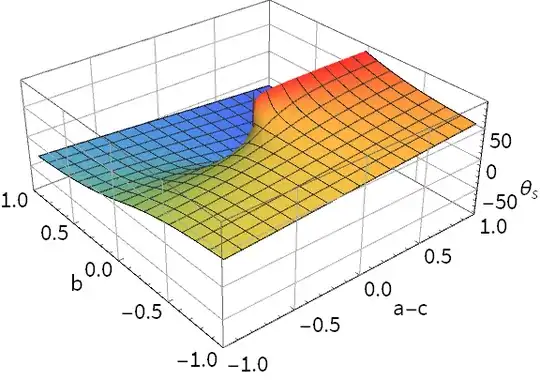

And this is how the angle the $x$ axis makes with $\mathbf{S}$, $$\theta_s=\frac{1}{2}\textrm{atan2}(-2b,c-a),$$ looks like:

If you check the surface values you can see they match what my sketch described.

Let's come back to what was described in the wikipedia link.

- We can see $\textrm{atan2}(y,x)$ follows the "East-anticlockwise" convention. We have $\theta_l=0^\circ$ when $\mathbf{L}$ is pointing East, and the angle grows as $\mathbf{L}$ rotates anticlockwise.

- Now, if we try to make sense of the $\theta_s$ values as if they described $\mathbf{L}$ too, we can see $\theta_s=0^\circ$ when $\mathbf{L}$ is pointing North, and grows as $\mathbf{L}$ rotates anticlockwise. Hence, the $\textrm{atan2}(-y,-x)$ convention might be "North-anticlockwise".

But again, I don't know what is special about $\mathbf{L}$. From the derivation of the angles, either equation could have corresponded to either eigenvector. There is still a missing piece of the puzzle which I believe must lie in the derivation of the equation for $\theta_l$. Can anybody give me a hand? Any insights would be greatly appreciated.

SUMMARY

The equation $$\tan(2\theta) = \frac{2b}{a -c}$$ holds for the azimuths of both eigenvectors, L and S, of the matrix $$A = \begin{pmatrix} a & b \\ b & c \end{pmatrix}.$$

Let me define 2 new vectors:

- $\mathbf{p}=(a-c,2b)$, with azimuth $\gamma_p=\textrm{atan2}(p_y,p_x)$.

- $\mathbf{n}=-\mathbf{p}$, with azimuth $\gamma_n=\textrm{atan2}(-p_y,-p_x)$.

We can write $$\tan(2\theta) = \tan(\gamma_p) = \tan(\gamma_n).$$

It turns out using the first equality we get $$2\theta_l=\gamma_p=\textrm{atan2}(2b,a-c),$$ where $\theta_l$ is the angle between the $x$ axis and the eigenvector with larger eigenvalue, $\mathbf{L}$.

The second equality $$2\theta_s = \gamma_n = \textrm{atan2}(-2b,c-a)$$ gives us $\theta_s$, the angle between the $x$ axis and the eigenvector with smaller eigenvalue, $\mathbf{S}$.

Now the question remaining is why does that happen? How could I have predicted that $\mathbf{p}$ and $\mathbf{n}$ would always have an azimuth that is twice that of $\mathbf{L}$ and $\mathbf{S}$ respectively?

DIAGONALISATION

I have found this derivation from Howard E. Haber from his Physics 116A class of Winter 2011. He obtains the same equation for $\tan(2\theta)$ by diagonalising the matrix $A$ (note the difference in notation: he uses $b$ in $A_{22}$, and $c$ in the off-diagonal terms). He then proceeds by setting constraints in the angle $\theta$. When he plugs his eq. 1 in his eq. 8 he makes it explicit that $\theta$ is measuring the angle between the positive $x$ axis and the eigenvector with largest eigenvalue. The conclusions drawn are the same as mine, but I somehow bypassed all that when I decided to use the function atan2 (unjustifiably, but it works). The question remains: why does my approach of using atan2 work?